Why Rich People Don’t Stay Rich

June 10, 2025

Hosted By

Dan Sullivan

Dan Sullivan

Jeffrey Madoff

Jeffrey Madoff

What does true wealth look like beyond bank accounts and net worth? Dan Sullivan and Jeffrey Madoff explore generational wealth, the pitfalls of financial success without purpose, and why relationships, time freedom, and fulfillment matter more than money. Learn how entrepreneurs can build lasting value—without losing themselves in the process.

Show Notes:

Wealth isn’t just net worth—it’s the freedom to focus on what matters most, without financial constraints.

An entrepreneur can pass on the results of their talent, but they can’t pass on their talent itself.

The wealthiest 20% rarely stay in that bracket for long. True sustainability requires reinvention, not just inheritance.

The distance between "rich" and "poor" isn’t a gap—it’s a ladder with multiple rungs, and movement happens in both directions.

Taxes don’t just redistribute wealth; they reveal how fragile financial success can be without strategy.

Generational wealth often persists due to lawyers and accountants, not the achievements of descendants.

Once you’ve maxed out what your efforts can bring you, you have to multiply your income by working less.

It might seem counterintuitive, but you can spend your time doing only what you love doing and find people who love doing the rest.

True confidence in business comes from pricing boldly—charge what scares you, plus 20%—and eliminating "maybes."

Wealth without relationships, purpose, or peace is poverty in disguise.

Resources:

The Psychology of Money by Morgan Housel

You Are Not A Computer by Dan Sullivan

Learn more about Jeffrey Madoff

Dan Sullivan and Strategic Coach®

Episode Transcript

Jeffrey Madoff: This is Jeffrey Madoff and welcome to our podcast called Anything and Everything with my partner, Dan Sullivan.

Dan Sullivan: This is my favorite thing to do on Sundays. We were just talking about some of the interesting aspects of New York City, which is just out his window. I'm in Chicago actually today. We were talking about the age around the 1880s, ‘90s, 1910s of the wealth in New York, just the extraordinary wealth. One of the comments that I made, I said, I've been in some of those big houses, the ones that still exist. And you can tell a real difference between the working areas where the staff, the servants, work for the wealthy people and the quarters for those who had meaningless leisure. They just had leisure with no meaning. And that sort of struck a note with you, Jeff. So you said, let's record this.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes, which is why I love our Anything and Everything podcast. Here we are again. And we were just starting off with a conversation before we began recording, and it seemed like a really good idea because there was a tremendous amount of wealth, as you mentioned. But aside from that initial generation, oftentimes purpose was missing in the lives of the offspring and oftentimes meeting with bad endings. We were talking about, for instance, that the Vanderbilts had a home in New York that was eight stories and had …

Dan Sullivan: Old city block.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. I mean, it's amazing. When you walk around New York now, for instance, and even you see these brownstones, you realize those were all single-family dwellings. And then you go by some of the places like the Carnegie Library, all these buildings that were homes. They're homes that many families live in, and it was just one family at that time. And to think of that kind of wealth is very interesting.

Dan Sullivan: The one thing that I always am struck by, that in the States, there's a churn from, it's about a five-step churn from the poorest people to the wealthiest people. There's the poor level, there's the rich level, and there's about three levels in behind. And it's a constant movement upward and downward. And actually, they say that people who are in the top echelon, 20%, for the most part, aren't there 10 years later. They've moved down. And people who are at the bottom have moved up. So it's not like it's a fixed wealth. You know, taxation has partly to do with that. The other thing is, and I see a lot with entrepreneurs, that the first-generation entrepreneur who has a lot of talent can pass on the results of his talent, but he can't pass on the talent.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, well, it makes me think of Henry Ford. And, you know, Ford stayed a powerhouse. And the biggest failure, well, I don't know if it was the biggest failure, it was at the time, was a car that was named after his son, Edsel. But, you know, it's kind of interesting that the car named after his son, who I think was supposed to carry on the legacy, was the biggest bomb they ever had. You were talking about the gap between the very, very rich and the poor and how some of the poor move up, some of the rich move down, and there's then that wealth that has been just generational, that has continued generation after generation, not because of any extraordinary achievements on the parts of the great, great, great grandchildren, just because there was so much money.

Dan Sullivan: And good lawyers and accountants.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. Yes, exactly right. And that's what did it. And I think that one of the problems that we deal with is the tremendous gaps between those categories, those five categories or however many there are. Those categories, those tremendous gaps make a huge difference in the social structure. And so I think there's a couple of things that are interesting. Like, what is wealth? How would you define wealth?

Dan Sullivan: Well, the easiest way is just what you're worth financially, monetarily. I mean, usually net worth indicates wealth, and net worth is simply if everything you had was purchased or sold, sold by someone else, what would be the total amount? That's one thing of wealth. But then it gets fuzzy around the edges, what wealth does. For example, in the Coach Program, and we have people, you know, they've been in Coach for 30 years. When they first came into the Program 30 years ago, money was very much on their mind. But one of the big emphasis that we put on very early, starts in the first workshop, is that they have more free time than they, how they manage their time to get to where they are right now.

