The Questions That Reveal If A New Hire Will Succeed

October 01, 2025

Hosted By

Dan Sullivan

Dan Sullivan

Jeffrey Madoff

Jeffrey Madoff

Curious questions change everything, especially when hiring and building teams. Dan Sullivan and Jeffrey Madoff swap stories about how great conversations reveal true fit and why creating space for engagement and originality beats chasing predictability every time. Discover why the best teams are cast for creativity and growth, not just to fill a role.

Show Notes:

What makes a good conversationalist is what makes a good salesperson—curiosity that invites a real exchange.

The best salespeople don’t pitch; they ask questions that spark new thinking.

If candidates show up knowing the company and armed with questions, they instantly set themselves apart.

When people engage with you and the moment, they tend to show up fully in everything they do.

Seeing an owner enjoying their work is the best advertisement for joining a team.

If you’re hiring for predictability, you’re going to structure things in such a way that unpredictability can’t happen.

The best test for any team member: Would you hire them again, knowing everything you know now?

Context matters—people shine brightest when the environment is right for their talents.

Leadership happens where new capabilities are created, not from job titles or louder voices.

Resources:

Learn about Strategic Coach®

Learn about Jeffrey Madoff

Casting Not Hiring by Dan Sullivan and Jeffrey Madoff

Always Be The Buyer by Dan Sullivan

The Talent Delusion by Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic

Growing Great Leadership by Dan Sullivan

Episode Transcript

Jeffrey Madoff: This is Jeffrey Madoff, and welcome to our podcast called Anything and Everything with my partner, Dan Sullivan.

Dan Sullivan: We were just talking, Jeff, about hiring because we're writing the book, Casting Not Hiring. And from your experience, because you've had companies for 50 years, what have you learned to do that seems always to work? And over the past, what have you sort of eliminated that really doesn't work from the standpoint of bringing new people into your team?

Jeffrey Madoff: You know, I haven't reflected on that. Good question, because one of the things that I did just instinctually is whatever person I was considering, if I liked them, first of all, I would have my executive producer, Ed Daly, who was with me 20-some years. If he didn't like them, I didn't need to meet them, you know? And I imagine in a way that's like you and Babs. If one of you doesn't like them, It's kind of done, you know, there's no point. But if he does, and then I interview them and like them, and then I say to them, there's, you know, eight other people here, I'm going to introduce you and you sit and talk and ask them whatever questions you want. And they'll ask you questions, just have a conversation, just get a feel for the place. And I don't think we ever made a bad hiring decision doing that. Earlier on in one of my first companies, which actually had a lot more people just because of the nature of the work. In production, it's lots of freelance subcontractors that you use. When I had the clothing company, it was different because I had sales staff in New York and I had people around the country on the road and all kinds of different things and contractors and all of that couldn't do this sort of thing. And a lot of these people never had contact with the other people and so on. But I remember when I was interviewing salespeople, I thought, God, this guy's an aggressive enough asshole. Maybe he's a good salesman. And they were a lot of talk, but they weren't good salespeople. At that time, I was in my 20s, and I didn't know quite how to assess that because I hate being sold to. So that was inherent dissonance. It would happen. But if I enjoyed talking to you and you engaged me, you sold me, you know? But if you were telling me how great you are, you didn't have any questions, you know, or anything like that, that would turn me off. And so there are a lot of the aggressive salespeople who weren't very good at all. but I thought they might be, and I was trying to second guess my instincts based on what I liked and didn't like, but once it really settled in, I realized, like anything else, selling is a relationship, and a good selling means you can sell that person more than once because you've established trust and you've built a relationship. And learning that was a thing.

Dan Sullivan: You know, more and more as I go along, it might be the nature of our business and it may be the nature of what we're essentially selling in the marketplace. But my sense is what makes a good conversationalist also makes a good salesperson. And what I mean is a good conversationalist will ask questions. They don't just respond, they ask questions. Okay. And I think a good salesperson, we have a book, one of our small books, it's called Always Be the Buyer. And I talked to our sales team. We have about 14 worldwide. We have 14 who are working every day to bring new entrepreneurs into Strategic Coach. And I say, you know, what you have to find out is if this person is actually right for us. It's not a question of whether we're right for them. We have enough of a reputation. We have enough in the marketplace that the reason why you're talking to the person is because he's heard or she's heard about the program. But the question is, is this the sort of person that we want to have come into the program? If you were finding that out, what kind of questions would you ask the person to find out whether they're the right person or not? And some of the salespeople, the whole concept that they as a salesperson should be asking the other person questions just strikes them as very foreign, and they don't last. The salespeople don't last. I said, how can you do the matching up between them if you're not asking them questions? I mean, they may be looking for a totally different kind of program. We're not the program for them. And you would get them in, you know, let's say there's enough momentum in their mind that they're really interested, they really want to be part of this program, but this isn't what they're looking for. So they'll come in and they'll be dissatisfied, you know. Anyway, but… I think the whole notion of selling is going through a profound change in today's world because we're used to being hit. We're used to being, you know, 3,000 times a day, a billboard, a sign is hitting us, but none of them are really asking us questions.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, because, you know, the technology that came up within the last 15 years or so has allowed that two way communication as opposed to the seller, essentially dictating the terms of discussion by what they tell you, you know, and so I think you're right. Ultimately, I think it's the same in the sense that you're trying to close a sale.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: But the interaction that I think one is looking for is different because I think that it's really interesting, you know, now with streaming, you have to pay more to not have commercials. That tells you something.

