Transform An Ordinary Sale Into A Remarkable Experience

June 24, 2025

Hosted By

Dan Sullivan

Dan Sullivan

Jeffrey Madoff

Jeffrey Madoff

How can you stand out in a crowded marketplace? Think beyond the product or service you’re selling, and make sure you provide customers and clients with an experience they’ll remember. Dan Sullivan and Jeffrey Madoff share the benefits of creating unique memories in “the experience economy.”

Show Notes:

Every purchase is an investment in a future experience. It’s rarely about the product or service itself.

In many cases, what you’re really buying is confirmation of status—a way to signal who you are (or who you aspire to be).

In the experience economy, people talk about how they experience certain products or services.

In essence, what’s being sold isn’t the product—it’s the memory associated with it.

How you feel about a transaction matters more than what you bought.

Nostalgia plays a big role here. We like things that connect us to when we were younger.

Humans are constantly integrating past, present, and future and creating meaning out of their experiences.

Identity is deeply connected to memory.

Resources:

The Experience Economy by B. Joseph Pine II and James H. Gilmore

Casting Not Hiring by Dan Sullivan and Jeffrey Madoff

Learn more about Jeffrey Madoff

Learn more about Dan Sullivan and Strategic Coach®

Episode Transcript

Jeffrey Madoff: This is Jeffrey Madoff, and welcome to our podcast called Anything and Everything with my partner, Dan Sullivan.

Dan Sullivan: It's Sunday, and on Sunday, the podcast Anything and Everything takes place. You're actually experiencing something that happens on Sundays, not just in Manhattan, but also in Toronto. That's where it happens. Jeff, we were talking a couple of weeks ago, and I think it was a book from the 1990s called The Experience Economy. And I was very interested at the time. I read the book, and I thought it made a very important distinction about business in the marketplace, which is usually people talk about products, they talk about services, and usually they talk about them as a commodity. And one of the things that I always felt that something that is a commodity that everybody loves more than another commodity, it isn't because of the price, it's because of the experience. That there's an experience that people have with certain products, certain services, that goes way, way above price comparison. How do you feel about that?

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I think that it is a true statement that people buy things and what continues to cause them to buy those things aside from obviously basic necessities. I have experience with toilet paper, but it's not necessarily something that I would say is part of the experience economy, but that's a commodity that I buy. But in terms of so many things, how you feel as a result of that transaction, that purchase, leaves a tremendous impact. And that impact is essential if you are trying to build a brand loyalty. And that can be H&R Block selling a tax service, or that can be Ralph Lauren selling the kind of articles of clothing and furniture and housewares that create the movie scenes that are the life that Ralph has created for the people that buy his goods. And all of those different things can make you feel good and cement that experience, so you go back. But how would you explain even the term experience economy?

Dan Sullivan: Well, first of all, I'd like to back it up a little bit. And I said, I think everybody, when they buy anything, they're buying an experience that's a future experience. And what I mean is, you know, a luxury car or Mercedes, let's use a Mercedes as an example. I think that what people are actually buying is being seen driving around in the Mercedes. I don't think they're actually buying the Mercedes. That they have a series of scenarios in the future that they're going to drive up in a Mercedes. And what the experience is, I'm not quite sure. The experience is that they felt badly about the car that they have when they drive to a certain place and everyone else has a luxury car. And so this brings them up in class. I think status has a lot to do with the experience. I think you're buying a certain confirmation of status when you buy a particular, you know, product or service. And my sense is that the person's mind, when they're buying anything in the present, they actually have a future context for what this means.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, I think that's true. And, you know, your comment about the car, the Mercedes, which is a great example, reminds me of I was shopping and a good friend of mine was with me. And we went to Zabar's, which has a great housewares department. I needed a tea kettle. And they must have had 40 of them, ranging in price from $19.95 up to $400. And I'm looking at all these things, and Doug Fielding, my friend, says to me, you know, they all hold boiling water. So which one do you like? And the funny thing is, a car is about getting you from here to there, unless you're on the highways a lot, which most people aren't. You know, why are you buying it? And I think that you're right. There's an associative memory of some sort with that and the status that accompanies that kind of thing. That really stuck with me when he said, they'll all hold boiling water. Really? What do you want a tea kettle for? But that, you know, and I think that's true with a whole lot of things in life.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Well, that would tell me that that isn't his particular experience.

Jeffrey Madoff: How do you mean?

Dan Sullivan: That is strictly the utility of the product that he's zeroed in on.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes.

Dan Sullivan: But if you ask your friend some other experience, he would have an equivalent, you know, that there's a particular type of product that gives him a particular type of experience. I don't know what it is, and I'm sure we don't know the full range of what other people find as valuable. I'll give you an example. It's a really interesting one. There's a great hotel in Santa Monica, right on the beach. It's the only hotel along there. First of all, it's a luxury. It's called Shutters. And it's just a really, really neat hotel. You know, it just got a nice feel to it. And whenever we do our workshops about, you know, 500 feet from Shutters, it goes up a hill and there's the main street there, Ocean Avenue. The hotel there is where we do our Strategic Coach workshops in Santa Monica, have been since 1998, I think. We stay there and the staff is fairly constant.

But what they give you in every room, they give you Swedish boxes. It's called Zündis. And they're really nice. They're actually pipe matches. They're not, you know, normal matches. And who smokes these days? But they always give you matches. And it's a little Zündis. And you can't buy them anywhere, you know, like we've tried over the years to buy them. So what I do is I'll talk to the concierge and I says, I'd like to have a package of tens and these matches when we leave here. And then there's an arrangement made and the concierge gets tipped and everything else, and I get my 10 boxes of the Zündis.