We said, you've probably maxed out what your efforts can bring you, and now you have to multiply your income by working less, okay, because right now, you're not very creative right now. When's the last time you had a really great creative idea that really broke things open? You're really tired right now, and you're a bit bored with what you're doing right now, and you're looking for a breakthrough. And therefore, you have to just get back to what you really love doing in the business, which is maybe 20% of your time, and the other 80% find other people who can do what you're doing who would love it, who would actually love doing that.

And it's contrarian, it's a contrarian thought. And a lot of people just, they wouldn't trust that they could actually do that. But the ones who do it, usually they'll double their income in about three years if they do it. And the reason is that they're just fresher, they're smarter, they're noticing more things, but they've surrounded themselves with great teams.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, you've done that.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I've done that.

Jeffrey Madoff: So you do, in fact, practice what you preach. Which I would say the vast majority of people do not.

Dan Sullivan: I practice what other people preach.

Jeffrey Madoff: Now, I got them to, yeah. There's a writer named Kenneth Patchen. I loved his work. I'll give you a quick funny story about it. This is many years ago, 25, 30 years ago. I was at a party in New York. And there was this guy kind of holding court with a group of people. And he was talking about, you know, this place he goes, and it's a great place because all of these famous people go there, and he likes going there. And he happened to mention Kenneth Patchen, who was very big in the probably fifties and sixties.

And he said how he knows Kenneth Patchen. And I said, you know, Kenneth? He said, yeah. And I said, oh, I love his work. And he said, well, you want to meet him? I could certainly arrange for you to meet him. I said, I'm not sure that I'm ready for that. And he said, well, if you want to meet him, you know, I know I'm more friends. And this was last time he saw him. And he said, I don't know, within the last couple, three weeks, something like that. That's extraordinary. I mean, this is because he died 45 years ago. Special friendship.

It was so funny to me, but Patchen wrote a story about a guy preparing to die and he wanted to find out how much he could get for all of his possessions, like what you were talking about, down to, you know, selling his bones and the gold in his teeth. And I mean, everything was reduced to a commodity. And how much would that be worth? I thought that was really interesting in terms of, you know, so how do you value yourself? But I think it's also fascinating because there are many very, very wealthy people, at least seeming wealthy on the surface, but their cost of living exceeds the tremendous amount that they've earned. I'm sure you have seen that time and again.

Dan Sullivan: I would say that they like have a team that they've hired to manage their wealth. And I don't mean just manage the money, but manage the houses that they bought, manage the cottage that they bought, manage rehab for their children, you know, all the different things. It's very costly. Plus, they're pecked to death by everybody wanting some of their money, especially from a philanthropic standpoint. They get invited to everything and everybody wants a check. All the politicians know them and, you know, are asking for a handout. It gets very complicated after a while. And then they need security.

Jeffrey Madoff: And what type of security do you mean?

Dan Sullivan: Bodyguards, you know, extensive electronic security, you know, everywhere they are. What I've noticed is that they become defensive towards the world. They become very, very defensive. That if it was their goal, they might have just inherited it. But if it was their goal to become wealthy, it really didn't do for them what they thought it was going to do.

Jeffrey Madoff: And why is that?

Dan Sullivan: Well, I think it was more what other people would think about them, knowing that they were wealthy, that it would buy them recognition, it would buy them kind of celebrity to the degree that people want celebrity. Somebody that is known well in the coaching world, the coaching world's very, very broad, but he was at a clinic in Mexico and he had eight bodyguards with him.

Jeffrey Madoff: Really?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. And I said, that's an expensive clinic. It's a journey outside of their home. And everything else. And I said, you know what, my goal would be to be famous and wealthy just up until the point where you would start thinking about having a bodyguard. Just below, just below the level of visibility. You know, you don't show up yet on the radar screen. Yeah, but we've done really well. Both Babs and I are way beyond anything that we grew up with. And I go home and, you know, the in-laws will ask me and they says, well, you seem very fixated on money. And I says, actually, I'll tell you my fixation on money is that I have enough that I never have to talk about it. That would be my goal. I said, more than enough. Nothing would be unavailable because I couldn't write the check. You know, I've got some simple things. But I said, the other thing is that I have purpose for all of it. I said, I have purpose for my money.

Jeffrey Madoff: And the purpose being?

Dan Sullivan: Well, writing a book with you, you know, writing a book with you, contributing to just as it relates to us, your play, it gives me a great deal of pleasure, Babs and I, just to write checks to the various growth stages of the play. I mean, it's neat. And you don't even have to think about it. But the other thing is that it protects the company because we've had four or five situations in the first 35 years where we were the bank that kept the company comfortable during rough times, COVID being one of them. The 08-09 downturn. So we have a lot of reserve. The company can't be interrupted by, you know, market circumstances.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I mean, to me, that's the ideal description. You know, when you mentioned about that point just before you need security or you think you need security. I'm blanking on the guy's name, but he had a fitness company. He made protein powder and that kind of thing. I actually met him through Joe.

Dan Sullivan: Oh, yeah. Bill. First name's Bill. Bill. Yeah, I met him. He's the only client who's ever come to The Strategic Coach with two bodyguards.