Dan Sullivan: Number one, well, there's a value that you would pay for.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, I mean, there's a value paid for in terms of the not being interrupted by commercials.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: But it's, you know, kind of funny because initially it's like mosquitoes. Yeah, pay to get rid of them. You know, as they call it, pest control. But I think it's interesting. I was just thinking about this the other night, because we're watching a series and these commercials came in. And you can't fast forward through them. You have to buy an additional tier of service and pay about twice as much to not have commercials. So doesn't that tell you that there is something inherently annoying about most commercials? And it used to be also between the Oscars and the Super Bowl, that's when the big new campaigns and that, you know, they tried to make us think that was news in itself. that there was this new Apple commercial or new whatever, and they were paying $8 million for 30 seconds on the Super Bowl. But when you have the different streaming services now, all of them have their either paid or not paid. And it's gone back to what was happening in the 50s when everybody was afraid of cable because they said that's the beginning of paid television. and really pay television is what's happening now. And you can pay us and we won't assault you with commercials. I mean, there's something inherently fascinating.

Dan Sullivan: I think so. Yeah. And I've just been noticing because I, you know, I mean, my life has really been based on, you know, even in childhood, I really wasn't interested in other children until age six, there weren't any other children in my life. And I was curious, you know, and I was responsive. So I had to practice on adults. And I would ask them, you know, were you in World War I? What was going on when World War I was going on? I was born in Second World War, so you were asking 30 or 40-year-olds, you know, what was going on in their life. And it's interesting that So a job applicant comes in and they ask questions, or they've really studied what the company's about before they walk in. They're in another league. They're in a totally other league. I mean, they've just differentiated themselves from everybody just instantly by being interested to find out what the company is all about, but then to have some questions in their mind, you know, where do you see the company going? You know, are you expanding sales and everything like that? These are very simple questions, but it shows they have some business sense, too, you know, that not necessarily me, but if they're talking to someone who's, you know, in the leadership role and thinking, you know, is the company expanding? You know, is it getting bigger? You know, is it getting better? You know, I mean, that's a fairly important question, you know, if you're going to devote your life eight hours a day to working someplace.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, in a way, it's like dating, you know, if you're out with somebody for the first time, and you only talk about yourself. They're waiting for that to be over. You know, so the mere fact that you're also showing interest in somebody else, in what they're doing, and why do you think this is the right fit for you? What is it about we're doing that resonates with you? Where would you like to be in a few years? And there are people that clearly have read some bad books, and their answer is, well, in a few years, I wanna be in your position. I'll be in this company. Wrong answer. Yes. And then I have been interviewed where, you know, people say, so what is a question that, you know, I could ask you about something that you are embarrassed about that you would never tell anybody else? Why would I tell you that? Makes no sense. Why would I tell you that? Well, are there questions that you find annoying? I said, yeah, like that one.

Dan Sullivan: These are psych majors.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I mean, these are people that somehow think they've cornered the market.

Dan Sullivan: Or they've got tricks, they've learned tricks.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, they think. But the point is that if that trick is effective on you, I wouldn't want you working in my company. They spill the beans way too easy.

Dan Sullivan: I guess one of the qualities we're zeroing in on here is engagement. Are they someone who engages? Exactly. They engage. If they engage with you, they engage with the situation that they're in, they'll probably engage with other situations.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, well, if you're a person that is curious enough to even ask questions, do you have any questions? No, no, not really. Have you seen our work? No. I said, have you been to our website? No, I haven't had a chance to, but if you could show me some of the things. I said, why did you show up for this interview? You don't know what we do. You haven't even looked at our website. What could possibly be interesting to you about us? You don't know anything about us. Why would you want to work here? And then you get this silence because they weren't expected to be asked that kind of question. And I'm thinking, you're not doing yourself a service, you know, by that. So, Do you know Netflix's Keeper Test? So this is interesting. It's a method used by managers to assess employee retention. And it revolves around the question, if this person wanted to leave, would I fight to keep them? Which is an interesting question. There was, well, I'll ask you that question first. Have you ever been in that situation? Which role are you asking me about? I'm asking you about if this person wanted to leave, would you want to fight to keep them?