And I have them everywhere. We have them in Chicago at our house. We have them here. We have them everywhere we are. We have the Zündis. And what we've done is they're so hard to get that I'll buy other matches of the same size, take them out of that box, and I'll put them in the Zündis box. And I tell people this, and they say, Dan, you know, you're really weird. You're really weird. You know, like, boxes of matches. I said, I love Zündis, you know. But I think it probably conveys my experience of being at that hotel. And when we're not there, we have some of the experience of that hotel where we are. Because every time we pick up the box here, I think of Shutters.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, and I think one of the things with experiences, in terms of experience economy, is talking about how you experience that item and the memory that's associated with it. You know, to some people, they would see it as a box of matches. But to you, it triggers a certain memory of how you were treated, the place that you really like. And those memories, in the experienced economy, one would argue that what they're really selling you is the memory. The product is the memory that you get. Pine and Gilmore, who wrote The Experienced Economy, that's what they talk about. And that's the whole notion of souvenirs, right? As a result of your travel, that's one of your souvenirs. Every time you go there, you get those matches. You probably don't even use the matches up. You and Babs don't smoke. I don't know how many people smoke to come into your house.

Dan Sullivan: They're really handy in bathrooms.

Jeffrey Madoff: Okay. A different kind of experience.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, there's a wide variety of different kinds of experiences. And we have lots of candles around, you know, at nighttime when we have dinner parties, little lights.

Jeffrey Madoff: Motives.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, sort of, yeah. And the other thing is, for at least 30 years, when I get trousers, they always have pleats and they always have cuffs, which is 1940s, really. It's basically 1940s. But I thought the 1940s, late 1930s, 1940s is probably the most stylish period of menswear in history. I think it was like the golden age for menswear. Cary Grant, you know, and they had pleats and they have cuffs. And everybody says, so weird that you have pleats. And I said, yeah, I like them. It reminds me of the 1940s. Well, so what is it that makes something memorable? I mean, it happened when you were younger. I think we like to integrate our lives.

When we're 20 or 30 years beyond, we like something that connects us back to when we were younger age. I mean, there's a comfort. There's a sense of congruity that you haven't changed that much. I mean, we're all required to change lots of things as the times change, as the environment changes, but there's certain things I really like hanging on to from my earlier days.

Jeffrey Madoff: I mean, it's funny when you see somebody as they get older, like when I went to my 50th high school reunion in Akron, and I saw people that—this was more true with women, because most of the men had lost their hair, but there were those that still had the same hairdo they had in high school, you know, can't say they look great anymore, but that gave them a certain comfort and consistency, I guess, in their lives. And so they associate that style, you know, with pleasant memories or memories or something like that. And so, the experience economy becomes about creating those unique memories.

And I always wondered about it because, you know, another area of these memories is trauma. And you can remember some traumatic circumstances wipe out memory, but other circumstances remind one of the trauma. And as a result, they're very uncomfortable doing X that somehow triggers that response, that trauma response. But that's a memory too. And that was something that was memorable.

Dan Sullivan: It's very interesting. I've had a series of orthopedic injuries. The first one was when I was 12 years old. It was an ankle break. And then I had one a few years later. It was a broken arm. I've had broken Achilles tendons and everything like that. And every time, and you know, it was more or less an emergency visit to the hospital. You know, you were picked up by an ambulance and you were taken to the hospital. And in every case, I got extraordinarily good treatment and personal treatment from the medical staff, the doctors, the nurses and everything else. So I've always had a really great, positive attitude towards hospital. It's where other people, it's a source of fear, you know.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I remember feeling betrayed by the hospital because when I was a kid, when I was around 10, I had my tonsils out. And at that time, I guess they were offering a package deal. You'd get your tonsils and your adenoids, which I still don't know what the hell the adenoids do, but the adenoids would come out too. And I don't know if you got it where you grew up in Ohio, but do you remember Captain Penny?

Dan Sullivan: Oh, sure. Everybody remembers Captain Penny if you grew up in Ohio in the 1950s.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes, Ron Penfound. Remember, you can fool some of the people some of the time and part of the people all the time, but you can't fool mom. Anyhow, he talked about, you know, because I guess kids watching that were at the age where you'd be getting tonsillectomies, which they don't take out anymore, by the way, they actually block certain kinds of infection. But anyhow, he talked about how, and when you get your tonsils out, you can have all the vanilla ice cream you want. And so I remember thinking about this when I was literally in the operating room and they were dripping ether on something that looked like a strainer covered with gauze. And as I think back on it, it's like, what, I grew up during the Civil War? Bite this stick.

Dan Sullivan: We're going to take … They were still using ether when I was growing up.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah.

Dan Sullivan: And so anyhow, they put it, you know, they had sort of a cup. They just put it over your nose and mouth and …

Jeffrey Madoff: And the smell was horrible, which reminded me of what the janitor's closet smelled like in school, the cleaning disinfectants that they had there, which that always got me. But what I found out was when I woke up, I said, can I have some vanilla ice cream? They said, oh no, you can't have ice cream now. I said, what do you mean I can't have ice cream? You know, and they said …

Dan Sullivan: This is the deal.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, that's what I thought.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I mean.

Jeffrey Madoff: And so they give you something that I've never understood why people like it, which is called Jell-O. Non-food. And everybody has got the aunt that for a particular holiday occasion when they're invited over, they bring their Jell-O with the canned fruit suspended in the Jell-O. Anyhow, I got ice cream like one time. I was in there for like three days, probably you're in and out in the same day these days. And I thought, wow, can't trust adults. You know, Captain Penny sent me, sold me this whole bill of goods. So at least the hospital experience wouldn't be bad. And they didn't live up to the contract.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I was too, and mine were taken out.