Jeffrey Madoff: So, well, you've got a dangerous crowd there.

Dan Sullivan: You know that he complained about the food.

Jeffrey Madoff: I'm blanking on his name. I can't come up with him. But anyhow, funny you said that because Joe wanted me to meet him. He was coming to New York. So he shows up with three guys with him. Big guys. One standing by the front door. One of them that helped him take his coat off. One who tasted the food. And I'm thinking, you're in New York City. Nobody knows who the fuck you are. And they care even less. But I think of that. And it's funny you mentioned that he shows up at Coach with two bodyguards.

In Moscow when I was there with Ralph Lauren it became clear to me, and I talked to Ralph's head of security, wonderful guy, and I said, it seems to me that how many bodyguards you have is a status symbol. Some of these people literally had eight bodyguards with them, and they're wearing a Kevlar vest over their $5,000 suit. And he said, you know, it's not that they have so many bodyguards, you're right, it's a status symbol showing people how important they are by how much protection they need. But he said the real danger here to others is these guys, especially in the early 2000s, gunfights would break out like in the Old West.

Dan Sullivan: Bystanders would break out.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. Exactly right. That's right. But I was just reading an interview with Bill Murray in The Times, and it was kind of interesting because he is talking about how, you know, he used to enjoy walking down the street. And he can't because people come up to him. And you hear certain celebrities talk about, yeah, just going to the grocery to pick something up isn't like me going to the grocery to pick something up. I just go to the grocery and pick something up. I think there's a greater sense of being in danger, which is unfortunate. But I think that there are people like the one name we can't think of, just as an indication of how big a celebrity he was.

Dan Sullivan: There's this book, Housel, H-O-U-S-E-L, Morgan Housel, it's called The Psychology of Money. And it's a very, very good book. I mean, he's got these little, four-page chapters, and they each have a sort of a lesson or a mindset about money. But he said when he really, really understood, you know, he began to understand how to think about money for his whole life. And he's been an investor and everything like that. But he said that he was a valet, you know, parked people's cars at luxury hotels in Los Angeles. And he said, you know, I can look back and I can probably remember 25 really great cars over about a five-year period while he was going to college. He says, I can remember about 25 just amazing cars, but I can't remember their drivers. I can't remember their owners. And he says, so I'm thinking that maybe they got that car so they would be remembered, and I just want to let them know it didn't work.

Jeffrey Madoff: So speaking of that, my first accountant, really good man, one of his clients was Sammy Davis Jr. We were having dinner and he said, you know, I had to go to Vegas, meet with Sammy, because although he was making eight million a year or so, he was deeply in debt. And I said, you know, Sammy, every place you go, you got, you know, this entourage with you. They're all freeloading off of you. All of this money that you're spending, you're way exceeding what your income is.

Now, as he's telling me this story, I'm thinking, if I made, you know, 8, 10 million a year, I'd put some aside. So he said it got very emotional for Sammy and Sammy was crying. You're right. You're right. I know I got to get this under control. I don't want to go bankrupt and all that kind of thing. So he said, well, you just can't purchase whatever you see to frankly show off, you know, like the guys who bought the cars that now somebody else owns.

So they leave the room and they're going through the lobby of whichever hotel it was in Vegas. A bunch of people are standing around and they're looking at an Excalibur that was parked there. Somebody said in the crowd, Sammy, you should buy this car. This is perfect for you. And so he says, yeah, Sammy, you can get this. Anyhow, he buys the car. Like that. And Alex says, I realized then, I just wasted my breath, you know, having that heart to heart, trying to make it clear, because I think some people attach their self-worth to their beliefs.

Dan Sullivan: Oh, their identity.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right.

Dan Sullivan: That was a challenge to his identity if he didn't buy it.

Jeffrey Madoff: In his mind, yes.

Dan Sullivan: I had a sports agent in the Program for a number of years, really well known now, he's really at the top. But earlier in his career, he had taken over an NBA player, National Basketball Association player, because the previous agent hadn't done a good job. So he was doing due diligence. The agent that I knew was doing due diligence. And he was looking for lavish lifestyle. And it was straight out of high school to first team all pro. He was that good. He was out of Chicago and graduated from high school. And the next September he was playing in the NBA and he was a star—Hall of Fame, he's retired now. So the agents, Jimmy Sexton, he said, you know, I checked him all out and he says he lived in a nice home, but it was just a home that 50 people in the neighborhood had. He said he had three cars, but that's not such a big deal. And then I started digging deeper and he had 42 car leases.

Jeffrey Madoff: 42 car leases?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. All his buddies from when he grew up with, every cousin he didn't know about. And that's what depletes them. They're the ticket out for a lot of other people. When someone like that comes from nothing, goes to the top, they pull a lot of other people up with them.

Jeffrey Madoff: And then a lot of those other people, of course, end up falling out too. It's hard from the outside because if you hear that somebody is, and by the way, I want to issue a disclaimer that some of the years or amounts may be fuzzy because we're telling the stories here and we didn't know which ones. So I just want to say I may be off on a year or an amount, but the stories are true. And there are people that we might think, God, they're making a fortune. But you know, you can be making $8 million a year and be spending $14 million a year or more.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Well, first of all, in the States, depending on where you live, the government wants part of that. Not one government, a whole bunch of governments want that.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, and there are governments that make their living protecting your income, Luxembourg, so on, where you can hide your money, so to speak.