Dan Sullivan: I never have, but we do a pretty good job on a continual basing of asking people how they want to grow in the company. At least quarterly, everybody gets a chance to expand. what they would like to be doing. So if they've gone through that process for years, two years, three years, and they wanna leave, my feeling is that they're looking for something else and they're not finding it with us. And we're very supportive. We're very supportive. Now, if they're using it as a negotiating tactic, they've chosen the wrong tactic. Right.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, there was a woman that I interviewed liked her a lot. Ed liked her a lot, myself and the producer. I liked her a lot. And so this was on a Thursday. And I said, you know, we already have some other interviews, but I'm very, very interested in you. We're going to wrap this up tomorrow. I'll let you know Monday morning. But if anything were to happen before then with you, please let me know because I'm genuinely interested. And I liked her a lot. Really smart. very good. And she called me on Friday afternoon and said, Well, I wanted to tell you I've accepted another job. And I said, Is it something that you liked more? Or you know, what was the reason? And she said, honestly, I can't afford to not know. It makes me too uncomfortable, too anxious. And so I wanted to take something that was a for sure offer. And I said, I understand that. Have you signed any agreement with them? She said, no. And I said, I will pay you more than they're paying you. And I'll commit to you now. And she was like, really? And I said, yeah, I think you're that good. And I like you. And I wanted to be courteous to the other people we had scheduled. But if this is the case, I don't have to look any further. And anyhow, she came on board, was with me for two and a half, three years. We are still good friends, get together for dinner. And she was somebody that I considered that fighting to keep her, although I didn't even have her yet. And I did not think she was negotiating. I believed her answer. I had somebody else. I was in a situation where I had to let somebody go. And then the person who he had reported to, I was letting her go, and he came in and handed me a letter. And I said, what's this? And he said, well, I want Chris's job. And I said, you want me to open this letter? And he said, yes, this is what I want. And he thought that I was in a vulnerable enough position because I lost that person that I couldn't stand to lose him too. And I said, so you want that job, is that correct? And he said, yes. And I said, I don't think that you're there yet. And he goes, well, that's my ultimatum. And I said, and another thing which you haven't learned about me is I don't respond to ultimatums in a favorable way. So no, you don't have the job and you just lost the one you had because I will not be thinking about somebody who waits for me to be in a vulnerable position to then make demands. And that was the end of that. So I'll also fight to get rid of somebody if I think they're going to be negative to the company.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, it's part of the issue there. I'm just thinking about this person you're doing. They haven't fully committed to anything. That's the big problem. They want someone else to create the opportunity. I mean, if you got a promotion on the base of an ultimatum, all trust in the situation is gone. Yeah. Yes. And why would I want to keep… And neither of you like seeing each other every day. Right.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. No, that's true. That's true. So with that first question, if this person wanted to leave, would I fight to keep them? Another one of their keeper tests.

Dan Sullivan: But that person, you didn't actually have her. You know what I mean? It's that you wanted to keep the possibility that she could be there. She wasn't actually with you. So I think it's a modification on the keeper strategy.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I mean, I think the keeper strategy, the Netflix test needs some kind of context because if the person wants to leave because, you know, I hate your guts, I hate what the company does, I'm not going to fight to keep you. You know, if it's something like in her case where she needed the certainty to know that she could pay her expenses and, you know, she needed to be working. I understand that. And that didn't make me feel like there was anything. I wanted her because I thought she was that good and she was. She was wonderful. So another interesting question I think is, knowing everything I know today, would I hire this person again? We've done that. How so? Explain that.

Dan Sullivan: Well, it usually comes up around promotions, okay, where there's a promotion. And I said, well, it's not a question, would we promote him? It's a question is if knowing what we know about how he's performed so far, would we even hire him? Yeah, would we even hire him? Promotion is not in the works at all, but he's just reminded you that maybe you should rethink what's happened up until now, you know, and it's a dangerous policy on their part if they know that it's not going real well and they want a promotion. Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. And they're trying to force the issue. You know, one of the things really interesting, it's really hard for someone to fire themselves from a job. And what I mean by that, you know, it's not working and they know it's not working, but it's hard for them to be the person who initiates the activity to leave. OK. You know, it's really hard, first of all, because there's some legal and there's some financial issues to being fired rather than resigning. Right. Yeah. So, I mean, there's a complexity there that you have to take into consideration. But I don't have any problem firing people. I've probably fired about five or six because I'm not in a position. And the team that I have tend to stay, you know, for long periods of time. But I have no problem because Two people are trapped, really, when you have someone who's not performing. Two people are trapped. You're trapped and they're trapped. You know, as the person who owns the company, you're the person who has the ability to take action to solve it.

Jeffrey Madoff: And, you know… I was going to say that you're right, but I would also say that the problem goes beyond just the two of you. It's how does that negativity impact on the rest of the, in our case, ensemble.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, but I think the thing is the ensemble already knows. Oftentimes it's the owner doesn't know, you know, in other words, that, you know, I mean, we've had people and we fired and afterwards people came up and said, boy, I was hoping you would do that. I said, well, you didn't say anything. They says, it's hard to say, you know, it's, you're trashing somebody else in the company and everything like that. So, but I think it's one of the things that comes with ownership of the company. that you should have enough alertness and curiosity to find out who's actually doing well and who isn't doing well. And you don't have to do a focus group to find out.

Jeffrey Madoff: No, I agree. And so Netflix believes that it's best for both the employee and the company to part ways, often with a generous severance package. They can certainly afford that. And this test is part of their dream team, as they call it, their dream team philosophy. which is they aim to have only top performing individuals in every role. And the idea is to create a high performance environment where employees are constantly being challenged and encouraged to be their best. And if an employee is not a keeper, it's considered fair to all parties to allow them to pursue opportunities where they might be a better fit. which I think it's interesting and valid to a point. I think those questions are good to ask. Would I hire this person again? I think that's a really good question to ask. But it's also really interesting because in your company, in my company, in all companies, heavy, high turnover is not a good thing. And, you know, modeling my parents' behavior, people would say, you know, to my mom or to my dad, say, well, how do I get hired by the Madoffs? It seems like somebody has to die or leave. And, you know, both my parents were quite proud of that because they had so little turnover because people actually enjoyed seeing their colleagues at work and all of that. And I kind of picked up the same thing, that working together ought to be fun. We spend most of our waking hours doing this sort of thing. So it ought to be good.

Dan Sullivan: Of course, the obvious answer to that is if you die, we won't hire you. That's right. And if you leave, we won't hire you.