Jeffrey Madoff: Really?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, and it was in Euclid. We lived in Rocky River, so west side to east side. But it was a day of a great blizzard in Cleveland, and my mother dropped me off, and she had to go back and do something with the kids, siblings, and then she was going to come back, but she couldn't come back. So I was left overnight and then went through the operation without my mother. She said that I was, you know, I was born a happy kid. I mean, she said, you're just very, very happy as a kid and, you know, sort of, self-entertaining and self-educating, you know, I just, you know, sort of took it upon myself to keep myself occupied and busy. But she said that she was really worried that I would be scared, and I came back, and she said it was no difference.

But the next time she took me to church, the nuns were there, and I froze like this with the nuns, and the hospital was run by nuns. And I think somebody treated me meanly. And I remember that. And I always had this thing when you're around nuns. It isn't that I hate them, but you really got to be wary. You got to be wary around them. You know, that you have to be on full alert. You got to be on full alert. You know, you never know what one of those women in black are going to do.

Jeffrey Madoff: Wasn't that Tommy Lee Jones? Oh, that was Men In Black. Tommy Lee Jones, not women in black. I'll get the pen.

Dan Sullivan: I think it's a way of integrating our lives. We've spoken a lot. It's probably one of the attractions of the podcast series to us because we have 70 years of memories that go back to more or less the same locale in the United States, you know, and I think that we're constantly integrating present, past, and future. You know, we're pulling things together. It has to make sense. I mean, we're meaning-making creatures. We have to create meaning out of our experience. You know, although I think that's true, I've always … You're going to disagree with me.

Jeffrey Madoff: I think that's true, too.

Dan Sullivan: Or are you going to add something that gives it more profound meaning? Straighter depth.

Jeffrey Madoff: It's what makes things memorable, what makes things stick. You know, yes, there's that commonality of experience and so on, and how we tend to, unbeknownst to ourselves, even rewrite our memories.

Dan Sullivan: And that I'm convinced of we, my feeling is someone who has a fixed memory has a fixed, you know, that in other words, everything happened exactly the way you think it happens. You're just not learning.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. That's right. And so how, you know, I thought it was really interesting when I was reading Pine and Gilmore and The Experience Economy, I thought was really interesting when they said that memory becomes the product. And a friend of mine has a quote, and he says, yeah, that made a lot of sense until I thought about it. And I don't think that, you know, the memory isn't the product, but the memory is a by-product that makes something memorable. And I think there's, I think that there's a difference.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, well, I think the thing is, I don't think that saying that the memory is the product is commoditizing the memory. Okay, it's commoditizing. I think the memory is an experience, okay, and I think an experience surpasses a commodity.

Jeffrey Madoff: Oh, I agree. I agree. You know, I mean, the nature of commodities are, you know, you can buy, most things are commoditized and it's those that are unique and aware enough to build a brand and a brand experience around it that differentiates and can command premium pricing. And I think that's the case. But there are so many things outside of business. There are so many things that we do to preserve memory, because something was memorable, it was somehow had an impact on our lives.

Dan Sullivan: Well, it had great meaning.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes. Yeah. So I mean, do you have an example, like, I guess you're, you're talking.

Dan Sullivan: Well, I was just thinking, we've just purchased more land up north where our cottage is, and it's got a, it's got about a five-acre woods. It's on a big hill, but it's just pure natural woods. There's nothing in it. And I grew up on a farm that we had woods at the back of the farm. And that was a great treat when I was six years old. I got the right to go into the woods on my own, go down there and play. And I turned it into Robin Hood's forest, and you had all these other things. I had read the comic book story of Robin Hood, and then I transposed the story into the woods and everything like that. And throughout the years, I've always said, someday I'd like to have a woods again.

And we just got the woods. And I didn't even really think about it. It just came as part of the land where new cottages being built and everything else. And then one day I just went up into the woods and I said, oh, I'm back. I'm back. I'm back like that. But it pulls together. I left when I was 11 from the farm. So that was the last time. And now I'm 81. But I think it's a connection that there's meaning that you had a long time ago, that meaning is still in the present. And I think it has to do … My sense is that humans, at their best, are meaning-making creatures. And, you know, that's why the whole thing that we're information processors, you know, that the tech people talk about rakers, well, no, human beings are just information processors. It's not true. No, no, we're meaning-makers. We actually don't really care whether the information is true or not true or accurate or not accurate. We don't really care. Is it useful for putting together meaning?

Jeffrey Madoff: I think, you know, it's not that people don't care. I think they don't know. I don't think they know how they change their own narratives. And I think you have to be very, very aware in order to do that, which most people aren't.

Dan Sullivan: You know who really got this down, Pat, is defense lawyers. They really know what people do with their memories. A really good defense lawyer can get you to change your memory with about five questions.

Jeffrey Madoff: You mean a prosecutor?

Dan Sullivan: You No, a defense lawyer. No, it's the witness on the prosecution side and he says, well, it happened this way and I did it and say, wait, wait a minute, you know, and they'll ask five questions and all of a sudden they're not so sure that they saw what they saw or heard what they heard.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, then the memory becomes a blur.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, and then the prosecutor, a good prosecutor probably does it too, you know, it's part of the legal skill.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, yeah, and discrediting the witness. You know, you can't count on their memory what they thought was so certain, in fact, isn't. I just demonstrated that. But yeah, there was a dead-end street in our neighborhood that bordered woods and not big woods, but woods. And there was a pond, not fit for swimming, but you go down there with a mason jar and you could fill the mason jar with water and you'd get a bunch of tadpoles. And I don't know who built it, but there was a kind of a rough raft and this was not a big pond, you know, maybe 20 feet across, 30 feet across at the most. I have no idea how deep it ultimately was. Nobody ever swam in it. But it was this mysterious gathering place for us.