Dan Sullivan: Lichtenstein.

Jeffrey Madoff: Lichtenstein, yes. Lichtenstein. Thank you, yes. That was an example of my disclaimer.

Dan Sullivan: Exists only for that purpose.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. So, you know, when you think of wealth traditionally, you think about how much somebody makes, but it doesn't mean anything if you don't have the context of how much they spend. And if you are spending way more than you make, no matter how much you make, it doesn't make a difference. You're not wealthy. You're on the brink of debt or bankruptcy a lot.

Dan Sullivan: The other thing that we get our clients to do is to define the wealth they have in their life in every other category except money. But what else do you have in your life that you would consider your wealth? Are your friendships wealth? What you actually do that's really unique, does that count as wealth for you?

Jeffrey Madoff: Right, that's a great criteria. You know, because I think that there are many people who might not be considered wealthy in a traditional financial sense, but they are wealthy with an abundance of things that buoy their life and make them fulfilled. I mean, to me, it was always the money wasn't primary, ever. I did okay, but it was about if I'm gonna spend my time doing this, I wanna enjoy it. And with my business like you, there were times that, probably four times in the history of my business, where I had to go into my savings to just keep things going. And that was just a survival necessity.

Dan Sullivan: You have to do it.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. Yeah. And I think that's another thing with people who want to be entrepreneurs often don't realize is, you know, you're going to shoulder a lot more burdens than you thought you were.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. The only time our banks ever want to see us is when we don't need them. They see the cash flow coming through and it's not theirs.

Jeffrey Madoff: One of the things that I got from my dad is I never liked having debt. So I always paid off my credit cards. And when I wasn't making money, I didn't use a credit card so much. And as soon as I could pay off my home, paid that off, because I also wanted to make sure that I was protecting my wife and kids. And so all the stable things are in place. And, oh, you could take that money and your interest rates, and I understand all that, but no thanks. I don't want the debt.

Dan Sullivan: I like sleeping at night.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, that's right. I just don't want that. I don't want to leverage any essentials, because I won't sleep. I know there are people that, of course, have taken great advantage and good for them. It's just I'm not constructed that way. You know, I take plenty of risks in terms of what I'm trying to do, but …

Dan Sullivan: I'm constructed that way but Babs isn't. I get 500 in my ATM every two weeks. I don't know how I'm going to spend this. You don't let Dan near money. I've always known how to make money, but my skill did not extend beyond the receiving of it.

Jeffrey Madoff: Before we started recording, when you and I were talking and you were telling me about the homes, and you said you learned how to buy houses, but you didn't learn how to sell them. And it's not like it's always building up all this income property.

Dan Sullivan: No, I mean, there's no income. I mean, it just happens to be that Toronto is a constant growth city and real estate always goes up. So, you know, it's worth a lot. See, when I moved here, I moved here in 1971, and the city was 2.2 million. Today it's 7 million. So it's three times. And it's got real growth pains. You can tell it's stretched to the limit, but it's a destination on the planet that has a real nice quality to it. It's in a safe country. It's reasonably governed, close to the United States, but not in the United States.

So, you know, it's always growing. Toronto is just always, always growing, you know, and stretching outward now. But now they're going up. So they've designated 10 blocks in the corridor that goes about 30 blocks forward. And it's going to be a mini Manhattan, according to the civic plans. None of the buildings are as tall as Manhattan, really, but they, you know, 30, 40 story condos and everything like that, yeah. So the real estate, if you're close to the downtown, we're about a 20 minute drive from the downtown. So the real estate always goes up.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right. So you'll pass it on to your heirs is what you're saying.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, whoever they happen to be. I don't really think about that. Yeah, we're generous. Babs and I are both generous. So, you know, the money moves, but we have to be interested in the project.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, so that's what I wanted to get to is, you know, another thing about wealth to me, wealth is as much about personal sense of peace, fulfillment, gratification, achievement, whatever, but of course, it's very helpful to have financial wealth so that it frees you up not to have to worry about certain things, which is, again, one of the reasons I like to avoid debt. And I know the credit card companies don't like me because I've never not paid a bill every month. So they aren't making anything on me. So I don't care.

But anyhow, when you started Coach, it was not, you know, something, there's a gap in the marketplace. There aren't entrepreneurial coaches that make a killing. You know, I could make a killing doing this. So what attracted you to it? Because it wasn't like, you know, we hear, we both hear so many people, ‘cause we both know a lot of entrepreneurs about how they're talking about how much money they're making or how much they can make from this and all this kind of stuff which, other than when you and I talk, and you have fortunately been successful financially, but you have your other priorities aligned. But when you started out in Coach, it wasn't like, this is a surefire money-maker. Let me do this. So what is it that drew you to it?

