Bridging The Creative-Business Divide

May 14, 2024

Hosted By

Dan Sullivan

Dan Sullivan

Jeffrey Madoff

Jeffrey Madoff

Jeffrey and Dan dive deep into creativity, innovation, and the intricate dance between good business and exciting innovation. Inspired by Dan's quarterly book, Everything Is Created Backward, they discuss how integrating existing technologies and ideas to create something entirely new can completely disrupt the market and lead to record-breaking profit.

In This Episode:

- There’s a permanent tension between creative people and organizational people (business executives).

- Most creative people are not good organizational people.

- Creatives are focused on innovation, while executives are focused on finances and risk aversion—and furthering their careers.

- This approach often stifles innovation.

- Creatives are also subject to immediate public scrutiny. Their work is usually under the critical eye of audiences and critics.

- Executives, by contrast, are evaluated based on stock market performance and long-term organizational success. Their reviews are reflected in corporate outcomes.

- Successful partnerships, like that of Brian Grazer and Ron Howard, showcase how creative and organizational individuals can collaborate effectively to create engaging content.

- In order to bridge the gap, creatives need to better package their ideas to highlight the business potential to financially-minded decision makers.

- Businesses, on the other hand, need to be more open to creative, potentially risky ideas that could pay off big time.

- Recognizing your core business focus is what drives long-term success.

- Major business innovations often come from combining three existing components in a new way rather than from creating something entirely new from scratch.

- Large companies sometimes buy promising start-ups, not to integrate their innovation, but to shut down potential future competition.

Resources:

Personality: The Lloyd Price Musical

Learn more about Jeffrey Madoff

Episode Transcript

Jeffrey Madoff: This is Jeffrey Madoff and welcome to our podcast called Anything and Everything with my partner, Dan Sullivan. Well, you know, Dan, you were starting to talk and immediately we were getting to something that we wanted to talk about in the podcast. So why don't you kick us off of what you were saying in terms of creativity?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I write quarterly books, and I've been doing this, this will be my 38th book in 38 quarters. And the name of the book is Everything Is Created Backward, which is not immediately obvious. And what I mean by that, and I use the example of Steve Jobs creating iTunes, that what Steve Jobs did, first of all, he was fired from Apple and there's a long story there, but I won't get into that. But while he was away from the company, he got really interested in music and he made an observation that in those days, this was in the ‘90s, and he made an observation that when he tried to get a song that he really liked, in order to get the song he wanted, he had to buy 10 others or 11 others because it only came on an album. And he said, you know, this is really weird. So I'm a composer, and I got a great song. And in order to get my great song out to the audience, I have to come up with 10 other songs. This is where 45 RPM had an example. You only had to come up with one other song to get it recorded. But by the time you got to the ‘90s with albums, you had to do 10. And he said, not only that, but I looked into how much money the artists make. If they're lucky, they get a nickel and a dollar of the final cost. And he says, I bet they're paying for a lot of accountants, lawyers, and bureaucrats to get the music out. So he came back and he did one of his very famous introductions of something new. And they were famous because the entire investment world stopped, the entire technology world stopped. And he'd come out and he'd talk at an experience. So he tells his personal experience about his frustration. And he said, you know, actually there's some things already out there that if we put them together in a new way, we can produce something that I think people would like. He says, first of all, MP3 players are now really popular. People really like the mp3 player because they can download from their computer, they can download into their mp3 player, but they pretty well have to download albums from their computer operating system. And he said, so that's one thing that we already know the mp3 players work and we have millions who've already purchased the iPod. And, you know, it's better than all the other mp3 players. And he says, and I was getting really interested, but there's already a company out there that's downloading single songs from the Internet. And it's called Napster. And Napster is people who nap things. They steal things. And so if you get in touch with Napster, they'll steal for you. And that can't last too long. As a matter of fact, there's already lawsuits, and they're going to get closed down. But they had a good idea. And the internet is just getting filled up with songs. And because they're digital, you can isolate each song, and you can download it. And we've got an operating system with Apple computers, and we have 20 million people who are using the Mac operating system. So I said, why don't we, first of all, make it legal? You can download a song on our Apple platform for a dollar. It just costs you a dollar for a song. And by the way, we've figured out that the artists should get a lot of money. So we're offering all the artists, if you put it on our new thing that I'm going to tell you about here, if we get a dollar, you get 60 cents of the dollar. We think that's a better deal. And then you can just download it to your mp3 player and since you're already using the Apple platform you might as well have an iPod but we call this new thing iTunes does this and everything like that so we think that probably a lot of artists in the world would like to put their songs in such a way that they can be downloaded to the Apple platform and then downloaded to the iPod, you know, kind of makes sense, you know, cuts down on the complexity. And by the way, this is available as soon as I finished my talk. And that was iTunes, you know, one thing I'd like to make about this, he was just using existing things. But the record shows that it's usually three things that get combined to create a new thing. And there's lots of history, the telegraph, the electrification of cities. Edison invented the light bulb about 40 years after it was invented. He didn't become famous because he invented the light bulb, he got famous because with a click of the switch, he had a 12-block by 12-block section of New York City that all you had to do was press a button and all the lights came on. That's why he got really famous and rich. So the name of the book, again, is Everything Is Created Backward. Namely, you're not creating things out of an imaginary future. You're simply taking things that exist, but they're not connected with each other, and you just combine them to create something new. Not everything works. But if you have some sense of where the market is and what the market would like, and you create three things that are already in play and put them together in a new way, then you might get a real breakthrough.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, there's a number of things that are really interesting about that. With Sony, Akio Morita, who is a visionary, of Sony, who I actually met, and I worked with his wife in Paris. They already had computers. They had hard drives, you know, for the MP3s. They had a music company, Sony Music, and they had content. They even had Sony Pictures, but there was nobody there to put it together like what you're talking about. So a hugely missed opportunity because Apple still had the licensed music and Sony already had quite a substantial catalog at that time. So it's really interesting how two people can be looking at the same thing and one person sees a tremendous opportunity and it doesn't even get the other person's attention, which is quite fascinating. And you would think, because a precursor to that was the Walkman.

