Breakthroughs And Battle Scars

July 29, 2025

Hosted By

Dan Sullivan

Dan Sullivan

Jeffrey Madoff

Jeffrey Madoff

Do you ever wonder why some entrepreneurs constantly innovate while others stay stuck in the past? Jeffrey Madoff and Dan Sullivan explore how childhood experiences, fear of consequences, and the need for control will either shape or stifle your creativity. Learn how to foster a culture of innovation and why true freedom in business starts with letting go.

Show Notes:

Creativity isn’t something you’re born with. It grows from encouragement, challenges, or even resistance.

Some people are creative because they were supported early on, while others became creative because they weren’t.

Strict childhood rules can create lifelong hesitation about taking risks.

Whether it’s parents, teachers, or bosses, too much control shuts down creativity.

Creative thinkers don’t fear consequences. Everything is feedback.

The best businesses welcome all ideas, knowing not every one needs to be used.

You don’t have to act on every creative idea to benefit from the process.

Great ideas start with simple curiosity and a willingness to explore.

Harsh criticism early in life can make people afraid to share their ideas.

The desire to control has more to do with quashing creativity and innovation than anything else.

The world wasn't created with you in mind. So you're going to have to negotiate.

Resources:

Learn about Jeffrey Madoff

Learn about Strategic Coach®

Do You Know What’s Keeping Your Clients Awake At 3 A.M.?

The 4 C’s Formula by Dan Sullivan

Casting Not Hiring by Dan Sullivan and Jeffrey Madoff

My Plan For Living To 156 by Dan Sullivan

Episode Transcript

Jeffrey Madoff: This is Jeffrey Madoff, and welcome to our podcast called Anything and Everything with my partner, Dan Sullivan.

Dan Sullivan: This one is about entrepreneurism, but it's really about how does innovation actually take place? How does inventiveness actually take place in the entrepreneurial world? And Jeff, is it a particular type of person? Is it a set of conditions? You've been doing this all your life since childhood. So what's your take? Why is it that some people are creative, some people are always coming up with new things, and some people aren't? Well, there's no one reason. That's the first principle.

Jeffrey Madoff: There is no one reason. That's right. And in a way, Dan, this one is almost like a part three of our previous two in terms of also taking this to a personal level in terms of motivation for the entrepreneurs, for you and me, in terms of just sort of understanding these things on a different kind of a level. I think that there are people that are creative because their creativity was encouraged when they were young. I think that there are people that are creative because their creativity wasn't encouraged because they were young.

Dan Sullivan: It's actually prohibited. That pretty well covers anything and everything.

Jeffrey Madoff: . Exactly, exactly. So, you know, I think that in a business setting, the way to foster creativity is to welcome it. Doesn't mean you have to adopt it. It doesn't mean you have to adopt the innovation, but a lot of people don't realize the difference between the process of it and, you know, you can embrace the process, which I think is really important because that's where innovation and creativity come from. But that doesn't mean you have to necessarily implement it or it's right for your particular business circumstance.

So we all like to get praised for what we do, even if we deny that. It's kind of a human instinct that we want acknowledgement for what we do. And if what you do is in those creative areas, I think that that makes you want to do it more. Or if it satisfies something because you've been shut down on doing that and you've somehow liberated yourself, if you will, to take that expression despite the obstacles, you can be quite creative on that also. So, like most things, there's no one thing.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, you think you're born with this instinct and that it can be suppressed so it doesn't go anywhere, but if you have sort of a, and I'm gonna use the concept of freedom here—you have a certain amount of freedom from adult supervision. You have a certain amount of freedom from your parents' expectations of who you are going to be. But you're doing something different with your experience. Right from the beginning, you're doing something different with your experience that what's going on inside your head is as interesting to you as what's going on outside of you.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, I think that early childhood, you're an infant, and hopefully throughout one's life, but there's discovery going on. From discovery, there can be creativity, if that's encouraged, Again, the process of it, I think that that's a fantastic thing for people. If they are shut down, and I think this happens very young, there are people that, across the street from me, when I was in Madison, I was probably 21, and there was this guy and his wife and daughter that lived across the street. This guy was a rigid and destructive influence on his daughter. And I saw that because I saw him hit her. I won't go into all this stuff, but it was awful.