Dan Sullivan: Well, I've always been fascinated in other people's story. I've always been fascinated with, you know, how people did what they did. Growing up as a kid, right after the Second World War, I was fascinated with the stories of the First World War, the Great Depression, the Second World War, you know, and the changes, the technological change, first airplane, first radio, first movie, you know, and I knew people from the late 1800s that had done that. And I'd just sit there, and then, you know, if they'd mentioned certain things, I would go to the encyclopedia and read up, and it gave me this sense that I was talking to someone who had been there. I just had this great sense.

But what I noticed also that if I asked them questions that required them to actually think about their experience in a new way, that they got all excited. They weren't just repeating a script that they prepared for that particular experience. But I said, you know, you were born in the 1870s, but when you were in your twenties, what do you notice had changed? And we were in farm countries, so most of the people I was talking to were, you know, from farm backgrounds. And they talk and they said, you know, I hadn't really thought about that. That's really interesting.

I don't know when I put it together that you could make a living doing that, but I wasn't trying to help them solve any kind of problem or anything like that. It wasn't really about their problems. I was just noticing that when they put two or three experiences together in a new way, they got very excited. They got very excited about the new experience. That's answer one.

The answer two is what happened to me when I joined the advertising agency that really the only, one of two jobs that I had had in my lifetime. The first one was I worked for the FBI in Washington. I was there right after high school. That was a job, and then I was in the Army, and that can be considered a job. But the first job I really had was as a writer with BBDO, big global agency, but this was the Toronto office. Since I was the new guy in the agency, then agencies generally are a product of mergers and acquisitions. So over the previous 30 years, there had been about eight mergers where this agency connected. So they were big now. They were the second biggest in Canada.

But where the agencies make their money is on media placement, so 17%. If the advertising for the TD Bank costs $1 million, the agency gets $170,000. That's how they make their money, and that pays for all the production work. everything else that they have to do. But then through these mergers, they get these fee-for-service clients, and these are mostly family businesses. So there was about 15 of them that had come along over the years, sometimes second or third generation. And they made me the creative guy on these little businesses. I worked on the big accounts, but not as lead writer.

And what I noticed right off the bat, that advertising wasn't the solution to the problem that they had. They had just been in the business, going through the business, and they didn't have any vision of the future that was bigger than what they had already experienced. And therefore, advertising wasn't going to grow them because they didn't have anything to grow to. So I just started asking questions, you know, and I'd put flip charts on the wall. I'd tear it off and tape it to the wall with two because otherwise the ink went through and got to the wall. So you'd always do two sheets.

I started saying, well, let's say it's a year from now, what do you want to have improve, you know? And they had never faced that question before. Well, next year is going to be like last year, you know, and everything like that. And then I started doing it. It worked with some people. It didn't work with others. But I enjoyed the experience. I say, well, then, you know, this is what you're achieving. Let's put some numbers to that. You put some numbers to that. And then you say, okay, what are obstacles to this right now? This had nothing to do with advertising. This was strategy. This was, you know, strategic thinking. So then, you know, I did that for a couple of years.

Then some of them would have like weekend conferences and they would ask, can you come for the weekend conference? So I went to my creative director and I said, you know, they're asking me to do this. Does the agency support this? And he says, sure, why not? You know, but I did it for free. The agency didn't give me any money to do it. But I started to work out that if I left the agency and I went out on my own, I could probably get clients and I could do this and then I could charge them. And that's how it started. And it was a big jump. I mean, it was a big bet and a big guess.

So this was ‘74, August of ‘74. And it was tough. It was tough because the people who already knew me, I could do it for them, but not all of them. I mean, there's maybe three out of the 15 that I did, but it was enough to make a living, you know. And then you survive three Toronto winters and you're still in business, you're probably over the hump.

Jeffrey Madoff: How did you even know, though, what to charge?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I actually developed a concept at Sullivan Strategy on pricing. It's the price that really scares you, plus 20%. Because between you and the other person, you're the only one who's scared of the price because they haven't heard the price yet. So you say, well, that'll be … I remember the first one, I think my first one was, $500 for the first session and then $1,000 for three more sessions, something like that. I think it was like $2,500. This wasn't bad money in the 1970s. But I didn't have any sense of the structure of business, kept my finances in my head.

Jeffrey Madoff: You hadn't really created a company, you've just created a job for yourself.

Dan Sullivan: I was really sloppy with my finances, you know, and then you got to constantly be marketing. There's the executing and there's the getting paid, but there's also the marketing. You're okay for the next six months, but there's another six months beyond that to do that. So it took a while, a couple of bankruptcies, a divorce, extreme market research, as I call it.

Jeffrey Madoff: But was your divorce before Strategic Coach started?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, yeah, it was just me out there doing these funny drawings. You know, I mean, Strategic Coach officially starts in ‘89, starts with the workshop program. And we had the name before, but The Strategic Coach Program really starts in ‘89. And Babs, I had to meet Babs because Babs had a good head for business. She had a good head for running a business and how you staff up a business and everything else. So without Babs, there's no Strategic Coach.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I mean, it's wonderful that you two have such a great partnership on so many levels. You know, it's terrific. So I'll give a counter example. I mean, when you mention whatever the price is plus 20%, but initially when you're starting a business, of course you'll want the business and you don't have the experience behind you yet to even know what that first number is. I was interviewing this artist who did my class and her work, terrific work. And she does these paintings using her fingertips, and it's photorealism. Her technique is incredible. Her work is beautiful. I saw a segment about her on CBS Sunday Morning, saw that she had a studio in Brooklyn, and I reached out to her, and she was generous to come and do my class.