Dan Sullivan: Which was dynamite. Yeah, yes. I remember my first Walkman. I couldn't believe how good it was.

Jeffrey Madoff: I was given my Walkman by Merida, was chosen to direct the French collections back in like 1981 or something like that. It was really quite interesting because they gave the Walkman, the term wasn't used then, but to who they thought were influencers. Because you travel around Paris to go to the different venues for the shows. So, everybody's saying, what are you listening to? You know, because people were for the first time walking around with headphones on. So the portable personal music player that they had all the components for, including content which Apple didn't have at that time, and they totally missed the boat. And part of that was because I think the visionary, the person who understood these things, Akio Morita, was no longer there. Yeah, by the time we got he was there for the Walkman and he launched it.

Dan Sullivan: I'm talking about in terms of, yeah, if you look back, Sony was going like this and then they leveled off when they missed that opportunity.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, it's really fascinating. And when you talk about using old things, what Edison did was instead of running new power lines, he put them through the gas pipes, because that's what all the streetlights were. And so he used something that already existed. That was really the brilliance of it, because he could do it faster than anybody else. which was really interesting. So your thesis about putting those old things together is really, really interesting. And I think it brings me to the question of, there's always seems to be an adversarial relationship between creativity and the business side. I mean, jobs really manifest that, when they got rid of them and then realized they had to bring them back. So how do you look at that?

Dan Sullivan: It's very interesting. I'm sort of collaborating. It'll be his book and his idea. And I have a 29-year-old in the Program right now who's actually been exploring artificial intelligence for 10 years, since he was 19. We actually had him into our company. We have 130 team members, and he's created a very nifty six-module Zoom program, two hours. They're about two weeks apart from each other. And what he does, he just first of all gets over the fear of AI, because people hear a lot of stuff. He just focused on what are you doing already that is probably repetitive and you don't really like doing it, but if you used an app, which they are app and AI app, it could cut off 10 hours of work per week. So if each of you, every two weeks, cut off 10 hours of certain activity or two hours here, maybe by the time we get our six sessions done, you could have freed up 20 hours per week, which you can now devote to things you really love doing. Okay, and taking the stuff you're really good at and having more time for it. And that's his whole thesis. He just gets you, how do you improve productivity in a company using readily available AI programs? Okay, so he wrote a book called AI As Your Teammate, and we gave it out to everybody. We gave it out to all of our clients, and he's thriving. You know, he's really thriving because Coach people with the Who Not How concept, your Who may be human, but your Who may be technological. Okay. I'm a hybrid there. I believe in the technology, but I also believe of having a smart human between me and the technology. So anyway, we were talking about his next book, and he wants to talk about the exponential power of what he's observing, because he's got many, many different examples of different companies using it. And he said, you know, you can't really, really figure out an exponential future, unless you're creating human AI teamwork. Okay, so that's his whole thesis. And he's searching for titles. And I'm good at titles. You know, I'm, I'm an old copywriter. And If you don't have the title, you don't have anything in the ad business. If you don't have a headline, you're dead. So I said, you know what I would call it? I would call it exponential tinkering. And he says, gee, I really like that. And then we started talking about tinkering. And tinkering is a creative process where you're just doing it for the hell of it. You're just taking this together and putting it together with this, and you're kind of doing it for personal satisfaction. And every once in a while, you show what you've done and you've shown it to somebody else and say, how can I do that? And then you're off to the races from a possible business. Steve Jobs was a tinkerer. Morita, he was a tinkerer, too, because I think they started off in the bicycle business or something, didn't they, Morita? You know, pre-World War II, and, you know, they were just hustling. They were just hustling like all Japanese were after the war, just to get back out of the hole and the level ground. Morita was a real tinkerer, but he gave a talk to the Harvard Business School, and the question came up. Of course, Japan was really on the ascendant, so he's talking in the 1970s. You know, there were movies out how Japan is taking over the 21st century, you know, and all this. I think there was a Sean Connery film, you know, about the Japanese, how smart they were, and they were just eating the United States breakfast, lunch, and dinner. And he was asked the question, will Japanese ever be as creative as Americans? And he said, no. It was Harvard, you know. And they said, well, why? And he says, no garages and basements.