Dan Sullivan: And your brain did all sorts of things with that pond when you were down there.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. That's right. And so, you know, when you think of those things, and I think about stuff that I like, the stuff that I like, whether it's actual physical record albums, which I like, you know, actual pictures you can hold as opposed to look at it on my phone. I like physical objects. And, you know, and I think about where memory comes in and how do we try to preserve memory. And so I think that that's a fascinating area to me, because memories, this is where I think memories become the product. Snapshots, home movies, diaries, journals, all of these things that are the manifestation. And we write down, of course, if you ever kept a diary, if you ever kept a journal, you know, we remember what we want to remember from those things. And sometimes things can be really vivid.

And I mean, I saved lots of my old writings, and there are times that I have zero memory of what the origin of that was. For the most part, it's pretty well seated. And to me, reading has always been an important and enjoyable activity. And so the things that I wrote that I liked, I tried to preserve. But the home movies, all of those things, I think are the by-products of memory, do we need them? No. But do they enhance the possibility that you'll remember things, whether accurately or not? I think it's really interesting, because also memory is associative. So when you, all of a sudden, if you see somebody, you're gonna remember other people that you hadn't thought about for years. And so it gets back to, again, then what is it that makes something memorable? Why do we want to preserve memories?

Dan Sullivan: Well, who you think you are is very tied up with your memories. Things that are still meaningful decades later has a certain solidity to it. It has a certain foundational solidity to it. You know, and I think that it depends upon your awareness at the time. You know, like I think about your movie theater in the basement of your house, you know, that was a very formative experience, you know, given what you're doing today. Yeah, you know, you were putting butts in seats back then and your whole goal is to put butts in seats today. But the other thing is that you were taking an ordinary basement and you were turning it into a special place. And you didn't stop there. You put up posters, you know, you had popcorn, you had everything. You know, you kind of imposed an imaginary reality on an actual place and got away with it. I mean, what's wrong with that?

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, it was fun. But, you know, when you used, you just used a phrase that most often is used pejoratively. Who do you think you are? Well, I know, but do you?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. I know who I am. I know who I am. Do you know who you are?

Jeffrey Madoff: That answer would really disturb some of my teachers, you know, when I came back at them with, you know, who do you think you are? And I said, well, I know who I am. I'm not you. And there's no chance. Many years later, after the first time I was disciplined at school, because my teachers either really liked me and I got along great with them, or they didn't like me at all.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. No melodrama.

Jeffrey Madoff: No, I learned the belief that, you know, which is, it was fine with me. My belief was that you're not going to get along with everybody. I don't deliberately antagonize anybody or anything, but, you know, I look at it, it was funny, one of the fathers at the school, there was a graduation party for the kids. And there was a party at this place, this is when our kids were graduating from high school. And, you know, I was spending all the time with the kids, because they were friends of my kids. And I was wondering, so, wow, you've got a next big step. This is a milestone coming up, your high school graduation, you're going on to college. Most of these kids were going on to college. What does that mean to you? What are you excited about? What are you looking forward to? You know, all of that kind of thing.

And I was talking to them, and one of their fathers came up to me and said, why don't you come up with us and have a drink? And I said, I find them more interesting. And he said, yeah, but you've been down here all evening with the kids. Why don't you come up and talk to us? And I said, because I know your story. They're setting off on a whole new adventure. I want to hear how they feel about it. I think that's interesting and exciting, and I like that. He said, you know, Jeff, you're an interesting guy, but I think that if you didn't put yourself out there so strongly, and people got a sense to know you a little bit more, I think that you could get in with some of these people in a way that ….

Dan Sullivan: You could go up in the world, Chuck.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. And I said, I'm actually doing this out of respect for them. And he said, what do you mean? And I said, I'd rather find out right away that we don't get along so I don't waste any time in this relationship and then move on.

Dan Sullivan: And it's always been the case, and the thing that's so wonderful is …

Jeffrey Madoff: Oh, the thing that they were missing where they were was talking, they were just drinking.

Dan Sullivan: Yes, and small talk.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, well, whatever.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Wish Jeff was here.

Jeffrey Madoff: I mean, it's funny, so I was gonna say what triggered that, the who do you think you are, jump ahead 40 years from that first experience. My daughter is in like fifth grade and the teacher said, no talking in class. And so Audrey asked the girl across from her, what page did she say to go to? And the teacher stands up and takes Audrey and her friend out of the classroom. And she said, I said, no talking. And Audrey said, I didn't hear what page you said to go to. And the teacher said, I said, no talking, you're disrupting the class. And then you could hear the class. In the hallway, you could hear them inside the classroom. And Audrey said, and she was like in fifth grade, and she said, don't you think it's more disruptive that you're out here with us two people, and you've got 20 kids in that room making all that noise? Isn't that more disruptive than what we did? And then the teacher said, I want you to go back in that classroom and I want you to keep your mouth shut.

And so I was told by, you know, this teacher reported her to the principal and this other girl, and they said that, you know, Audrey was talking and then she, you know, had talked back to the teacher. What do you think of that? And I said, she's right. It was much more disruptive. The teachers were out in the hallway. The teacher didn't gauge the effect of her action. And I can't disagree with my daughter. She was correct. It was more disruptive that the teacher was out in the hallway leaving the class unsupervised. And then I thought, well, that's my daughter. It was just kind of interesting to me.

Dan Sullivan: I want to get back to the Heinen-Gilmore book from the 1990s. My sense is that they were just at that point, they were just about 10 years into the start of the technological revolution, you know, and the internet was now available when their book came out. In my sense is because in the book we're writing, the conclusion of the book is that theater is theater, having your entrepreneurial company base itself on theater principles is actually a very crucial and necessary strategy to compete in a world that is pervasively more technological. And my sense is that whatever they were writing in the 1990s, it's doubly and triply. So the whole point of making sure that your business actually represents a very fundamental and meaningful experience to the people who are your customers.