And I said to her, so when was the first time you sold a painting and realized you can maybe make a living at this? You know, ‘cause I think she was a yoga teacher and something else. And she said that somebody knew about her work and said, I have a friend who might be interested. And I said, well, how did you put a price tag on it? And she said, well, I basically went to some stores, you know, ‘cause they wanted something over their couch. And so what does an artist charge for a painting that size? You know, an unknown artist at that time, she said, I figured I could maybe get, I think it was like, uh, I don't remember the number for sure, but around like a thousand or $500, not a lot of money.

And I said, so when you were going to tell the person the price, how did you feel? She said, I was scared. Because I wanted to sell my art, but I didn't know how to price it. And so I used that as a gauge. I think it was like something like $1,500 she sold it for. And that was 10 or 12 years ago before this interview took place. And I said, so how did she respond? She bought it right away. And I thought, oh, I could have gotten more. She bit quick. And I said, and what would that painting sell for now? And she said, she smiled and said, $100,000. And so I know when I was videoing shows, I knew that I had a cost of the crews and the equipment, and I had a certain baseline I knew I had to cover. And then I had to make a markup over that so I could make a profit.

This was when I was operating my business out of my home. I would go for meetings with Halston, who was arguably the top American designer and most influential at that time. And my second client was Ralph Lauren. And I would say, I've got, I'm sorry, I have to get to another meeting. And that other meeting was with the unemployment office. So I could get my check, you know, because I couldn't afford to not get that at that point. You know, fortunately, pretty rapidly, I got past that. But that was for a while. I mean, that was some months. I didn't want to give that up, but you know, so I have certain numbers to go by. You, like this artist, were basically selling your time. And so that's why I wondered.

Dan Sullivan: You were selling your confidence, actually.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, yes.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. I mean, we all at the beginning, that's what we sell is our confidence.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. No, that's a great point. But I'm just curious because I think that's a problem a lot of people have is, you know, especially starting out, how much am I worth? you know, how much you're gonna get for this. And so you don't want to screw up getting a deal because you priced yourself out. You also don't want to short sell yourself. And you aren't even at the point where it's go to what scares you than 20% more, because you don't even know what that everything scares you. How do you overcome that hump?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, well, it's fair. Yeah, I mean, it's courage. You know, people who are courageous have a double payment, what I've noticed, that they get paid. In most cases, they get paid twice, but they always get paid at least once. And it's that they consider instructive learning a payment. So say the person says no, but you set it up so that you actually learn something from the no. Our sales team—and Coach is probably around 15—we probably have about 15. When they start off, they're on straight salary for the first year because they're just gonna have to get out there. And we still make a living from them if we're paying them 40,000 and they're bringing in 80,000, then we're still getting paid for it.

But our top salesman has been with us for about 15 years. Last August, he had a $50,000 a month. So, you know, you have a big divide. But the thing that I always tell the salespeople is that yeses reward you, noes teach you, and maybes kill you. Every day, the first thing you do is get rid of any maybes that you're going to talk to that day. Just talk to yeses or noes. And that's a very clean experience, okay? Therefore, you have to ask for the check right away. And the top salesman we ever had was a woman. She was having children, so she had about a two-year-old and a four-year-old. And she had 243 sales one year. She put 243 people into the Program. And she had some really devastatingly simplified lines.

She said, we talked about a month ago, and you said you were really interested. And so I'm going to ask you again, is this when you sign up? Because if you don't sign up, I'm not going to call you anymore. So let me know, let me know. And the person says, well, yeah, you know, but give me another month. She said, no, you've already had your month. You don't get another month. So yes or no. And she'd cross them off the list. A lot of salespeople wouldn't have that kind of courage because they take consolation in their maybe list.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, you're right.

Dan Sullivan: Just don't have a maybe list. Just have yeses and noes.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, and find out quickly. I mean, a lot of people don't understand, and you put it really well, that you're better off getting a no than another maybe.

Dan Sullivan: Oh, yeah. We had real scrutiny about call records, you know, because every time they make a call, there's a record of it electronically. And all of a sudden we discovered that over a five-year period, this salesperson, she had called somebody 60 times. And there were 60 conversations. So she was let go because she really wasn't doing it. But I talked to her and I said, I don't know what you were doing on those calls, but he was having an affair. Who talks to somebody 60 times in their head? And that was a nice, comforting female voice, you know, in the middle of the day. It's kind of a neat thing.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. Well, but you're right. You're right. When I started off on the play, in raising money, it was interesting because I knew that I had to channel my younger self. In my production business, at a certain point, I wasn't really having to sell myself that much. I had the work that you could look at, the clients you could see, and that kind of thing. Back when I was still designing clothes, and it reminded me because of this maybe story, you know, that you were telling, which I liked that a lot. And there was a guy based in Atlanta, wealthy real estate developer. And me and this woman that were starting this company, we had had four or five meetings with him. And then he wanted to, you know, meet in Atlanta where he was based.