Jeffrey Madoff: No place to tinker.

Dan Sullivan: And he says, kids are not allowed to be on their own. They're expected to be a member of a group. OK. And he says, you can't tinker if you're a member of a group. You can only tinker on your own, and it's gotta be encouraged and it's gotta be rewarded. He says America rewards unique people to be on their own and tinker.

Jeffrey Madoff: You know, it's interesting because we grew up at a time …

Dan Sullivan: People who run companies are not tinkerers. What are they? They've got an objective, they've got quarterly results. They're very, very tightly focused on a very narrow set of objectives. And anything that looks like tinkering doesn't fit in with what's profitable right now.

Jeffrey Madoff: You know what that makes me think of, and you're right, is when Xerox created Xerox PARC, which was some of the most innovative things happening in technology, creating the Ethernet connection. Graphic user interface. Yes, that Apple copied and sold. Well, that was the famous lawsuit that Jobs sued Microsoft. And it was probably one of the only funny things that Bill Gates has ever said. Yeah, when he said, how could we steal this from you? You stole it from Xerox. And yeah, it's fascinating. That's a great example of it because they had some of the greatest minds in the world tinkering, if you will. And back in New York, well, I don't know what they're doing and we're spending too much money on it.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Well, Kodak invented the electronic camera. Right. Okay. And you can just see the guy showing up for the board of directors meeting where he said, what's the point of this electronic camera? And he says, well, you won't have to have film anymore. 90% of their profits were coming from film.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. And the interesting thing is that they thought they were in the business of selling film. And they weren't. They were in the business of capturing memories. And experiences. That's right. One of the great campaigns of all time was the Kodak moment. And it was fabulous. And who cares whether it was digitally captured or on film, but they cared that it was on film. And I had breakfast this past week with a person who you see, one of the marketing heads of Eastman Kodak, we were talking about, they had a group that was working on a digital image capture. But all the entrenched minds thought, no, that's not going to work. We're in the film business. And he kept saying, no, we're not. We're in the memory business. You know, and it's so fascinating.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. And that may be my former … that's correct. Very interesting. There are a number of experiences that are converging here. One of our clients, longtime, 26, 27 years in Coach, his wife was an IP lawyer. And for about 10, 12 years, she was the IP lawyer for Kodak. And over those 12 years, the only profit center of Kodak was her licensing, the buildup of immense intellectual property over 100 years, 100 and whatever the entire history of Kodak is. I don't know how far they go back. And they just have thousands and thousands and thousands of patents. And her job was to be a hard ass with the patents. You don't use our stuff, you buy our stuff. Okay, and we have very tight restrictions and under what circumstances you can buy it and what our relationship is going to be in future and she was the profit center for a dozen years.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, it's interesting because I didn't know until that breakfast. I didn't realize that what Kodak really dominates now is printing business and the technology that they had developed for that, but they're nowhere near the business they used to be. No.

Dan Sullivan: And they have, you know, high level industrial photography, for example, the best body composition machine, you know, it photographs you, it videos you 3D, you know, and it shows you what's fat and what's bone and what's muscle, you know, it shows everything. It's the state of the art and it's a Kodak machine. So I think that they've gone into the back stage of a lot of industrial manufacturing corporate and they're creating very specialized applications using their vast intellectual capital that they've developed over the years. But the iPhone owns the capturing memories work.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, that's right. But actually, Kodak has a part in every iPhone.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, they're paying. They're paying them.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. And that's what's so interesting.

Dan Sullivan: When your lawyers are your profit center, you're not innovating.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. Now, what Kodak does do and makes money at is licensing their technology, like they do to Apple. I mean, nobody really knows about this. Not that it's any big secret, except as you said, it's more of the back stage business.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. You know, to a certain extent, it addresses the question that you ask, why is there an adversarial relationship between the creative department and the business department? You know, it's not always true. Sometimes there's a great relationship and those are very profitable companies. Yeah, once they find it sells. Yeah, it was very interesting. I read the history of the iPhone and Steve Jobs was totally against the iPhone. The argument that turned him in favor of the iPhone is that the head of the design team of the iPhone came and showed it to him and he says, we can't do it. It'll kill the iPod. And the man said, well, somebody is going to kill the iPod. It's your choice who you want it to be. He said, this will kill the iPod. But if anybody kills the iPod, it might as well be you. He says, OK, let's go with it.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, it's interesting to me that I straddle both sides, being the lead producer on my play and also the playwright. So I fight with myself all the time.

Dan Sullivan: It doesn't show. Your internal conflicts don't show on the outside.

Jeffrey Madoff: And so I always wondered, and this goes back long before I started doing what I'm doing now, why is there the so-called suits on one side and the creatives on the other? And that's in the music business, it's in the movie business, it's in the technology business. Why is that as opposed to what makes the most sense? Let's work together to create new opportunities and new products because that's how we're going to innovate and grow.