Jeffrey Madoff: And of course, the problem is if you die and I can't tell the difference.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. You know, it's kind of interesting. Remember Emily Post? Sure. Yeah. And Emily Post, you know, her book was about that thick. It covered all social situations. When was she? 30s, 40s, 50s? Something like that. I mean, she was… I think the 40s for sure, the 50s. Yeah. Yeah, I think it was when corporations became a really big deal and social events and corporations became a really big deal. You know, there was a lot of socializing. I don't think it was that big a deal during the Great Depression or the Second World War. So it was probably the late 40s, early 50s. And she's, in the last paragraph of the book, it's very, very interesting. She says, now, she says, if you don't remember any of this, I've got one rule. In order to have a great party, in order to have a great social event, make sure the host has a good time. Because then they'll do it again. No, it's just that the best advertisement for your company is actually that the owner is having a good time and shows it. You know, he just loves doing what he's doing. She just loves what she's doing. And the whole point is that you're kind of looking for people who are going to have a good time too.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, I think by good time, if you mean people that enjoy being together, laugh together, want to talk to each other, share ideas, whatever.

Dan Sullivan: They're going to enjoy coming to work every morning. You know, yeah, yeah. And I think that's the big thing. I mean, we have there's an interesting test. You're talking about the Netflix test. And I don't know what the source of it is, but we did it in our Chicago company and our Toronto company. And it was a series of questions, but one of them was, do you have a best friend at work? Okay. And the next question was, if you have more than one best friend at work, how many do you have? And on average in our Toronto and Chicago group, it was three and a half, three and a half good friends. that we would talk on weekends, we would do things together, you know, someone would take trips together and everything like that. And they said it's actually friendship that holds organizations together. And if it's nine to five and you have no contact with people before nine or after five, no contact on weekends, they said the organization doesn't really have enough glue to thrive.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, I mean, that makes sense. And it makes me think of the toll that remote work can take on a company. Because how do you build those friendships if you're only with each other once a week on Zoom? I think it's really hard, which is why I think that during COVID and during lockdown and during so many people shifting to remote work, that's why I think that it became really difficult for companies to have a culture You know, and so many people's social lives are tied into their colleagues at work, grabbing a drink after work, or, you know, whatever. In general, we're social beings. And so I think that all of those things together, you know, make big differences. Tomás had a quote which I really loved. He said that talent is always relative to context. And I thought that was terrific.

Dan Sullivan: Totally true.

Jeffrey Madoff: So why do you say that?

Dan Sullivan: Well, first of all, people aren't talented everywhere, but it's particular situations that people's talent. I mean, that would be true for me. I mean, I've spent 50 years designing the environment where my talent shows up. Basically, I've created a structure and a process and a place in the marketplace where my talent shows up. But there's just enormous number of different contexts where what I do well, one is I wouldn't be interested in showing up, and the other thing is I wouldn't have the particular skills to show up. I think that inclination is strongest in people who actually create and own businesses, that they need a particular structure, a custom-designed structure where their talent will actually show up. No, I believe it totally.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I think it's really fascinating because I think that your personality becomes an asset at work. And if it is a liability, as you get older, it's going to be harder and harder to find new positions. I think that on one hand, bosses hire, companies hire based on predictability. And I think that that's not necessarily the best thing to hire on.

Dan Sullivan: Well, first of all, I think it's the lowest common denominator. That's what I think. You can't make high performance predictable. That's right. I mean, you can't hire for high performance. I mean, it's a guess and a bet, you know, that you're going to get high performance. But I think that since it's impersonal, the hiring in most companies and corporations, what is the minimal acceptable lowest common denominator that we can live with?

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I think you're right. And I was watching a special on comedy and, you know, how television as it was reaching wider and wider audiences kept smoothing the edges of anything that could be deemed offensive or controversial because they didn't want to lose audience. And the result of that in so many cases is just mediocrity.

Dan Sullivan: Well, I think it's really led to the fragmentation of the marketplace because people really want edgy. And so it's almost like since the networks can't provide it because they're guided by their non-offensive situation, you have what I would say specialized niches where people go for their edgy humor. It's like comedy clubs don't seat 5,000, they seat 100 or 200. Because it's not everybody who's going to enjoy the humor. So my sense is that the fragmentation comes about the fact that people really want what they want. They don't want someone interfering with their likes or dislikes. You're kind of guessing what's acceptable to everybody. And I said, well, the answer is that it's not interesting.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right.

Dan Sullivan: It's just not interesting.