We go to Atlanta and we meet, and then he says, okay, well, I'll get back to you, I need to think about this. And I said, no. He said, what do you mean no? And I said, you've got until I walk out the door. And you're either in or out, there's nothing more you're gonna learn. You know who we are, you know what the product is, you know what we're doing. And I don't have any more time to spend to explain to you because there's nothing new to tell you. This is it. And he's like stunned. And the woman I was with is also stunned. So I get up and he goes, where are you going? I said, we're done here. I told you, I'm walking out the door. And when that door shuts, this deal's done. So I need a yes or a no from you.

I got up and she started to say, you know, I'm sorry. And I said, Doris, be quiet. Let's go. He's not serious. If he's serious, he'll make his move. So we get up and he's just looking at me. And then I opened the door, let her go out first. I start to close the door and he goes, wait a minute. He actually ended up putting in the money. And I thought, you know, I was that aggressive when I was younger and willing. And I thought it really hit me vividly that I've got to start channeling my younger self and putting across that kind of in a way, I guess it's an ultimate, I don't like ultimatums, I don't like getting them, but it's like the old shit or get off the pot thing and don't waste your time. As you said, eliminate the maybes. It's a yes or a no and you move on.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. The big thing is that what's at stake there is your future confidence.

Jeffrey Madoff: You're right. That's a great insight. You're correct.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. You put up with that and you say, go to another meeting. You've just destroyed half of your confidence. And he knows it. You know, he knows that that's how he does things.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. You know, my thing is I love Lloyd Price's statement, which was the sure way to make sure nothing happens is to do nothing. So sometimes you really have to motivate the action. And sometimes motivating that action is taking a tough stand and setting the timer. You're in or you're out, we don't need to have any more meetings. So, yeah, and it's not easy to do.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, well, anything worthwhile isn't easy to do.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, that's right. That's right. So circling back to then wealth, I guess one can have a, well, I do think when you mentioned relationships, to me, that's a true currency in life, without a doubt. And then I have what I call my 4 a.m. friends. Who could I call if things really get tough and I need to talk, do I have anybody that I could actually talk to aside from my wife? And the answer is, fortunately, yes, I do. And I have always had that. And that's something, again, that my parents modeled and they had lifelong friendships and very deep friendships. And I think that the importance of relationships when they're only transactional with people, those are transactional relationships by definition. That's not gonna carry you through tough times.

So I think that that's really important. So I think wealth comes in a lot of different kinds of packages. And when you're just talking about money, you gotta look at the full picture, because if you're putting out a lot more than you're taking in, you're not wealthy no matter how big the number is. You dig in a deeper hole for yourself. And I guess that wealth is feeling a certain, the value of those relationships and being in the financial position to be able to afford to say no. I don't wanna do that. I don't care how much you're offering me.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, you know, I wrote one of my little quarterly books about two years ago. It was called You Are Not A Computer. And it relates to what a lot of the tech people say, you know, all the human brain is, is an information processor. That's all the human brain does. And computers now are faster at processing information than the human brain—which isn't true, by the way, but they define information in a certain way so that it is true. And I said, well, that isn't what humans do at all. I mean, we have that as an ability, but that's not really who we are.

What we are is meaning makers. We take our experiences and we create meaning out of our experiences. And therefore, if you're the one who's creating your experiences, make sure that you're winning. So that when you walked out and would have closed the door, you were going to be the winner, whatever, if you walked out, I mean, he caught you a few seconds before the door closed. But if you had closed the door and walked out, the money that you perhaps lost was minor to what you just did for your own meaning about who you are.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I mean, in retrospect, I hear what you're saying and agree. At that time, my thing was, it's kind of like enough's enough. There's nothing else I can tell you. That's it.

Dan Sullivan: But that builds character.

Jeffrey Madoff: I like to think so. I mean, I realize you can die from building character, but that’s why Wild Bill Hickok had to sit in the corner of the bar.

Dan Sullivan: Realizing that, but I don't think you like who you are without building character, you know?

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, I think that's true. And character has to be put to tests because life will test you. And it's how you respond to those challenges that I think are most significant. I'm a big believer in race under pressure. And, you know, how do you behave when things aren't good? And we've all been on our rollercoaster rides of that. And the thing is that I think if you are ashamed of those things that didn't work out, you have to look at the bigger picture. And like what you were saying, that moment was another building block of my confidence. And you deciding to make the leap into starting Coach, I remember the first time that I interviewed you at Joe Polish's session, we talked about pricing. Do you remember that?

Dan Sullivan: I remember the interview. I don't remember that part of the interview.

Jeffrey Madoff: That part of the interview when I was asking you, how do you know what to charge? And you kind of smiled and sat there a moment and said, wait a minute, I haven't thought about that before. And then you said, do you know the way to determine what you charge? And you said the same thing you had said before, what scares you plus 20%.

Dan Sullivan: And you have the 20% because if the other person says, okay, you kick yourself for not asking for it.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. But then you also have to deliver on the promise.