Jeffrey Madoff: Absolutely. I completely agree. Because as we are more technologically connected, we are more as individuals isolated. The result is also the latest reading scores have come out. They're the lowest in modern history. Mass scores too. And critical thinking isn't even taught.

Dan Sullivan: Which I think is absolutely essential. I was noticing Harvard this week announced that they're going to do remedial math for all their freshmen students.

Jeffrey Madoff: Is that true?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Well, they passed a math test to get into Harvard. You know, what are they doing remedial math for? You know, yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: And so I think that that's symptomatic of a number of things. You know, I think there are kids who are graduating high school in those last two years, COVID decimated their education, not to mention that, you know, I think there's also just issues with how things are taught and all of that. But I think that because we're so isolated, emotionally, people feel so detached and removed from social interaction.

I don't think we have yet realized the dangers that go along with, and I'm talking about psychological dangers, that go along with, for instance, remote work. You know, social skills. I mean, it seems to me that civility is not a part of our day-to-day activity. It ought to be, I believe. And I think that part of that reason is the more isolated you are and the more anonymous you are on social media, where you can be rude, insulting, mean, all those kinds of things on social media and how that affects kids. I think that all of these things together create a much greater sense of isolation and anger and disassociation. And I think that going to work is a social experience. Being with your colleagues is a social experience. We learn from those things.

Dan Sullivan: Being in teams is a social experience.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. Yeah. And so how do you feel about that in terms of remote work, you know, yeah, you can say, I'm just as productive at home, I'm even more productive at home. But now my argument is, well, actually, you're not because there's a part of your social self that is not being exercised as a result. And I think that that's dangerous.

Dan Sullivan: My own experience of it has been very, very different because I don't feel, for example, the ability to do podcasting went through the roof when COVID started, you know, that I could do. I mean, if we didn't have Zoom, we wouldn't be doing a podcast series. There's a whole new structure and process that entered into our lives when we could do Zoom. And I feel, I mean, I feel totally connected, you know, to you, where you are. But I've always been sort of connected, you know, I mean, from childhood, you know, I always took part in games and teams. And, you know, I was always, I always enjoyed teamwork, you know, even on the farm, because I think the reason why we moved off the farm when I was 11 years old, that my parents realized that none of us wanted to continue with the farm.

But I enjoyed the teamwork, you know, from an early age, you had your chores and you had to do your chores. And, you know, everybody had chores of one kind or another in the family. And, you know, you did them in school. I always took part in school activities and, you know, I always played sports of one kind or another, you know, and I was useful. I won't say I was a great team member, but, you know, I was a good team member. I've always been a good team member like that. And, you know, the other thing is I had at a very early age a direct connection. I could talk to people much older than me, you know, and I could ask them questions about their experience. So I don't feel particularly, what should I say, impacted by technology.

Jeffrey Madoff: But I think there's a reason for that. And the reason is you and I did not grow up with social media. You went out to play with other kids. You weren't sitting in front of a computer screen. There are those schools that are enacting rules that you can't have your cell phone in the class. When I was teaching at Parsons, I had students turn off their cell phones and put them away. I didn't want to see their cell phones. I wanted them to be present in the classroom. I am hardly what you would call a disciplinarian, but we're there to focus and do some work and learn from each other, not stare at your phone. And so we didn't grow up.

Dan Sullivan: I have that with the entrepreneurs too. I mean, I'm 30, 40 years older than some of them now, you know, and I'll notice that it's gone beyond reason in the workshop room. And I say, okay, now everybody, I want you to mimic paying attention to me. I said, I don't care if you are paying attention, but from the way you look at it, it looks like you're paying attention to me. So, but you know, can I tell you just to break the thing, do you know how you get everybody's attention? You tell them a story. The moment you tell somebody a story, everything stops and they listen to the story. All they're saying is they're looking for something that's interesting. It's either on the phone or it's what's happening in person. The reason is that the ability to communicate in an interesting way has been lost. I think it's been lost.

You know, I listen, you know, when I'm at other people's houses and I listen to how the children are talking and they're trading mumbles. Pne mumbles something, the other one mumbles, but there's no story structure. There's no interesting information actually being transcribed. I think the thing that struck me most, in London where we stay, there's a Japanese restaurant across from the hotel, and we were in there, and there were eight teenage Japanese, I think they were Japanese, Japanese restaurant, so high probability they were Japanese. Yeah, 15, 16. And all eight of them were looking at their cell phone. During the entire meal, they were looking at their cell phone. Now, the only question I have, were they connecting with each other by their cell phone rather than looking to another person? But they weren't talking to each other. And I said, I think they're being disenabled from their future by having this habit of just looking at their cell phone. What it tells me, they don't have the skill just to interact at a table.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, they also have, you know, we all at this point know about the dopamine hit that happens when you get a ping on your phone. You know, all of the things that are this immediate, I think, destructive feedback, because most of those things, if you got it now, or you had that period of the day where, okay, you can use your cell phone from four to six o'clock, whatever the hell it is. I think that that would be different, but I think everyone is searching, and I'm talking about younger kids, because that's who's going to be taken over. And I think that the social skills we're talking about, it's not about mastering Zoom. I think Zoom is great, and it was a lifesaver for me during COVID and lockdown. But again, we didn't grow up with our fundamental means of communication, texting and sending pictures to phones.

And so we're not gonna be so effective. We'll use the tool for different reasons that serve our business purposes or even social, getting together with friends via Zoom, whether it's COVID or not. But I think that, these, I wonder about, I think about how I feel when I hear a Beatles song, you know, or hear something classic rock from that era or whatever. And I wonder about, I've often thought about, what are these kids going to be nostalgic for? You know, what are they going to attach? If you're spending all that time staring at the computer screens, you know, what is it that you're going to think about when you look back on your life? What unique experiences, which most unique experiences, you're out in the world doing something.