Dan Sullivan: Well, as you propose the challenge for the podcast today, I was thinking, using yourself as an example, is that you're very creative, but you can also count. And it's the separation between innovating and counting that causes the tension. I mean, a lot of suits, they're suits because they can only count. They have no other chip in their brain except the counting chip. Okay. And part of the counting is what does this do to my career? And it's easier to say no than it is to say yes to something new. I mean, that's right. The other thing is creative people often don't know how to package their creativity in such a way that the counters can see the future prospects.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, considering that it's in everybody's best interest, the business's best interest, to work together, how do we best package this and bring it to market? How do we support it? You know, innovation which, you know, is it a lull now at Apple, for instance? You know, and AI has taken over the attention of anybody interested in tech at this point. That's the new, new thing, the new shiny keys, whatever. But how do you create a bridge between that creative desire and the business where it's not adversarial?

Dan Sullivan: Well, I think probably if you look at the history of companies and where they start is because the creator is the first CEO and they create the bridges to the counters. I don't think counters ever create a bridge to the creative. They'd have to be creative in order to create a bridge to the creativity. I think that the counters are an after-the-fact addition to the idea, the new idea. I mean, you can look at all of them. Edison became a huge corporation, but he wasn't the CEO after a certain while. There was a certain point where they stopped innovating because they established monopolies, and all you have to do is discourage the competitors. Which Bell Telephone was huge at doing. AT&T, you know what I mean? AT&T. I mean, people talk about the monoliths today, like Meta and Google. They couldn't hold a candle to AT&T at its height. AT&T puts standard oil in the shadow.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, because no matter how benign or small your product was, if it touched theirs in any way, they'd sue you. And they had the money to do it.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Their lawyers made more money than your company makes. That's right.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. Yeah. But how do we encourage collaborations where it's not adversarial. I mean, it's interesting with the SAG and the Writers Guild Strike, WGA, nobody goes to the movies because Disney has got a great accounting team. That's not why you go to the movies. Teaching at the New School, as I did, nobody goes to a college because, wow, they have a really good administration. They go because the front stage are the professors and the courses that are offered. So there's a schism like labor and management. There's a schism with faculty and administration. And I'm wondering, how do we knock down those barriers? You don't.

Dan Sullivan: You don't. And why? Just create something new and create a business model around it.

Jeffrey Madoff: So you're saying, if you're at that company, leave that company, take your idea and do it yourself and become an entrepreneur.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Yeah, I remember it was the fall of ‘22 during COVID and all the big tech companies over a six month period laid off about 300,000 employees. Microsoft, Apple, the big five, you know, the big five, including Amazon. And I was talking to somebody who's kind of knowledgeable about the tech business, and he said, you have to understand that the big tech companies scoop up talent whether they have any reason for it right now at all. And he said, so a lot of the hires they've done in the previous five years before this layoff, they were just hiring people so that their competitor didn't get these people. And they put them on 10-year projects. Not anything they're making any money on, okay? They're not making any money on this, but you never know. They may come up with something new, and when the time comes, we'll have something new down the road. But the restrained forces in the marketplace that they could see coming, and they've gotten really restrained, they started firing the 10-year people, the five-year people, and they came down to the next two-year people, and let's keep the next two-year people. Okay. And these are the counters. The counters told them to do that. Yeah, but they're working as a, you know, they're not making us any money. We've got to report to Wall Street every 90 days and that's not going to do us any good, but they'll vote us up if we slim down.

Jeffrey Madoff: But does that really happen? What's the real cost of that? What's the real cost of stopping the innovation?

Dan Sullivan: Well, out of the 300,000 they let off, about 30,000 of them are going to become their competitors over the next 10 years. I mentioned at the beginning Perplexity, which is an AI app. It's a neat thing. I highly recommend it. If you haven't dabbled in AI, just go to Perplexity. Interestingly, I go to Google and I punch it in and it comes up. Evan Ryan, who's my 29-year-old, he's the only client I have that I'm 50 years older than. I just find him very intriguing. His experience and how he's looking at the world is very different than how I was looking at the world in 1973, 1974. So he said, I always Googled things, you know, to see it. And he said, for the last four months, I've been just using Perplexity. I get better answers from Perplexity. And they do some thinking for me, you know. So, where this all started, there's a guy who probably lives a mile from you in New York. His name is Mark Mills. He's a featured writer at the Manhattan Institute, which is a free market technology-focused research organization. And he wrote a book called The Cloud Revolution. And that's where he brought it up. And he gave about 10, 15 examples of the combining three technologies to create a breakthrough. So this is not my idea. This has been commented on previously. It's just that I came up with a really sexy headline, everything is created backward, which it's a compelling offer, it's not a convincing argument. You don't sell convincing arguments, you only sell compelling offers. I looked it up and I said, Mark Mills, in the book Cloud Revolution, explains why breakthroughs happen as a result of combining three breakthroughs. And I get about five, six paragraphs. And then down below, it says, you might look at these three aspects. And then you punch out that aspect, and you get another six things. And at the bottom of that, there's three more. You might look at this as a result. So it's responding to the direction that your interest is going. But at the top, each one, it gives you four references of books where this is mentioned. And you can punch on them, and then they'll explain what that book says. Google doesn't do that for me. So my sense is that they're the biggest search engine in the world, and they're the biggest advertising platform in the world. They're bigger than Meta now of Facebook. They're the biggest last year. But it depends upon having people who go to Google all the time. So let's say Perplexity takes away 2% of their audience. And then another AI program does something else that takes away 2%. Pretty well, the counters are gonna start shouting.