But the thing that stayed with me so much is he said, don't cross that line. There was this line on their driveway. She was allowed to play in this area. Do not cross that or you will be punished. And I would watch this and she would go up, when he went back in house or whatever, she would go up to the line, she would not cross it. And she's probably five, five or six at the most. I said, wow, this is profoundly sad that whatever fire that kid had was doused at such a young age because her father didn't know how to handle it and that anything that wasn't in his grid was punished and shut down.

And by the way, that can also happen with teachers, that can even happen with your peers when you're a little kid, if you're made fun of, things that make you not want to expose yourself to criticism or that kind of pain. But it really hit me, I haven't thought about this for decades, really hit me, I'd sit on my front porch and I would watch her approach and then not go any further. And I thought, wow, I'm seeing her whole life right in that moment. And her father and I had a confrontation. I won't go into that. But it so deeply saddened me to see that, and to me it became, wasn't symbolic, because it actually was a true inhibition on what she was allowed to do. But that image of the little kid approaching a boundary, but being told not to cross it by the parents, and this wasn't anything that would place her in danger, I'm not talking about that.

Dan Sullivan: It would place him in danger.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. Well, his sense of control.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: And I think sense of control is interesting because if you are holding on to something with white knuckles, that kind of a grip, that kind of control, you're right, it placed him in danger, his concept of control, really, and himself. And you're right. And I think it's interesting, probably the desire I won't even say probably, I think the desire to control has more to do with squashing creativity and innovation than anything else. And that can come from parents, teachers, even your peers.

Dan Sullivan: I'm trying to think how I approached that, because I grew up on a farm, and I could do anything I wanted on the farm until I was six years old. But I couldn't go on the highway in front of the house. But it was pretty easy for them to explain why not, because there were trucks barreling along. We live next to, this is west of Cleveland, and they have a lot of sandstone quarries out there. They made slag, you know, for the building, and these trucks would come along at 70, 80 miles an hour because they were paid by the trip. The drivers were paid for each truckload that they could get in. They got paid for the truckload, so you wanted the trip to be as fast as possible. And then there were the fence lines. The fence lines were with the neighbors' farms. And then there was the woods. You couldn't go into the woods.

But at six I could, so I was told, you know, when you're six you can go into the woods, but before that, and I was pretty observant to that. But my father didn't tell me any of this stuff. This was my mother. I was number five, and she already had a lot to contend with, with the first four. So I had 70 acres. You know, they're different fields. There was a swamp. She didn't say anything about the swamp. I could go into the swamp. And I've told this story before on our podcast, but when I was six, I got to go into the woods. And it was great. It was about 10 acres and it was really neat. All sorts of interesting trees and I could climb the trees.

So after my first day, I came running back to the house and I says, mom, mom, guess what I did in the woods? She said, nope, nope. Don't want to know what you do in the woods. The dog's with you, we had a dog, and the dog always went with me. And she says, anything happens, the dog will come back and bark, we'll find you. But I do not want to think about what you're doing in the woods. So on the one hand, I had this sense of restriction, but I also had this sense of freedom that she didn't want to know what I was doing. So that was the freedom part of it.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, and what's interesting, when you said the highway, and of course, it was easy to explain why, so often, like this little girl across the street.

Dan Sullivan: There was no explanation for the line.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, well, the explanation was, because I said so.

Dan Sullivan: Yep, yep, yep.

Jeffrey Madoff: That was the explanation.

Dan Sullivan: Not an interesting topic. Yeah. Very definitely not an interesting topic.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, and to me, hearing because I said so, was reason enough to go counter to it.

Dan Sullivan: You can eat anything in the garden, but do not eat the fruit of the tree of knowledge of good and evil.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right, yes.

Dan Sullivan: It's like an apple to me.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's because they were trying to save it for themselves.

Dan Sullivan: You know, that's a really fundamental story, the garden, because on the one hand, it's depicted that they went against the will of God, you know, and it's always the woman is the one who starts the trouble. But in that moment, free will was created. Psychologically, free will was created.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, if you succumb to temptation.

Dan Sullivan: No, is that you were given an order and you disobeyed the order, which meant that the creature had free will.

Jeffrey Madoff: Or it was setting up a lesson with consequence in that knowledge, because, of course, God knows everything.

Dan Sullivan: Of course, free will has consequences. Let's talk about that a little bit, because I think that the whole question of consequences is an interesting topic because I think creative people approach consequences differently than people who are afraid to go outside of the lines. They are across the line and everything else. There's interesting consequences. I wonder what I can learn from negative consequences. And I think there's something about the creative attitude. The person who's creative is willing to just have an experience that's new, different, and possibly better than the experiences that other people are having. Yeah, and I don't know when you're a kid that you could even articulate that. Well, I'll give you an example from your own life, writing a Broadway play after you're 70 years old or close to 70 when you started it. Did people tell you about the consequences?