Dan Sullivan: It's very interesting. I think it was about 10 years ago. It was just something that was in The Wall Street Journal. And it would talk about the highest grossing tours, live music tours, and the groups that were doing it. And without any exception, the groups that were doing it were in their sixties and seventies. There were sixties and seventies, top grossing, you know, The Who and Led Zeppelin, you know, like… Paul McCartney. Yeah, and Rolling Stones, you know. Bruce Springsteen. Bruce Springsteen. The performers were all in their sixties and seventies.

And I think the reason for that, if you trace it back over the decades, you get to about the mid-70s, and there was still such a thing as a national audience right up until about 1975. Where, like, you know, when the Beatles were on Ed Sullivan, their first appearance in the United States was on The Ed Sullivan Show. Everybody had that experience. It was like Elvis Presley, you know, when Elvis Presley was on Ed Sullivan Show. Everybody had that experience. The grandmothers had that experience. Six- and seven-year-olds had that experience, okay? But things got fragmented, technology got fragmented starting in the 1970s and ‘75, so that there's genre after genre. You have your genre, other people have their genres.

I think it's the lack of common experience that interferes with people's ability to communicate. If you can't find, I mean, basically what communication means is finding common ground. And I think that even though they're using a medium, they're all using the medium, the messages are all different that they're getting on the medium. They're all getting different messages. Like I was watching, I've never been on TikTok, but something threw me into a TikTok. I was tracking down something and I think it must have been a subject. And, you know, the search engine put me into a roll of TikTok. And, you know, they were like, you know, 30 seconds to 60 seconds. There was one and then there was a totally different one. And then there's a totally different one. There was no theme to it whatsoever. The only thing that held it together is that it was the medium that held it together.

And I guess that's what Marshall McLuhan meant when he said the medium is the message. But it's not nourishing, you know, it's not very nourishing, because your brain has to turn channels every minute. There's no continuity to the message. And it puts you into a passive state, it puts you into a very passive state, and you just run out of energy to respond after a while.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, I think that what also happens is, you know, you don't have to respond. If you're doing what they call doom scrolling on your phone and you're just going like that on all the Instagram feeds and everything else, that's not interaction. Liking something doesn't mean liking, like we know what liking is. You know, you don't friend somebody. Probably the dopamine.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. No, I mean, there's another way of handling, never be on it at all. That's another way of handling the whole experience is just don't have the experience. I mean, I wouldn't know how to get on social media. I've never been on social media. I haven't been on Facebook. I haven't been on any Instagram. I've never been on it because it just seemed to me that there was no value to it, you know.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, I actually have never put anything personal on social media. I didn't use it for my company, which in my case, because I didn't, I never had a social media manager. I was creating lots of content for social media for, especially for Victoria's Secret, but I had never had any interest in sharing my life on Facebook or Instagram or anything. No. And never did.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: You know, I think, yeah, you're right, you can go off at all together.

Dan Sullivan: That's the way I've just, you know, but probably your point about the two of us were born at a different age, we had developed our own way. I'm a big reader, right from the moment I could read, I'm a big reader. I'm more of a reader at 80 than I was at 70 because I stopped watching television, you know, altogether. And, you know, I'm, I got about 800 hours a year back and, you know, I'm reading an enormous amount these days. But, you know, and I grew up on radio too. So even when television came, I was still attached to radio. So it was probably a generational opportunity not to get hooked on these things.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, I also think that how you use something, you know, using AI as a tool, as opposed to speculating. I think that it's important to speculate what the impact of something is going to be. I mean, the train has left the station, as they say, in terms of social media, because nobody was asking the right questions or any questions at all when it first started. So I think looking at potential consequences and ramifications are important. The impact negatively has been substantial.

Dan Sullivan: Do you think there's any way of doing that? Of knowing what the consequences of something new is going to be?

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, I think that if it's possible, you only discover that through discussion, not through just leaving it alone.

Dan Sullivan: The European Union has a thing called the precautionary principle. If something new today can harm somebody in the future, we don't do it today. And I said, boy, that sure cuts off a lot of the future.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I don't know that it's exactly like that, so cut and dried. But I do think that they have done some smarter things in terms of social media and kids, but it's not a total shut off valve. But I think that, I mean, it's like so many things. Most times people don't respond to things until it impacts them. And at this point, though, with things like that, it's impacting tens of millions of people, hundreds of millions of people globally. There's impact to it that we could have never anticipated, certainly without having conversations about how could this be used. That kind of speculation is done about so many other things. And I think it's something that so messes with our minds. It would have been great if there were smart people trying to determine both the good and the bad and how do you make it more good than bad.

Dan Sullivan: Maybe what we were lacking during this period was really interesting adults. And the children had no choice. The adults were so boring that they had to go to something else. I had interesting adults when I was growing up.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, you also had the opportunity to discover that.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: Which is a whole other thing. I mean, I don't think we yet know the consequences of kids that were just beginning to get data on, you know, these kids that spent formative years online, social media, and so on, increasing suicide rates. There's so many problems that have arisen. And you know, anything you take in regularly, whether it's social media or tobacco products or food, whatever, there's at least some discussion about it. And this just kind of exploded. And I think everyone was unaware, and I guess because it was so uniquely new, who could have known? But we do know now, so there's no excuse not to try to understand what's going on. When television started, there were two phrases that came out at essentially the same time. One was, television is the window on the world. The other was, television is the vast wasteland.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. And both are true.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, both are true. Both things can be true at the same time. And, you know, I guess my bent is, I would rather have things tilt more towards the positive and beneficial. And I'm not trusting enough of the general populace to just leave it up to chance.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Well, who would control it?

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. Well, that's right.