Jeffrey Madoff: True, true. What is it, though, about creativity that creates the perception of outsized risk? It's disruptive. So let's go into that a little bit deeper. Because you can't keep returning to clients to sell the same thing over and over again either, right?

Dan Sullivan: There's a danger to same old, same old. There's a real danger to that.

Jeffrey Madoff: I mean, you know, you have to give people a reason to buy.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. And if they're starting to get tired of your offering, they go looking.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right.

Dan Sullivan: That's right. There was a very influential book called The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, I think written in the 1960s by a man by the name of Thomas Kuhn, K-U-H-N. He said, everybody thinks that science sort of develops incrementally with a lot of agreement and a lot of teamwork. And he said, as far as I can tell, none of that's true. It's highly political. It's viciously competitive. And he said, old people control the funding. So someone asked him, I saw a little clip where he was being interviewed and he says, what causes sudden scientific breakthroughs? And he says, the funerals of old scientists. He said they control promotion, they control funding, they control the publications, and he said when they die, it creates room for younger people to come along.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, you know, a way for people to die, metaphorically, is to allow themselves to get bought by a large company, like the hires that you were talking about. Dennis Crowley, he invented Foursquare, which is very popular in Europe, not as popular here, but it's quite successful. And it was one of the first geosocial networking apps. Prior to that, his first company was, I think it was called Volleyball. He got bought by Google, not for the astronomical funds that started happening in the 2000s, but, you know, pretty good amount of money. And what happened was two years into it, they shut it down. Dennis told me he went into a deep depression. He taught snowboarding for one or two years. Very emotional. That's very emotional. Well, because what happened that first seemed like good news, we've got a big company behind us is going to help finance this innovation. It's going to go. Google knew they were going in that direction. And so they bought up companies that were potential competition to them. Pharmaceutical companies do it all the time, so they don't have to put the money in the R&D. And Dennis said, they bought us to kill us. And he said, I was too naive to realize what that was. There was nothing that we could have done that wouldn't have prevented them from killing us. That's why they bought us. They were afraid of what we were doing.

Dan Sullivan: That's why Facebook bought Instagram. But Instagram's become their big moneymaker. Interestingly, yes. But originally, that's not why I called Facebook. Meta just doesn't give me any handle. But Facebook gives me a handle.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, there was a company that was all the rage for a little while. There was Meerkat and Periscope. And these were how you could live stream, you could become your own entity by live streaming your reviews or reporting. It was going to revolutionize everything. Twitter, and I may have the two companies confused, I can't remember which bought which, but I think it was Twitter bought Meerkat. And they talked about how this was going to be the future of how people communicate, the future of how news is reported, all this sort of stuff. What they did is they bought it so that all the experimentation would be under that name. And as soon as they thought they actually had something, they killed that company. So that they didn't soil their brand with the parts that didn't work as they were developing it. And it was really fascinating. So, so many times we see, let's call them the suits again, do things that try to stifle competition, stifle innovation, and ultimately, those companies that let that go, like we saw with Apple and so on, prosper greatly. Now we're seeing that with AI companies like Perplexity. Certainly, look at the life that ChatGPT gave Microsoft. Who thought about Microsoft anymore? You know, so it's quite fascinating. There's so many examples of creative innovation just becoming a waterfall of money at a certain point.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, but I think there's levels of creativity at all areas of human organizations. So I think that at the very top level of corporate people, there's a kind of creativity that can't be seen, but it's manipulating in the corporate marketplace. You know, and I think that Musk is unusual because I think he's good at both sides. So much so that I think that he is actually the stock, the valuation of Tesla, because he groups everything under Tesla, like SpaceX is under Tesla and has solar company is under Tesla. I mean, Tesla, just on the basis of how much cars they produce, shouldn't be valued what it is. But I think he's very gifted at a number of things. One is that he's a reality distorter like Steve Jobs was. I mean, you listen to him for about a half hour and you say, oh my god, I'm going to get a second mortgage and give him all my money. Because he has great certainty about the future that it's not possible for anyone to have. But I think he's gifted at both sides. He kind of understands where the money comes from. He understands how you get your valuation up. But he's an extraordinarily good engineer. Apparently, people who know him says he's a very gifted engineer. And he understands how to get things really simple. He understands how to get rid of that, get rid of that, and get rid of that. And that's a form of creativity. I mean, Tesla is not his invention. He was just an early investor in Tesla. In the way that other investors get taken out, he took them out and it became his thing. But I think SpaceX is really his thing he'll be remembered for because he's reduced the cost of rocket launches by 90%.

Jeffrey Madoff: If you were given a choice of who to invest in, would you invest with Warren Buffett or would you invest with Elon Musk?

Dan Sullivan: Warren Buffett.

Jeffrey Madoff: Me too. Why?