Dan Sullivan: Sure. Yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: Otherwise, you're just a con.

Dan Sullivan: You know, if you think about it, you think about your students at Parsons, and you think about people you've known in the entrepreneurial world who are really successful, that the number one capability that separates those people, let's say they're students, and they're there essentially looking to develop a creative career. As it turns out, they don't. They just go to work for somebody. The biggest thing between them and the person sitting next to them who goes out and has a successful creative career and them being an employee is the one of them has the capability of understanding pricing in the marketplace and the other one doesn't. And then people who are really good really understand pricing in the marketplace.

Jeffrey Madoff: Oh, you're right. You're right, because that's a necessary survival skill. So what do we come at, at this point in terms of?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, well, I think we expanded on the concept of what wealth is and that people who have only financial wealth have no wealth at all.

Jeffrey Madoff: And without the context of what that means, which is, you know, in a sense, your life is a business. If you constantly have more going out than coming in, like a business, you can go bankrupt.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: That was good. That was good. I like this. Yeah, it's really interesting because I do think that emotional wealth, relationship wealth, ultimately will lead to a greater sense of purpose and satisfaction.

Dan Sullivan: And you'll make the money.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. Yeah. Well, this is certainly anything and everything.

Dan Sullivan: Yes, I think we always worried that we're not going to obey the rules, but we did.

Jeffrey Madoff: Thanks for joining us today on our show, Anything and Everything. If you enjoyed it, please share it with a friend. For more about me and my work, visit acreativecareer.com and madoffproductions.com. To learn more about Dan and Strategic Coach, visit strategiccoach.com.

Related Content

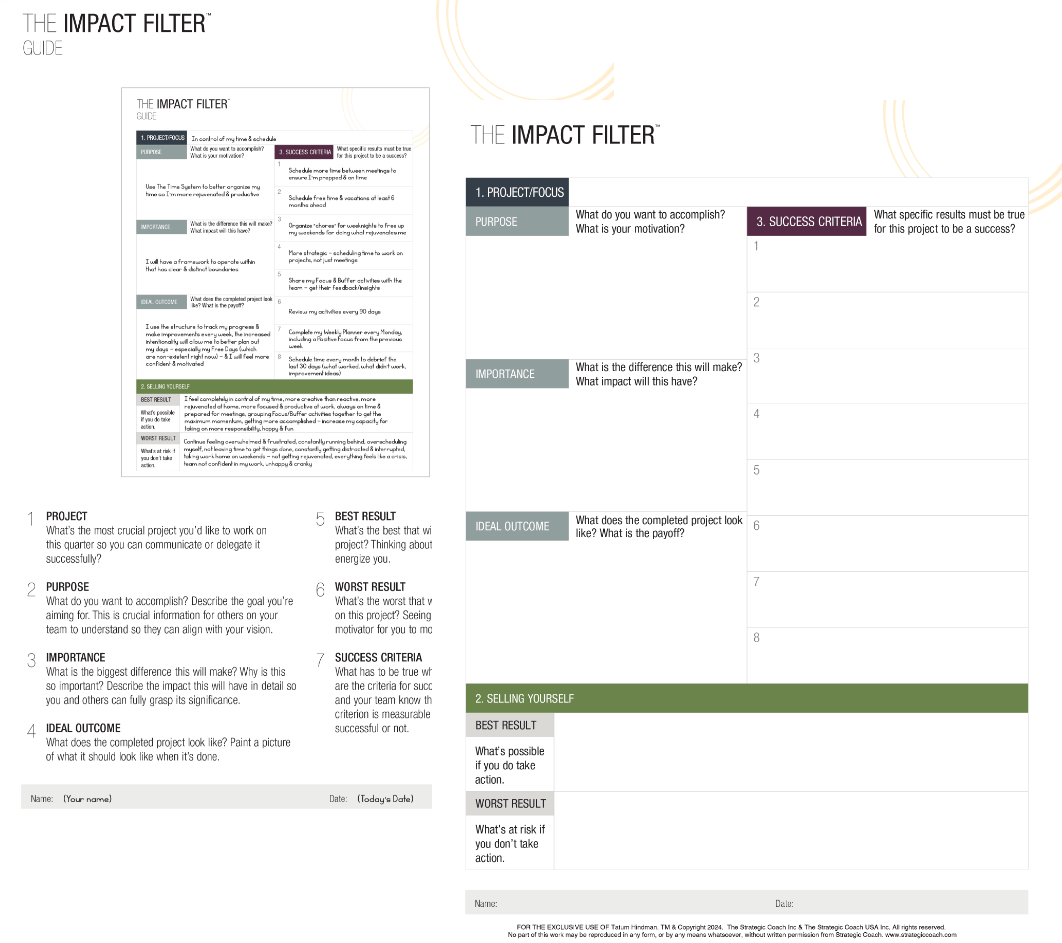

The Impact Filter

Dan Sullivan’s #1 Thinking Tool

Are you tired of feeling overwhelmed by your goals? The Impact Filter™ is a powerful planning tool that can help you find clarity and focus. It’s a thinking process that filters out everything except the impact you want to have, and it’s the same tool that Dan Sullivan uses in every meeting.