Dan Sullivan: I mean, most of the people who would like to control something, you know, I have worries about that. You know, I mean, my own experience, because we're hiring, you know, we hire a lot in their twneties. So these are people who have been through, we have a rule, you can't do social media during work time. You can do it at a break if you have a break or something like that. But our work is interesting, our teamwork is interesting, and it'll be more so as The 4 x 4, you know, gets into play. And, you know, I'm going to talk about that, how we're progressing with that in one of the last chapters of the book. It's actually a working model of people using it and everything.

But, you know, I've got a lot of clients now who are showing up in their twenties because technology is enabling really young people to make a lot of money at a very early age, you know, I mean, they have to make 200,000 to qualify for our first level. So there's, you know, there's a lot of people, they're bright, they're interesting, you know, but I think our program attracts a certain thoughtfulness, you know, that there are people who thinking about their thinking as they understand that this is really a key skill to being an entrepreneur.

Jeffrey Madoff: I think to be an engaged human, you know, I think it's an essential skill.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, yeah. You know, I mean, we don't know what life was like in the old days. We, you know, I mean, because the chroniclers of the past decades, past centuries in that they were reflecting the society that they intermingled with, you know, that they didn't have any contact. I mean, first of all, probably a hundred years ago, just an enormous number of people, well, 1900, 1910, an enormous number of people were just drunk most of the time. No, no, I mean, they were drinking alcohol that not only made them drunk, they were drinking alcohol. There were no standards or regulations on alcohol, you know.

The children who looked, you know, like very, very dull were probably cocaine. So that a lot of the pacifiers the children were taking just made them, you know, how do you quiet down a rambunctious child? You give him Coca-Cola, which had coke in it. That's where the coca comes from, the cola. The thing is that there's a big population. You know, the population is so much bigger right now. When I was born, there were 2.2 million. That's 1944. The world population was 2.2 million.

Jeffrey Madoff: Now it's not 2.2 million, it’s 2 billion.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, 2.2 billion, now it's upwards of 9 billion. And, you know, that's four times change in an 80-year period. That's a big thing. So I think one thing, there's just a lot of people around today, and it's hard to get a handle on whether they're, you know, better or worse than people at a similar age in a different time, you know. I mean, a lot of the people you graduated from in Akron, did they, I mean, yours did, because you were, you know, you selected a particularly bright group of people—ambitious, talented, you know, successful, but probably the vast majority. I mean, I went home for a reunion 25 years after I graduated from high school and they were already talking about retiring. I got back and they said, somebody asked me, you know, I wasn't. And I said, there's a reason I haven't seen them in 25 years. First of all, there's a lot of sensationalism in the reporting. Maybe there's just a lot of good kids out, but they don't get the attention of the reporters who want to make a case.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, well, I think in the things we're talking about, the people making the case are oftentimes psychologists, people involved in human development, people who are trying to understand what's going on.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, and they're also trying to get money to solve the problem. Probably some are. I think a lot of them are.

Jeffrey Madoff: But I also think there are well-intentioned, intelligent people who are trying to make people aware of what's happening. You know, and then it's a question of, you know, who do you listen to and how do you vet the information and all of that kind of thing. But I think that a horrifying example to me is, you know, the kid that shot the healthcare CEO.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: Mangione. Yeah. that I think it was in less than a day because he was a good-looking kid or he is a good looking kid. He was getting proposals of marriage. There were all these …

Dan Sullivan: And his GoFundMe is up to $350,000. I was reading the other day.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, but, you know, I mean, there has always been that. It just spreads a lot faster now. Yeah. But the thing is, you know, I look at that and think, wow, you're trying to make a full cure out of somebody that killed somebody else.

Dan Sullivan: Well, they did that with bank robbers in the 1930s.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, yeah. I mean, Jesse James was a hero to people. Billy Pitt was a hero. I understand that.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. John Dellinger, you know, Machine Gun Kelly. The Parker gang, Ma Parker.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. I mean, we've always deified outlaws of a certain kind.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, well, there's also, we suspect that there's villains in society that, you know, deserve to be shot.

Jeffrey Madoff: You know, I mean, that if you have Robin Hood, you got the Sheriff of Nottingham, you know, like… No, I don't think that basic human nature has changed, you know, since societies became organized. I mean, I think you look at ancient Greece and there's a lot of parallels to what's going on now. You know, I always wondered when they're saying in 200 BC and I'm thinking, how'd they know it was BC? You know, that always flummoxed me. How did they know it was BC? But I think that when you're talking about human nature, I think that's essentially unchanged. It's just our way to tap into it the way it's manifest.

Dan Sullivan: I think what people have to deal with changes.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes.

Dan Sullivan: But I don't know that their responses change. Yeah, I think a big thing, you know, and Joe Polish has a lot of insight to this, that the whole thing about dopamine and, you know, that we have drugs inside of us. We don't realize it, that like everything that you can experience as a drug from the outside, we already have that experience on the inside. You know, Joe has gone through a lot of negative experiences, which he's very forthright about. But I think that there's an ability to get addicted to substances, to experiences today that overwhelm your brain's ability to think about it in a rational way. And I think it happens at a very young age. I think most addictions in life probably happen probably around 14 or 15 years old. You know, the human brain has not fully developed until age 24. They're pretty clear about that. Your actual thinking ability, rational thinking, critical thinking, you don't have it at 14 or 15 years old.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, and I think that addiction is its own issue. And I think that treating it as a disease, which is how it's being looked at, as opposed to a human thing, as a crime. Now, it can cause criminal behavior if you're trying to feed an addiction. I mean, this is a whole other kind of a topic. But I just think that the problems we deal with as people are evergreen, whether it's addictive behaviors, violent behaviors, things that are the birth of altruistic movements. I mean, all kinds of things. I just don't know that that changes. But I think what technology has enabled to happen is getting the word out and congregating people in a much, much faster way than ever before.