Dan Sullivan: Well, he's got some criteria about who he invests in. He looks down the road 20 years and said, will the customer for this be bigger 20 years from now? For example, when he invested in Gillette and he said, will there be more men? Yes. Will there be more men shaving than there is today? It's good stock. Okay. He's got some other behind the scenes criteria. Do I trust the person? Do I admire the person? I think he invests in people before he invests in what they're invested in. I think he's a great people spotter. If I invest in you, do I have to worry about you? And if he has to worry at all, he doesn't invest.

Jeffrey Madoff: And I would say that that's exactly the spot that Musk is in. Because you gotta worry about him. Because you can send the stock cascading, and then it can spike back up again. But do you wanna have to deal with that erratic behavior when you're putting your money into something?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, and you can't plan long term with that type of person. You got to get a fairly fast and early return.

Jeffrey Madoff: So what we're also getting to, which is really interesting, is what attracts investment. So, you know, like Jobs, I don't think like Jobs, I think Jobs was a much more charismatic presenter than Musk. But, you know, as Jobs was inseparable from Apple, and then of course, as we've talked about in the past, you realize, well, Apple's gonna continue. And Tim Cook has done an incredible job of greatly increasing the value of Apple. How much is Musk inseparable from his company? There's no difference. And that's dangerous for a public company.

Dan Sullivan: The market valuation of Apple has gone up 10 times under Tim Cook. Yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: And you wouldn't call Tim Cook a charismatic leader like you would Jobs.

Dan Sullivan: No one would be accused of that.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. That's right.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, and he tried to be at the early, when he took over, he tried to do that. He wore the same costume and he had the same backdrop, but it just didn't work.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right, that's right. It's really interesting because oftentimes, I think what captures the imagination of potential investors is that charismatic personality, that how tethered they are to reality is another question.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. But and how much of it is an act? Elizabeth Holmes was. She copied Steve Jobs. She took voice lessons to have a deep voice. And she had the turtleneck and she had the sort of mystical delivery and everything else, except there was no truth to what she was doing. And you could tell by her board of directors, she didn't have one medical person on her board of directors. I mean, she's changing the medical world and she doesn't have anybody who's got a medical. She has secretaries of state, you know, Kissinger, she had, what's it, George, not as famous as Kissinger, George, I forget what his name was. Yeah, that's how famous he was.

Dan Sullivan: But Kissinger says, “I think this is a very important breakthrough.” Young people, you say, well, you know.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, then you just revealed another hidden talent. Your Unique Abilities, you know, keep growing.

Dan Sullivan: That was a good … listen to it. [In Kissinger voice] “You know, it reminds me of Herr Hitler. It's a wonderful thing.”

Jeffrey Madoff: So then we get to a phrase which I love and use, and it is the old guesses and bets.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, it's all guesses and bets. That's right. The future consists of two parts, guesses and bets. That's right. Yeah. No certainty. No certainty. No sure bets.

Jeffrey Madoff: And so when you're looking for somewhere to put your money, I mean, it's interesting that we both would go to Warren Buffett, not the charismatic leader who may just be a little too erratic and crazy, you know, to put your money into. I mean, you know, look at Adam Newman from WeWork, another very charismatic leader who was basically a con. He's the only one that actually made off with a ton of money and got out clean. I don't know how that's the more, even more interesting story, you know, because WeWork was basically, oh, you're a high-tech landlord. What is this business? It doesn't make sense. But these people attract lots of money. And again, it's all guesses and bets. But I think when somebody portrays themselves with so much confidence and they're so sold on themselves, like Elizabeth Holmes, I think people guess that they can bet on that one because, you know, look who they're attracting. I'm blanking on the secretary of state who invested with Elizabeth Holmes. And there are a bunch of, frankly, and I don't normally use this phrase, but old white men who are very attracted to this attractive, seemingly articulate blonde. And I think that they liked that whole attention. I think it gets pretty much back to the primate level.

Dan Sullivan: Well, you know, it's an attraction of older people to be in touch with the energy of young people. You know, I think it's kind of like that, you know, I understand it.

Jeffrey Madoff: Oh, I understand it. But fortunately, I wouldn't invest in it.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, but I think that when it's explained that we're taking something that already exists here, something that already exists here, we're putting it together in a new way. It gives you more grounding for saying, you know, this might work, this might work. But I was thinking of your play that a number of things came together that already existed. Lloyd Price and his history already existed, his music already existed, your ability to capture stories in writing and video already existed, and also live performance, because you did a lot of live events where people had to perform in a live sense, and you were doing it right in the epicenter of theatrical talent, you know, on the planet, with the exception of maybe London. But you were certainly in the epicenter of where theater can be capitalized. So you were putting a number of things together and, you know, you were relying on some people that you already knew to do the initial funding, you know, probably where you live within four miles of you is all the talent you were ever going to need both front stage and back stage to get the project rolling. So there was a lot of things that you just put together.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, and part of that reason is, first of all, I went to people whose talents I greatly respected, whose accomplishments I greatly respected. I knew that I had no name in that business, so I had to surround myself with as many of the best names as I could to establish that credibility.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. And you know, there's a reality to that because you were competing with other offers that they were getting at the same time.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, that's right. And, you know, as you said, and I agree, a compelling offer is better than a convincing argument in terms of closing a deal. So I think that the aggregation of these talents around this topic, which is still so highly relevant in our culture, all of these things, I think, you know, created an attractive bet. But the interesting thing is you never invest in an app, you know, thinking it's going to be fun. You're hoping that you're going to win the lottery. With a play, most people invest first and foremost for the journey. And if you make money, that's a huge plus, of course, mainly for me, because that means I can do this again, you know. But, you know, and I'm not comparing myself to him, but Stephen Sondheim had a lot of plays that did not make money. Yet I think that it is inarguable that he's one of the most significant figures in musical theater. So it's kind of interesting, but it really is guesses and bets when you're creating anything to do with the arts.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. But you know, in the spectrum of guesses and bets, there's people who are better guessers and better betters. That's right.