Jeffrey Madoff: It's like Groucho Marx's statement, which I love, is he'd never join a club that would have him as a member. Yeah. So do you think that companies should hire for predictability or casting for unpredictability?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I think you're casting for unpredictability. Yeah, you know, I think that, well, first of all, if you're hiring for predictability, it's going to be boring from the start. Mm-hmm. No, I mean, you're going to structure it in such a way that unpredictability can't happen. Mm-hmm. Yeah. Which, I mean, to people who are capable of useful unpredictability, that's the worst possible situation you can possibly get into.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, and I think that unpredictability can be the surprise and the discovery that really lights something up. Yeah. You know? One of Tomas's books was called The Talent Delusion. And he said something very interesting in that, and you and I have touched on this in other contexts, that there's no such thing as universal talent, only the right person in the right context. And, you know, I think you could be a tremendously talented designer. That doesn't mean that you're also a good business person. So your talents don't transfer from one to the other. And I think that a lot of times people overestimate how somebody's applied intelligence is across the board.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, you really see that in military history, you know, that, you know, a lot of people who became very famous for particular campaigns or situations oftentimes had a background of failure. You know, the Jimmy Doolittle, who did the first attack on Japan, you know, which it wasn't much of an attack, it's just that it was totally unpredictable and it caught the Japanese by surprise. And he had a reputation in Europe, he was a bomber pilot, that he wouldn't follow orders and, you know, and he was always a bit fearful of you know, that he was going to lose his rank, that he would be demoted into a bad situation. And they needed somebody just with the guts to do something just totally out of the blue, because they flew bombers off an aircraft carrier, you know, and they didn't even know if it was possible. And he says, well, we'll find out whether it's possible or not. but he was the right person for the right position. The Tibbets, who was the Enola Gay bomber, the one who dropped the first bomb, you know, he was 27 years old, you know, but he just was sort of fearless and a tremendous leader. He had tremendous leadership, but he You know, when you're in the ranks for being a bomber pilot, there isn't anything higher than a bomber pilot. You're going to be that. And it was very interesting when the decision was made by Truman to drop the bomb. Then it was a conversation from that point forward. It was a conversation between Tibbets, the pilot and the president of the United States. There couldn't be any interference by any other officer in it. you know, and it was up to him that this is the day we're going to go, this is the time we're going to go, and we're going to go. And that was a 27-year-old who had that responsibility. And afterwards, you know, they asked him, you know, did you have sort of real regrets? Did you have—he said, no, no. He said, I had a—what President told me is, he said, this is going to save 100,000 Americans from dying in the invasion of Japan. And he says, of course you would drop it. He said, I never lost any sleep with it or ever. But that personality might be Ron in a completely different situation. I mean, that's an extremely unpredictable situation in the scheme of things. So my sense is that there are talents that are just made for unpredictable situations. Well, I think that's right. Not for predictable situations. I mean, there's people who are great for predictable situations and you need to have them. You need to have them, you know, because you don't want everything unpredictable. You want certain things. You want to be creatively, productively and profitable, unpredictable in a very predictable fashion.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, hopefully the prediction is that they always come up with something interesting. Yeah.

Dan Sullivan: That would be, you know… Like the Pixar team, the team that they put together for Pixar. Right. I mean, they did a weekend together and they came up with nine themes and all nine themes became movies and all nine of them were big hits, you know. Anyway, yeah, it's really interesting. And then the question is, is your business based on predictability in the marketplace? Is, you know, a year out, five years, 10 years out, what is the predictability that you want to be known for? In other words, there's all sorts of things you could be predictable before, but you have to define that. And then what part of unpredictability, what part of it that things have to be unpredictable for you to keep your predictable reputation?

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, and people feeling either having the freedom to take a chance, As opposed to this, what often businesses do is make the stakes so high that people are afraid to do anything because they fear for their jobs if it doesn't work out. So oftentimes, you know, that predictability becomes a leavening that makes things not very interesting. You know, I was in a meeting with one of my clients. It was a Ralph Lauren. And there's like 16 people in the meeting. And the guy that was, you know, this was his project, but Ralph brought me in to do the project. And so, each thing I presented, he said, you know, that's an interesting idea. I don't know if Ralph will like it. Or, yeah.

Dan Sullivan: Is Ralph in the room?

Jeffrey Madoff: No.

Dan Sullivan: No.

Jeffrey Madoff: Because I would then just ask Ralph. Because that's the other thing is, Nobody else's decision meant anything. I knew I had to go through certain charades, but Ralph had the final. Sure. And so to me, you know, I learned, talk to Ralph, You know, this is pointless. So every time it was like, yeah, I think this is really interesting, but I'm not sure that Ralph will think so. I think it's a really good idea, but I don't know if it's gonna work. And I said to him, Jim, did you ever complete a sentence without the second half of the sentence negating the first half of the sentence? And I heard so many discussions like that in business. Because the main job became holding on to your job and avoiding any blame for things that didn't work out.

Dan Sullivan: Well, people get more rewarded for saying no than they do for yes.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. I think, which I think is not a good thing.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: You know, when we did the Victoria's Secret football game and, you know, they said, how are you going to do this? And I said, you know, I'll do it. I mean, I will figure this out. And I was looking forward to the challenge of how to choreograph all these models who are not football players, how do I make them look like they can be, right? And so to me, that was, okay, so this is fun. And what I thought about it is this is just like, you know, a big fight scene in a movie. You choreograph all of the action. so that it looks convincing. And, you know, I got women from the NYU volleyball team and women from this New Jersey, I forget the team, but it was a New Jersey professional women's football league, got the ones who were tall enough and slim enough, which is most of the volleyball players and some of the football players that, you know, it would be like Adriana Lima takes the snap and she backs up. And then you see this pass be thrown which is spectacular because it was somebody else wearing a jersey who I got right at the moment of releasing. You saw the ball take off and we followed the ball. So it was a split second. You never caught that that wasn't actually Adriana. And the president of Victoria's Secret, when she saw it, said to me, Wow, I didn't know they were so athletic. Well, they weren't. Except for Candace, who was a trained dancer, very coordinated, from South Africa, and she wanted to actually catch the football. And she had to catch it in the air, and then we had crash pads stacked up. And so we threw the ball and she dove and she caught it most of the time because she was just very coordinated and kind of a natural athlete.

Dan Sullivan: But she had done it. She had a background in athletics. Oh, that's right. That's right.

Jeffrey Madoff: You know, so anyhow, it was really interesting because when I got the gig, I guess the predictable aspect of me was that so far I've been able to deliver on everything that I promised. And they liked the idea so much, but were questioning whether or not it could be done. I felt confident that I could pull it off with the talented people I was working with. Ultimately, you don't know until you're doing it. But they went for it, and then it worked fabulously well. It was really good.