Jeffrey Madoff: They just wondered why I would even do it. You know, why would I even do it? And, you know, it's funny because I think it's pretty much true that my close friends, there's not one of them—not one that did anything other than say, well, that's really cool. That's great. You know, and those were my close friends. Other adults that I know, you know, was, why would you want to do that at your age? Why would you want to undertake something like that? You know, that sort of thing.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Well, what's that mean at your age? So what does at your age, what kind of thought is that? I mean, to look at it from how they're seeing, what does at your age mean? What does that mean? This is not possible. If I were to do something like that, you know, I would be a failure.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, yeah, I think most people when they say things like that, are talking about how they live their life. And we're doing something that is different and that can be threatening.

Dan Sullivan: Again, not an interesting topic.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. Well, you know, I remember when my dad turned 40. There was a birthday party at our house and my dad was very athletic, very good. And he played tennis and loved playing tennis. I remember this so vividly because so many people said, now, Ralph, now that you're turned 40, you gotta stop running around on the tennis court like you're a teenager. You're gonna drop dead of a heart attack. And my dad, who was fit and always had younger friends, he just brushed it off and didn't even bother responding to it. But even as a kid, I was 10 years old, and I'm looking at this fat guy say to my dad, what are you running around on the tennis court for? And I thought, you can't do it. You know, you've let yourself go already.

And you know, when we were kids, 40 was deep middle age. Very deep middle age. I mean, that was like, you know, things were kind of winding down, you know, and the first few shovelfuls were being dug for your grave. But my dad didn't even feel compelled to say anything, because that was nothing he was going to debate or argue. He was going to do what he wanted to do. But it hit me at that young age that they were talking more to themselves than they were to my father.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, so I think that on the part of the creative person is that how other people live their lives may be interesting information, but it's not central to you. How you're living your life is what's central to you. I've spoken about going home to family reunions and not one of my siblings—I have five living siblings. There was a sixth one, he's dead. They're in their seventies and eighties. One is going to be 90 in June. And not once in 50 years has anyone asked me what I do for a living. But I put out an offer that if any of their grandchildren wanted to go to university, I would pay for half the tuition. And I've done 12 so far. Actually, I'm in London in the next two weeks, and my grandniece lives in London. And she always wants to get together when I come in. Part of the reason is that I finance part of her education.

But the thing is, why she likes talking to me, she says, you're the one that got away, aren't you? And she wants to know how it was that I got away. And I said, you know, I wasn't trying to get away. I just had something next in terms of what I was really interested in that required me to be somewhere else. So it's not a freedom from, it's a freedom to. And I think the big difference between creative and non-creative people, I think people all want freedom, but one of them has a negative freedom that it's a rebellion against something that they want to be away from it. Okay, but it doesn't matter how successful they are, it doesn't matter how long they live, they're always relating it back to what they were trying to get away from. Whereas the freedom of to is that you just created something and it's really neat, and you see possibilities of expanding the really neat feeling.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, it's like the line in the Brando movie, The Wild Ones, about the motorcycle gang. And somebody says to him, what are you rebelling against? What do you got? You know, but it's interesting because for her to ask you that question of how did you get out speaks volumes. Number one, she feels imprisoned.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, she does.

Jeffrey Madoff: And number two, that she sees you as somehow able to navigate and escape. And at least she thinks she'd like to do it. She may be too cowed and beaten down at this point to ever do it, but she recognizes. that, which is, I think it's probably true that in some cases, many cases, ignorance is bliss. Because if you have given up that fight for your freedom, you know, psychologically, emotionally, I think there's a pain that goes along with that, you know, that can lead to other things.

Dan Sullivan: There's another aspect to that. There's pain avoidance, and that's one approach. You're trying to avoid pain. But on the other hand, there's a saying, well, maybe pain is the price. In other words, you have a sense of trade-offs, that if you're gonna do one thing, there's gonna be a trade-off. But it's a question of whether you have a backward reference, you're getting away from, or you have a forward reference, there's something bigger I see and I'd like to get to it.

Jeffrey Madoff: And I wonder, how does that manifest if a person who is getting away from something—I mean, like Lloyd Price was getting away from something. But I have to say, in the years that we were together and became very close, I never saw any bitterness in him.