Jeffrey Madoff: You know, and you also at a certain point, not just sell the project, you sell the people who've invested in the project. Because that lends credibility, whether it's accurate or not. That lends credibility to it.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I mean, the interesting thing about it, one thing to bet on is a great story. Dean Jackson, who you know, Dean does movie reviews. He's got a digital audience that follows his advice. He's an aficionado. He really likes going to movies, and so he'll do one a week if new movies are coming out. Not all movies, but I remember with Napoleon, the movie Napoleon that just came out, he had the shortest review I've ever seen. He said, it's just a lot of middle. He said, it's either palace intrigue or it's a battle. And he says they do it six times over two hours. And I said, you know, Napoleon's a big subject. I would have done a trilogy. You know, you would have the young Napoleon from being a minor Corsican officer who basically restores order to Paris and France after the revolution, and that's movie number one. And movie number two is him being amazingly successful and becoming emperor of basically Europe. And then there's his decision to go into Russia. And through that is weaved the relationship with Josephine and all the other stuff. But it's worth probably six hours. It's not worth two hours, but it's worth six hours. Because each of them has a beginning, a middle, and an end. That would make for an interesting story. I mean, The Lord of the Rings would not be an interesting two-hour film. But it was a fascinating eight-hour trilogy.

Jeffrey Madoff: I never saw it.

Dan Sullivan: It was super. I'd read the book twice, actually. It got me through basic training in the army. Because your fatigue pocket, it fit perfectly in my fatigue pocket because reading involved paper when I was growing up. Lots of pages of paper. So what can we say about our conversation? What is it? I think that there's a permanent tension between creative and organizational people. Most creative people are not good organizational people.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, and the question is, where does that tension arise?

Dan Sullivan: They have completely different objectives.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right. That's right. And what would you say are those objectives?

Dan Sullivan: Well, I think for the creative, it's something new that's better than something that exists.

Jeffrey Madoff: I would couple that with it's about a compelling need to express and get your expression out there. You know, that kind of drive, because so often actors, musicians, dancers spend so many years making nothing. But they wouldn't trade what they're doing because they have a compelling need to do it.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, they die trying. You know, and corporate people, first of all, if you're a CEO, you've got six years career at this organization, and then you're very seldom that a corporate CEO, who's a hired gun after all, he didn't create what the organization is doing. He owns very, very little of it in stock options. He's not the major stockholder, he gets an enticement, a package that entices him and everything else, and he wants to do well enough that the next corporate stint that he gets into, he's got a better deal in that stint.

Jeffrey Madoff: Exactly.

Dan Sullivan: So corporate people treat their career as the company that they're building. So they're split-minded. They have to do well enough where they are to do better in the next stint. Okay, so they don't really have loyalty. They have loyalty to their career and they don't want this six years to mess up their career. I don't think creative people really come from that perspective.

Jeffrey Madoff: And it's interesting because creative people, especially if you're on the forefront, if you're the writer, if you're the director, if you're the star or something like that, your failures and your successes are public, and anybody can be a critic and develop a following online and all of that. When you are a CEO, you could say that your reviews are the stock market if it's a public company, but the interesting thing is people will talk about the temperamental artist or whatever, but they won't talk about the CEO ‘till years later. It's not something that follows them from their last stint.

Dan Sullivan: I think it's sad until it's forgotten. That's right.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. Which is really interesting when you think about that. I'll take that. Yeah. So I think that's a really interesting aspect also, because one, you're dealing with, I mean, in both cases, there are certain psychological needs.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. I just think they are different creatures.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. But that differential is interesting because if it's recognized, like I look at Brian Glazer and Ron Howard, they have a terrific partnership that seems to be totally synergistic in creating movies that people want to see. There's nothing that they do that's terribly innovative But it's wonderfully entertaining. But it's popular.

Dan Sullivan: That's right.

Dan Sullivan: So that mutual facilitation, which I think is a rare partnership, but it works. I think it works really well.

Dan Sullivan: And Sam Goldwyn, somebody complained that his movies didn't have messages. And he says, I go to Western Union if I want to send a message. I'm in the entertainment business. They're in the entertainment business. It's like your comment about Kodak. Kodak not understanding what business they're in. They think they're in the film business, actual film, and everything to process film. They're in the memories business. The railroads thought they were in the railroad business and the airlines knew they were in the transportation business. They're not in the airline business. They're getting people from here to there, getting stuff from here to there. But railroads have such huge upfront capital costs that you can get very, very confused to what business you're in.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. If the airplane had been invented first, would railroads exist?