Dan Sullivan: But, you know… And Ralph, well, it wasn't Ralph, but whoever ran Victorian Secret liked it.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, well, you know, it was really interesting, and this has happened to me a few times, that the person at the top of the heap, in terms of their ranking, until they expressed their opinion, Nobody had an opinion. And when I did this film on Elsa Peretti, the jeweler designer who at the time was responsible for 22% of all Tiffany business globally, her work, and I did this documentary about her, and all the Tiffany brass CEO took over a theater, and this was being shown to all the top executives, of which there were like 25 before it was launched. And at the end of it, there was stone silence. And I'm at the back of the theater, and Mr. Chaney stood up and said, where's Jeff Madoff? And I said, I'm back here. Back where? I said, I'm at the back of the theater. And he faces me and he starts going like this. Then everybody stood up and gave me a standing ovation. And it reminded me of the scene, Fourth of July, it's based on a Preston Sturgis novel, Winter in July or something like that. But anyhow, the head of the ad agency says, when I want your opinion, I'll tell it to you.

Dan Sullivan: It reminds me that all bureaucracies are essentially like each other. And Solzhenitsyn in his Gulag Archipelago, you know, Stalin days, he talks about a party meeting outside of Moscow that's in some city. And so it's filled, the room is filled. There's about 100 people there and they're all officials. And the person who's running the meeting said, to the leader, and he got up and he started clapping to the leader. They had a big picture of Stalin to the leader, and the clapping went on for a minute, and then the clapping went on for five minutes, and then the clapping went on for 10 minutes, and all of a sudden one guy in the front just sits down, the whole room sits down, and the next day the NKVD, as they then were, picked him up and off to the camps he went. And the interrogating officer said, Comrade, never be the first person to sit down. But it's bureaucratic. You've become part of a mechanism. You're not an individual anymore. Groupthink has taken over. Groupthink and group behavior has taken over. But it's just a function of bureaucracy. It's where individuals are trying to be part of the machine.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, and to gain favor. I mean, I had seen that Preston Sturgis film, and so after Cheney started applauding and everybody else then stood up and joined in, I just thought of that scene. And you know, when I want your opinion, I'll tell it to you. Nobody felt safe enough to express their like or dislike until they found out what the leader thought. And It's really fascinating. And I think that one of the things that happens also when you're looking for leaders in a company, I think oftentimes leadership when it's being sought in a company is effective self-promotion. And that oftentimes arrogance or what appears to be self-confidence is chosen over someone who is quiet. And oftentimes that person that's quiet and listening to the others actually has better leadership characteristic than those with the bombast. Do you agree with that?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, my definition in the entrepreneurial world of leadership is totally different. My leadership is where an individual decides to create a capability, a new capability, and does it and has witnesses. And that's leadership. And it could be anybody in the organization. They just decide, I'm going to create a new capability that we didn't have before, and they create the new capability, and everybody else is inspired by that. It could be the owner, it could be somebody else. Because I think we're living in a network. We're not living in a pyramidical world anymore, where politics is the ingredient of getting to the top. I think we're in a network world, and we're, influenced and were impressed by other people's behavior in the network. Well, you mentioned Pixar.

Jeffrey Madoff: So I had interviewed Michael Arendt, and Michael won the Academy Award for Toy Story 3 for original screenplay. No, Best Adapted Screenplay. And he won the Oscar for Best Original Screenplay for Little Miss Sunshine.

Dan Sullivan: Good film.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, wonderful, wonderful film. And I said, what's a story meeting like at Pixar? And he said, really wonderful and kind of merciless. And I said, what do you mean? He said, because Pixar is totally driven by story. And so our job, when somebody puts an idea out there, is what holes can we poke in it? What works? And everybody agrees, this is not for showing off. We have set a high bar for ourselves, and how do we maintain that? And we maintain that by sharing a common goal and working together to achieve it. So nobody's rude, but they may not like something or may have a different suggestion and so on. But I think getting the right people around the table, that's, if you're successful at doing that, getting smart people who know how to listen, who know how to cooperate with each other, and who all want the others in that room to succeed. And that's not being Pollyanna at all. That's being effective leader, I believe.

Dan Sullivan: I mean, that really corresponded to my experience at the ad agency about brainstorming new ads, you know. That what would happen? You're just, you're sitting there and people have ideas and everything like that. And it was fairly democratic in terms of who came up with the winning solution. You know, I wouldn't say it was democratic. It was unpredictable. who came up with the winning idea. And then a whole bunch of ideas would coalesce around the winning idea. The big problem was how to make this seem like it was the perfect execution of the marketing strategy that the client had put together.

Jeffrey Madoff: Which you did how? Backwards. Reverse engineer the solution?

Dan Sullivan: reverse engineer your solution back to their marketing strategy.

Jeffrey Madoff: And so it also not only fits, it's they take ownership in a… I say, it's amazing how accurate we were with our strategy when we came up with this solution.

Dan Sullivan: But the two had nothing to do with each other. It was afterwards that you built the reverse logic back to them. I mean, these are corporate executives and big banks and big Kodak and Chrysler and everything like that, you know. They've actually never met a buying customer.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, I also believe that it's a very effective strategy to make them acknowledge it, make them think it's their idea. Oh yeah.

Dan Sullivan: And I think that that's… I will say it's prudent. Yes.