Dan Sullivan: No, me either. And you didn't reflect any bitterness.

Jeffrey Madoff: No, I mean, certainly the play doesn't. So it's kind of interesting because it also is how that person deals with their lives, because if they're in a leadership position in business, they can be the worst kind of people to be around if they have that kind of bitterness, because they're also oftentimes likely to shut down somebody else because they've been shut down. You know, I mean, there's all these reciprocities that go on to make up for things that happen. I mean, we're all acting out all the time in terms of how we behave, why we behave, and so on.

Dan Sullivan: Oh yeah, no question.

Jeffrey Madoff: I mean, it's really interesting. And I learned, I learned it later in life. It wasn't an early insight of mine that oftentimes when people will ask you a question, it's like, I would be doing reconnaissance during intermission of the play because I wanted to overhear how people were talking about it during the intermission. I was in the bathroom.

Dan Sullivan: Just pick a stall.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. And well, it wasn't a stall, it was a urinal. Somebody said, what'd you think of the play so far? And he didn't know who I was. I said, what'd you think? And then he just uncorked about, you know, his thoughts on the play and all that sort of thing. And I knew him asking me the question. He wanted to tell me what he thought. He wasn't really interested in what I thought about it. And a lot of times it's taking that pause and just listening to what that person has to say. What was your feeling when, I guess it was your grandniece, said to you, how'd you get out? How did that feel to you?

Dan Sullivan: Well, I think one thing is that it meant something very, very different. I mean, I think the big thing is that it was going to be hard to tell her. I said, the big thing is the, you know, it's kind of like where you've come from is very secondary to where you're going. And I think that's the biggest thing. I had this incident. I was out walking in the fields. It was one of those really crisp sort of February, northern Ohio Februaries, but it was getting near sunset and a DC-6 came across from the east, probably from Cleveland or it was from New York, you know, going to Chicago.

I looked up there and all of a sudden I just got this thought, gee, I wonder how far I can go. And that is really the dominant thought, is that once I've done one thing, the question comes back to me, that's really interesting, now I wonder how far I can go. So, how do you explain that to someone else if they don't have that experience? In other words, it's not a negative feeling at all. It's, I've come this far, but now I have the ability to see further. And now I wonder how far I can go with the next thought. Because of what you've been exposed to.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, yeah. But when she asked you that question, I'm just curious, how did that question hit you coming from her?

Dan Sullivan: Actually, I thought it was pretty cool. I said, oh, I've developed a legendary reputation.

Jeffrey Madoff: Dan [inaudible] Sullivan.

Dan Sullivan: Yes. No, I mean, first of all, I took her seriously. She really wanted to know. But the other thing was that her mother, who is a niece of mine, her husband, nephew-in-law, or whatever you call them, they're kind of tightly bound people. I think that there's some kind of lifetime barriers that they've been dealing with, and I think they sort of passed that on to her. They had some sort of line that they didn't want her to cross, I guess, you know, something like that. You know, but different age. I mean, I much prefer growing up in the 1950s than growing up in the 2020s.

Jeffrey Madoff: How old is she? College age?

Dan Sullivan: Oh, no, she's way beyond that. She's in her forties. She's the oldest of that generation. There's about 20 at that level from that generation, big span, you know, big age span from first person to the last person in the generation. But there's just a uniqueness about every human life. One good concept to come to grips with when you're born and born into this world and you're growing up, one good thing is none of this was created for your purposes. The world was not created with you in mind. And I think that gives you a tremendous amount of freedom, therefore, you can more or less do what you wanna do.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, and how you described your answer, or how you felt, I think is really key in relationships, business and personal, which is, you said, you took her seriously. And most people never feel that they've been taken seriously, that anybody actually cares about what they think or feel or anything else. I had a friend who had a frightening temper which had never been exhibited to me. And then we were in a restaurant, and after we ate, we're walking out. I'd never seen this aspect of him.

We're walking out, and he deliberately leans and bumps into a guy sitting there. And he stops. And Dave was an imposing guy. He's like 6'3", and said, you bumped into me. And the guy said, sorry, I was just sitting here. I think you bumped into me, but sorry. And he goes, that's not enough. And I'm thinking, uh-uh. And I saw, you know, primate jaw unlock, and I said, come on, let's go, man. And he goes, no, just a minute. And I said, David, let's go. And I got him to leave, and the other guy didn't know what the fuck was going on.