Dan Sullivan: All right, well, this has been a marvelous example of Anything and Everything. What I love is I'll bring up a topic, and you know somebody central, and you've talked to somebody central to the topic, like Marita. You know, when I brought up, or we brought up the topic, I had no idea. And I found that with almost every, you know, somebody who's very central to the topic. And I admired that enormously.

Jeffrey Madoff: And by the way, it's pure happenstance.

Dan Sullivan: Oh, yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: You know, it's interesting because sometimes you don't know who I mean, I didn't know him, but I was in his office with him for an hour and a half with his wife. And the only reason I was in there is because she is a huge fan of fashion. And I was there directing the French collections, which was also weird because I won a blind competition. So they presented fashion work, shows that were shot and edited and all of that. But they didn't give any names. Credit Lyonnais put this together when they were building Forme Lyale, which was this big shopping area. It used to be the fish market in Paris. And so my work was chosen. So I got chosen. Yeah, which was a big deal and there was a significant blowback because I wasn't French. And I was chosen by French judges. So that was kind of interesting. And the time to Morita was because they wanted to distribute the Walkman and Mrs. Morita, who was very into all of that. I was lucky, you know, I couldn't have predicted that, but it was fun. And now I have that story to tell, which is cool.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. All right, see you next time for Anything and Everything.

Jeffrey Madoff: Thanks for joining us today on our show, Anything and Everything. If you enjoyed it, please share it with a friend. For more about me and my work, visit acreativecareer.com and madoffproductions.com. To learn more about Dan and Strategic Coach, visit strategiccoach.com.

Related Content

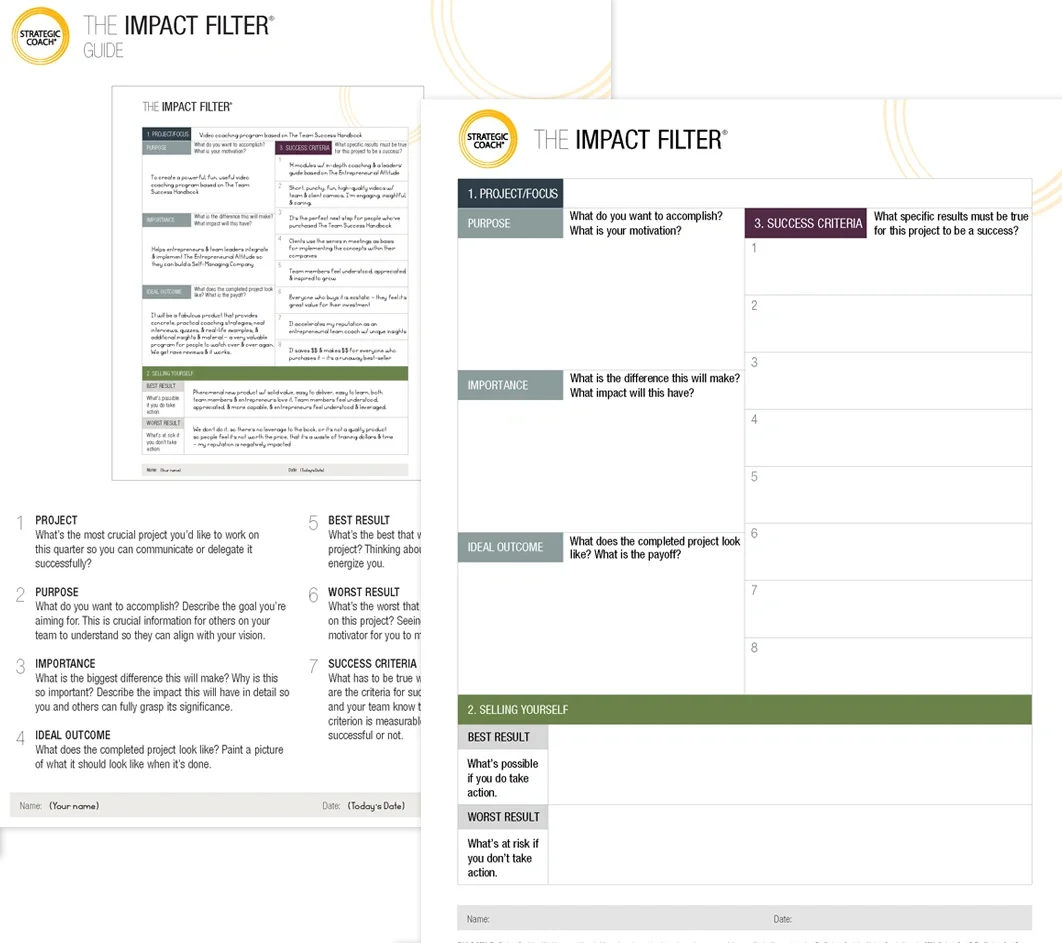

The Impact Filter®

Dan Sullivan’s #1 Thinking Tool

Are you tired of feeling overwhelmed by your goals? The Impact Filter is a powerful planning tool that can help you find clarity and focus. It’s a thinking process that filters out everything except the impact you want to have, and it’s the same tool that Dan Sullivan uses in every meeting.