Jeffrey Madoff: No, you're right. It is. It is. You know, sometimes I can't help myself and I will say, wow, you know, when you suggested X, which they didn't suggest, I said, when you suggested X, wow, you were right. That was a great idea. None of them ever said, well, no, that wasn't my idea. It was always their idea. Yeah, and the thing is, what difference does it make? And if you're the entrepreneur and owner of the company, you want people invested in what they're doing. And if you're hung up with getting all the credit, that's gonna be a problem for you. You know, it's fascinating because how do you cast for leadership?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, well, first of all, who's doing the casting? Yeah, I mean, is it one leader casting for other leaders? I mean, who's actually doing the casting? You know, I think that really good teams know who the captain is. In other words, it's internally generated who the captain is going to be. Leadership comes out in situations. You put a whole bunch of people together. This is one thing that I've really noticed with Babs. You take Babs and put her in any group, and it requires organization and it requires the execution of projects. And with a very short period of time, she'll be the leader. She's just got natural leadership responses to situations, you know. And I don't know. I mean, there isn't any overarching authority who actually… all the leadership in the world. I think it's one of the real strengths of the United States is that leadership shows up in so many different forms and so many different kinds of activities. that when they talk about the leadership of the country, I said, you know, what are we talking about, 50,000 leaders of important activities who are, you know, somehow their activities are merging together and they're creating, I think the more variety of different talents, the more different variety of different projects that you have available, that variety of different kind of progress and achievement can be made. I think it generates enormously different kinds of leadership.

Jeffrey Madoff: And where do you think AI comes to play in that? And what I mean by that is you know, as if it works out as currently being touted that AI is going to do a lot of the routine work, you know, how curiosity and adaptability and those human qualities, even empathy, I think have, those are the human qualities that AI thus far has not been able to take on in any convincing way.

Dan Sullivan: I mean, my own experience that I think in more and more situations, AI is taking away the reward for being predictable as a human being. I think it's removing the pay for being predictable. I think it's removing the opportunity to be predictable. And it's encouraging you to be more unpredictable. I think, I mean, if I can just measure it by my own relationship with a app over February of last year, so going on a year and a half, is that the amount of creative input that I'm putting into AI projects is far, far greater than I ever would with my own. Because it's handling certain kinds of predictability, you know, I go along and I say, okay, I've got two paragraphs here, and I want you to combine the central message of both paragraphs, and I want you to create a third paragraph that has a different message, and it does it. Okay, but then I have to do something with that, you know. It'll do one step, and I'm finding it's a bit like tennis. I think my experience with AI or ping pong, and that is that I hit it and it hits back, then I have to hit it. If I want it to play with itself, it doesn't do much work. So I think that there's a certain kind of predictability that AI is capturing, we've depended upon human beings up until now, that is being gradually removed.

Jeffrey Madoff: which I think will make that human contact all the more valuable, all the more important.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I did my fast filter on Shakespeare and I made a lot of points. So I really went deep into your Shakespeare story. I think Shakespeare is one of our major themes. Yeah. I think we nailed the theatrical, I mean, he is the theatrical entrepreneur for all time. I mean, Without competition, he has no competition.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, it's quite fascinating. And that whole structure of the Globe Theater and the entrepreneurial nature of it, you know, was amazing.

Dan Sullivan: And I think this, if you're, you know, it has to do with who's doing the casting, I think really, that really comes out because predictable people will do predictable casting. They'll do stereotype casting.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes, well, that's right. I mean, you know, I started looking at movies differently as I got more and more into casting because, and this is, to me, an effective example, because it's true. How do you take a short Irish dancer and make him into a menacing mobster? James Cagney. There you go. And is there anything there initially in the profiles that would say, oh, he'd be great in that part? No, somebody's instinct to do that. And I love Cagney. I think Cagney was, that's another one that they threw out the mold, so to speak. It was just amazing. And you know, a friend of mine, when he was doing Ragtime, which was his last film, was his driver, would drive him to the set every day. And so he got a chance for like a half hour every day, 45 minutes, to talk with Cagney. And Cagney said, I'm a song and dance fan. I don't like doing the gangster parts. but I get to do the gangster parts because I am a song and dance man. And, you know, he makes them, it was like Billy Wilder said, I make one for the studio and one for me. And, you know, that out of the box casting without fail is really interesting. You think of Brando in the Godfather, the studios did not want Brando. He had to audition for it. And he agreed to do that. Now think of where he was and what he had to do to get that part. Nobody could have been better than him in that character, Don Corleone. It's just really amazing. But when you think of the casting that's done, that is so out of the box that it's brilliant. You know, it's really, really fascinating. So with, I think the unpredictability, that would have never been, Cass James Cagney is the mobster in the Roaring Twenties. That would have never happened had AI been around. You know, he would not have been a part of the choice selection going on. Yeah, yeah.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I think the unusual success of Casablanca with Humphrey Bogart and Ingrid Bergman. But not only that, but they had six or seven great actors in that film. Peter Lorre was in that film. Claude Rains. Claude Rains was in that film. You know, all the talent they had in there. Nobody was sure of it, you know, like it was a great surprise how well that film, because they had two writers and they had one writer wrote the action scenes and another writer wrote the love scenes. And the whole question of the chemistry between Ingrid Bergman and they never saw each other like they would show up and they would do their film. They didn't hang out together anything. She said she was more sociable than he was. He was a real loner. and he would get together. There was about an hour interviewer with her. She had never seen the film. She had never watched it. She had just seen it. She was close to the end and she saw it and she said, it's a mystery to me why it's turned out so well.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I think it's rare for an actor to know what that final piece is going to be and what it's going to look like.

Dan Sullivan: Not like theater.