Dan Sullivan: Still doesn't.

Jeffrey Madoff: Hey, that's right. We got back to his apartment, and I said, what was that about? He goes, what was what about? I said, you were willing to get into a fight, you bumped into the guy, you know that. Why'd you do that? Why were you so ready to get into a fight with this guy? And you're the one that lit the fuse. And his whole expression changed. And he said, you know, my dad used to beat the shit out of me. And by the time I was 17, I was his size, and he would smack me, and I would not give him the satisfaction of knowing it hurt. I said, so what does that mean, what did you do? He said, I just looked at him, and in my mind, it's, you're not gonna hurt me. And his dad, from slapping, closed his fist and punched, and I said, what did your mother do during that? Because, you know, this would never happen in our household. If it did, I would be dead on the floor, because Margaret would kill me instantly.

And nobody had ever asked him before why he was triggered. And very smart guy, very interesting guy, and when he was telling me that story, it was like so alien to me because nothing that would ever happen like that in my house, in my parents' house. But it made me understand, it was almost this cascading effect that I understood, not only people I knew, but I could recognize the behavior of people who had been abused. I knew somebody that would pick fights, but only with groups of people so he'd know he'd get the crap beat out of them. Because he had to be punished if he did that. And I think that, you know, this circles back to, talk about the theater of life. Well, where does all the great work come from life?

Dan Sullivan: Right. I mean, there's very definitely a plot there. There's a role there. Have you ever seen the movie The Great Santini?

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I think I did a long time ago. Robert Duvall and, you know, how he bullied his kid. I mean, they'd be playing basketball in the driveway. And for his dad, it became a blood sport. It's a very, very good film. But I think that, you know, the genesis of all of our behaviors start quite young.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I think that's true. You know, it's really interesting because I grew up Catholic and the not original Bible is the Bible that we grew up with and everything like that. And in the Bible, Christ never talks about doing anything bad to other people. You know, there's no mention except for one thing, those who scandalize children should have a millstone tied around their neck and thrown into the sea. Well, someone who brutalizes their children is scandalizing their children.

Jeffrey Madoff: No, absolutely.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. I just wonder, a lot of addiction, I think, really comes from that you are either done to, and that memory has hardwired your brain, it's hardwired your nervous system, or you're the person who did it. I mean, it's hard to know the chicken and the egg here. Because I had really, really, by anybody's definition, I had very, very gentle parents. Yeah, but my father's father was a brute, and he responded by going in the other direction. You know, there was no violence whatsoever in our setup, and I think that's important. I don't think the child brain knows how to deal with violence. I don't think you can think it through.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, and I also think that you don't want to have it taught to you. This is how you resolve differences. You know? Yeah, I mean, it's really interesting because, yeah, I mean, the world is a stage and we play out our emotions on that. It's very poignant when someone says to you, in this case, you, how'd you get out? Because family and prison were synonymous in that situation for her. And it's interesting because one of two things often happens, either that kind of conversation happens and you're the person she looked forward to at any of these family reunions, to seeing and talking, or there's an embarrassment that they expose themselves because they don't know the response to that exposure and they're embarrassed by it, so they don't revisit. Did she fall into either of those categories?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, my sense is her life is hard work.

Jeffrey Madoff: So let's get to business, okay? And how do you integrate creativity, artistic expression into what you do? And do you view that as being essential or is that just supplementary?

Dan Sullivan: No, it's the center of the business. The question is how do you structure a business and have a good business which allows for the possibility of constant creativity. So I started the other way around. My sense is that one of our advantages in the marketplace is that we're the coaching company that's always creating new stuff. We don't have a cookie cutter that was established 30 years ago and it's how many cookies can we make and sell that aren't new cookies? One of the interesting educational structures that I had was working for the ad agency, BBDO. I worked for the Canadian headquarters of BBDO, you know, big global agency, but in Canada, number two, you know, big clients, world brand clients, Chrysler, Kodak, neither of which presently exist in any meaningful form as they did back then.

But one was the rule that what you did yesterday doesn't really matter. What are you going to do today? And I had three years of that and that was a terrific training as long as it didn't become four years. I needed that three-year experience where, you know, what are you doing today? You got to create new stuff today. That was a tremendous education. I mean, because I had just come out of a college which studies the great books of the Western world, where if it was great in the last hundred years, it doesn't really matter, you have to go back 2,500 years. And it was a nice balance because there's some things that are permanent, and it's good that they're permanent, and there's some things that need to constantly be created new. And I believe that all creativity is something new. I mean, it's new, it's different. The question is, is it better?