Dan Sullivan: Well, I think that what we're working on here, what you work on, you know, period, with the movement upward of the play Personality into you know, the major leagues of all theaters, and with the book we're writing, Casting Not Hiring, I think what we're doing is bringing back a great deal of human connection back to the workplace. That's what we're, I think that's what we're doing here. You know, I'm very, very aware of it because we have a fairly large team at the company, 120. You know, it's not a small company. It's a medium-sized company.

And I deal with hundreds of entrepreneurs who have themselves have teams and everything else. And my sense is that we're taking a very positive, very productive approach to how you get people to engage with each other in you know, an arena that uses up the majority of their daily time for most of the days of the year. And I think we're doing a real service with what we're doing. And they're going to have some kind of experience. Why don't we give them an experience that's really a healthy and positive and creative experience?

Jeffrey Madoff: I completely agree with you. And that is the goal, to help people know how to engage that could create more fulfilling, gratifying, profitable business growth situation. And again, that means engaging with others. So how do you do that in the most effective way possible?

Dan Sullivan: Dr. Samuel Johnson, who wrote one of the first dictionaries in the English language in the 1600s, early 1700s, he says, I can think of no activity more harmless than the making of money. I could certainly question that. There's lots of harm that has … No, but in terms of what happens in 95% of what happens every day, the activity of making money, you know, the exchange of value for value, you know, is probably prevalent.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I think that there's a great deal of the world that functions in a more positive way. And, you know, the problem is often is that those negative impacts can be pretty large. But I think that it's important to stay informed and stay engaged and to stay curious and keep educating yourself. And I think that's an area where you and I also bond. It's that curiosity seeking knowledge. We may not agree on everything, but even the disagreements are respectful. And because it's all in the quest of learning, which I think …

Dan Sullivan: Well, and creating solutions.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes. Which is what we're doing with the book. That's right. That's right. So we got on this …

Dan Sullivan: I think I think we've done well.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I think that in the anything and everything category, we were remarkably focused on a couple of topics, which since it's an accident that we were.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I don't want this to get out of hand of us.

Jeffrey Madoff: All righty. Thanks for joining us today on our show, Anything and Everything. If you enjoyed it, please share it with a friend. For more about me and my work, visit acreativecareer.com and madoffproductions.com. To learn more about Dan and Strategic Coach, visit strategiccoach.com.

Related Content

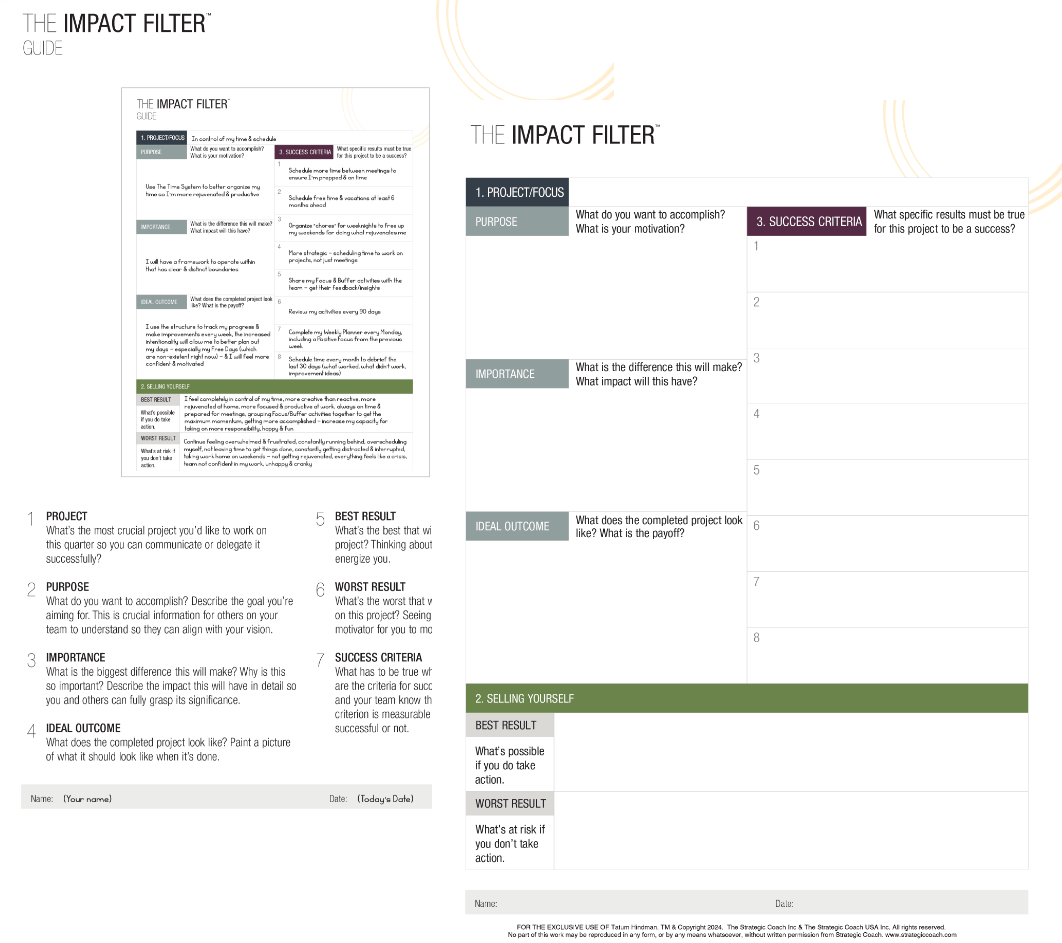

The Impact Filter

Dan Sullivan’s #1 Thinking Tool

Are you tired of feeling overwhelmed by your goals? The Impact Filter™ is a powerful planning tool that can help you find clarity and focus. It’s a thinking process that filters out everything except the impact you want to have, and it’s the same tool that Dan Sullivan uses in every meeting.