Jeffrey Madoff: No, you know, you know who was they were originally going to cast for Rick? Yeah. Ronald Reagan. Yeah. I don't somehow I don't think it would have been the same film.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: Bring a chimp in, bring Bonzo in, it would have been a whole different. And we still have bananas instead of Paris. So you got any takeaways from this one?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, well, I think that we're on a major theme with casting out hiring and that, you know, that phrase that we have, which is that you automate the predictable and you humanize the exceptional. And I think that's the difference between predictability and unpredictability. Yes. Yeah. Yeah. And more and more, our world is heading in this direction. I think because of AI. I think AI is laying claim to huge areas of predictability.

Jeffrey Madoff: I think that's true. You know, and I think that every system, because humans are involved, can be corrupted. And, you know, that there are fantastic positives and terrible negatives. And the hope is that the positives went out, but the potential for those positives is tremendous, as is the potential for the negatives. Because if you just look at it as cheaper ways to do things where you don't need to staff up, that's not good. And I think there are jobs that are gonna be created that we don't even know what they are.

Dan Sullivan: Yep. My sense is there's all sorts of roles that are going to be created that we don't know what they are. Exactly. I don't think jobs are going to be created. I think roles are going to be created. I think this is our chance to free up the human race for roles instead of jobs.

Jeffrey Madoff: I think you're right. I think that's great. Yeah. So in an effort to be unpredictable, Yeah. But still being predictable. I will say thank you, Don Sullivan, for anything and everything. And I think that we stayed within our… Stayed within the framework, yeah.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. We're predictably unpredictable by being predictable in that framework. That's exactly right.

Dan Sullivan: Exactly right. Yeah. And we get to spend enjoyable hours together doing it. We do. Thank you very much.

Jeffrey Madoff: Thanks for joining us today on our show, Anything and Everything. If you enjoyed it, please share it with a friend. For more about me and my work, visit acreativecareer.com and madoffproductions.com. To learn more about Dan and Strategic Coach, visit strategiccoach.com.

Related Content

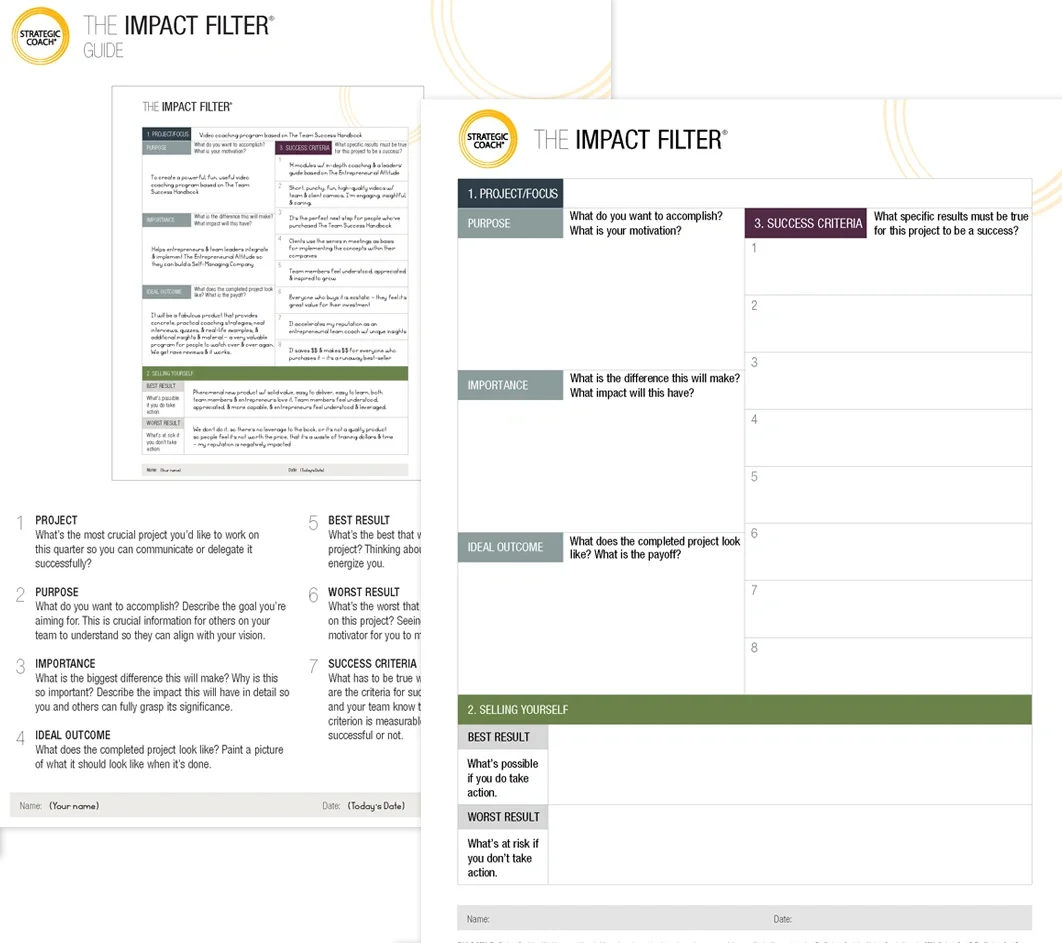

The Impact Filter®

Dan Sullivan’s #1 Thinking Tool

Are you tired of feeling overwhelmed by your goals? The Impact Filter is a powerful planning tool that can help you find clarity and focus. It’s a thinking process that filters out everything except the impact you want to have, and it’s the same tool that Dan Sullivan uses in every meeting.