Jeffrey Madoff: Bill Persky, a friend of mine, he was a producer of The Dick Van Dyke Show and That Girl and multiple Emmy Award winning writer and director and producer. We were talking about the writer's room, what would go on in there. And he said, you know, at a certain point, you're not making something better, you're just doing it different. And that was a collaborative situation, but nobody could make a final decision on something. And, you know, how important is collaboration in coaching?

Dan Sullivan: You know, I'm going to see my grandniece in a couple of weeks.

Jeffrey Madoff: The one we're talking about?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, the one we're talking about. And I said that first principle, you got to come to grips with that the world wasn't created with you in mind. So you're going to have to negotiate. If you want some space and you want some freedom and you want some movement and progress, you're going to have to do it through negotiation with the world. Okay. But the big thing is, you know, there's an enormous amount of freedom in realizing that none of this is really about you. Yeah, what really makes it interesting is that it's about something outside of yourself that you can respond to, you know, and you can learn and you can grow in capability and you can produce achievable results and everything like that. And that's constant. It only stops when you say it stops

Jeffrey Madoff: . So, two things. One is, How do you, in a coaching situation, and what you do, how do you foster a great collaboration?

Dan Sullivan: When I first did it, the first 15 years, it was one-on-one, you know, like I just had single clients. So the big thing was to get them into their own brain so that they can start talking about how they're actually seeing things, past, present, and future. You know, what's it look like to you? And then where you can see that they've run into walls or they've run into uncertainty or anything, just ask them, well, what do you really want? What do you really want there to happen? And they said, well, I really want, but I said, well, let's forget the but part of the story. Let's just really get clear about the thing that you're working on if we move it into the future.

And the big thing is that the creativity really has a great deal of freedom in relationship to what you think is the past, what you think the present is, and what you think the future is. Because a lot of people, the future is rigid. A lot of people. To the degree that you think your past is rigid, your present and your future is also rigid. You can do anything you want with your past. Nobody else knows anything about your experience except what you tell them. They can watch you for five years and they can't say what your experience of those five years were from the outside. So the big thing is to get the person back inside themselves as a coach and say, what do you really want?

Okay. And they'd say, well, I need, I said, no, no, it's not about need. We all sort of need similar things, but what we want is radically different. So let's just talk about want. Well, this is what I would do. I say, well, let's put you three years ahead. How are you operating differently three years from now than you're operating now? That makes you feel good. I mean, it really excites you. And pretty soon it comes down to some pretty measurable results. Shows up in revenue, shows up in, you know, how they're using their time, has to do with who they're dealing with, has to do with what kind of support they have around them. And I get them to write these down and put numbers to them. Numbers are really important. Numbers are really important. The human brain really loves numbers, you know, and if you can put a number to something, it's the difference between moral support and actually a check. Yeah, moral support feels good in the moment, but a check feels good in the future. The check creates a different future.

Then I'll say, you know, well, let's just focus on one of these. What are the obstacles that you have right now? Okay, and then I'll say, what have you already done in your past that's kind of similar to this? You were successful in overcoming it. And all of a sudden, they're starting to use their past as a repository of usable tools. And I say it like that. And then you put a deadline on it, and I find you never want to push it too much more than 90 days. But then there's decisions that have to be made, some communication that has to take place, action has to take place. But the big thing is teamwork. They're gonna need teamwork. They're approaching the future as a lone individual, okay? And you gotta show them that there's a lot of help out there if they can do it, you know, so. And to not be afraid to ask for it, you know. And that's where the collision, are they seeking freedom from or are they seeking freedom to, because freedom from, there's no help whatsoever. It's just you against your past. Freedom to, there's all the help in the world if you can get them interested in your project.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right, right. Interesting, pretty profound distinction there.

Dan Sullivan: That's why I think people who are feeling very isolated, very alone, alienated, it's them against their past and it's not an equal fight.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right. No, because you don't win that without a lot of help.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. First of all, nobody back there even remembers that or even cares.

Jeffrey Madoff: So, you know, collaboration, we both agree, is really important, can be really fruitful. I think it boils down to when you're talking about your grandniece, taking her seriously. People want to be taken seriously. They want to be heard. But then at a certain point, a decision has to be made. And action has to be taken. Otherwise, it was a lot of talk. No action, no change. So that to me comes down to then leadership. So what would you say are the qualities of a great leader?

Dan Sullivan: I think all leadership starts on the individual level in the sense that there's a new capability that you would like to have. So, for example, the two of us are collaborating on a project where there's a new capability that we're creating, a book called Casting Not Hiring, that's bringing together an enormous amount of wisdom that already exists in the business world, that casting people in a team is much superior to hiring people for individual roles inside an organization. You know, it's a fundamental mind shift. And what's interesting and gratifying is that all the interviews that you've done, you know, you've done a lot, right now, these people who are telling you things may never have said the things that they said before. And it has to do a lot with your interviewing capabilities, but we actually created a little book to get a big book.

Okay, so we created a little book, and then we could send them the little book. That was a capability. And the importance of the little book was it allowed you to have a conversation where the person could really think about how do they look at this before you actually talk to them. And so my definition of leadership is where any person decides they're going to create a new personal capability that requires them to be committed, requires them to go through a period of courage. I prefer short courage to long courage. Then they get a new capability and then their confidence jumps and they're witnessed by other people doing this. They're witnessed. And the moment that witness, that person is a leader, they're doing something because every individual is confronted with a daily challenge. What new capability do I want to develop, achieve that makes me more confident, expands my possibilities?

And this is very different from leadership when we were growing up in the 40s, 50s, 60s, that the way things had been organized in society mostly was pyramidical. Goodyear, Firestone were big pyramids, you know, you were living in Akron. We were living where the three big automakers, Ford was here, GM was here, Chrysler was here, steel mills were in Lorraine in Cleveland. But those were huge pyramid organizations. You know, the whole Great Depression had been about the big pyramid of government forming in Washington that provided all sorts of programs to people. Second World War was a big pyramid where everything was disowned. And so, you know, your whole notion of what life was going to be was finding your place in the pyramid and then mainly moving upward.

And that all fell apart for a lot of different reasons, but the big one is the microchip. The microchip comes along and says, no, no, no, no, that's not how it works. I'm saying what we've learned from 50 years of the microchip here, it's networks. How many different connections can you make? Because we've got the electronic tools that allow you to make all sorts of connections. Okay. And it's harder to work out what leadership is there, except if you bring it back to the individual. And the individual, I'm going to develop a new capability, okay. And all of a sudden, everybody's really keenly interested. How is he doing this? How is she doing this? And the person develops a new capability. They say, wow, we can do that. We can do that. So I think there's been a profound change in what constitutes leadership over the last 50 years. And when you're talking about developing a new capability …

Jeffrey Madoff: Wrapped up in that package is also risk.

Dan Sullivan: Yep, very much.

Jeffrey Madoff: So how do you evaluate whether a risk is worth taking and what criteria guides your decision making?

Dan Sullivan: I think the biggest risk is how you were doing it before is going to become obsolete. And that's a big risk for a lot of people. You're putting your past at risk. If you want a different future, you got to put your past at risk.

Jeffrey Madoff: Explain that a bit more.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Well, this is the way we always did it.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Well, I want something new, but we got to do it the way we've always done it. Well, the creativity game doesn't work that way. It's a different game, you know, like, it's very, very clear. I did an AI search yesterday and I said, to what degree can the types of work that bureaucratic employees and bureaucratic managers and executives, to what degree, given that this is the type of work they do, how much of that work that they're doing is in danger of being made obsolete by what AI does? And it's about 90%.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, that's maybe Marc Andreessen was recently.

Dan Sullivan: Marc Andreessen, yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah.

Dan Sullivan: Very smart. Very smart guy.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. I don't know that anybody particularly has a spotless record in terms of forecasting the future. And the future never comes because it's always tomorrow. You know, like singularity.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. When tomorrow is today, you hope it was better than yesterday.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes. And don't know what tomorrow will bring. Yeah.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. And you know, the neat thing about what you just said is you got to be okay with that.

Jeffrey Madoff: What do you mean?

Dan Sullivan: Well, you can't go on autopilot.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right.

Dan Sullivan: You're always going to have to wake up and say, from a certain standpoint, okay, it's back to square one again. What am I going to do with today? Certain people run out of the energy for doing that. They run out of reason for doing that.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, well, I think when you run out of reason, then you run out of energy because you don't want to do it anymore.

Dan Sullivan: Let's go back to the conversation of acquaintances that you had regarding your plans to create a Broadway play, you know, at what they consider an advanced age. You obviously have a reason for doing that, and it's not a reason that they can comprehend.

Jeffrey Madoff: Or frankly, that I care whether they do or not.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, and that's a big win because they would care what other people thought.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right. There's definitely times where other opinions matter and that I take heed of that. But when I'm being questioned or warned about something, if someone has a sincere question, I don't mind answering it. If somebody's question isn't really a question, it's more expressed …

Dan Sullivan: It's actually a judgment.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes, exactly.

Dan Sullivan: It's actually a judgment, yeah. I mean, if someone said to you, I mean, the way I would, because we were at lunch when you told us about it, and both Babs and I were thrilled about what …

Jeffrey Madoff: You guys have been wonderfully supportive both emotionally and financially.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, what a neat thing. What a neat thing. Yeah, but you know, there are people who are at 70 who are young and people at 20 who are old.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right.

Dan Sullivan: It's actually conceptual. They just don't have anything in their brain beyond where they are.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I guess it cuts two ways with me. On one hand, I don't disregard anybody unless It's just getting a face full of their judgments, which I'm not interested in.

Dan Sullivan: Not an interesting topic.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. Yeah. What's interesting is the vigorous exchange of ideas and even the differences that those points of view bring about and trying to understand those differences. I mean, I think one of the most terrible things that has happened in recent history is not only are we divided, a significant number of the population don't feel like they can even talk to each other anymore. And that's tragic.

Dan Sullivan: You know, in American history, this is not unique.

Jeffrey Madoff: I know. It's a contentious society.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, yeah. Well, look how it came about. The period that we were born into was a unique period of human history, U.S. history, but I think actually human history where you had a standoff between two superpowers and the consequences of a war between those two put every other issue in a secondary light. Okay, you did the atom bomb exercises in school and so did I. You know, you had to make sure you were totally underneath your desk or, you know, you were going to get it. Well, no, you were just going to be vaporized. I mean, nope, nope. And they couldn't find the dust afterwards. And I think that that really, really changed consciousness.

I think that notion—it's like we have no flying cars. We've had viable flying cars since 1947. Somebody had a really doable flying car in 1947, and we're still without flying cars. And I said, the reason is that, just from a probability standpoint, if you're in an accident and you're on the ground, there's a chance that you could walk away from it. You have an accident at 1,000 feet, nobody walks away from it. I mean, we immediately see what's the worst-case scenario with anything new. And you say, you know, run out of gas, run out of electricity at 1,000 feet, and there's only one outcome to this. And that's why. And the other thing is we don't like things flying over us that'll drop and hit us, you know.

People have said, well, they're going to have drone deliveries now, you know, and I'm pretty forward thinking in terms of technology. You know, Amazon will have drones that drop in your backyard, you know, and deliver a thing. And I said, I'd vote against it. I don't want things flying over. I don't want the noise. I don't want the possibility they drop the package. I don't want the fact that criminals will know about this and they'll come right to my neighborhood and steal it. So the big thing is they think that the people who are opposed to this are being irrational. You know, you're being retrograde. And I said, no, we have some experience what height means. We have some experience what things dropped on us mean and everything like that.

And I said, you got to take that into account. Take everything that people are worried about and safeguard the person against that so that it doesn't happen. But back to the creativity part of it is that, I mean, the first thing that we go after in Strategic Coach is how long does the person expect to live, you know? And we have an exercise called The Lifetime Extender and most people have a number without knowing they have a number. It's family history, it's actuarial tables, it's, you know, just observing people around them. My sense is with the person having a purpose and having what I would say ready access to medical and technological breakthroughs today that probably you can get to a hundred really, really good. I think most people can get to a hundred.

There's no evidence whatsoever that overall we're living longer. We do have a lot of evidence that a lot more people are living longer than they used to. Okay, but there's some codes that they haven't cracked yet, and one of them is, you know, if you're 100, how many other hundred-year-olds do you have to hang out with? Not that many. And community is really the biggest issue for life extension. How much of a sense of community do you have? Meaningful community. Friendships, yes. Friendships and exciting projects. If you have an exciting project at 100 years old, you're rare.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I think sometimes the exciting project is just staying alive, you know. But I think I've got a part four for this percolating.

Dan Sullivan: But this has been—number three doesn't end until you have number four.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. Rule.

Dan Sullivan: This is a rule, yeah. But my sense is that, I just want to say what I got out of this, is how much important what your brain does with time. What does your brain do with the past? What does your brain do with the present? And I think all humans are completely unique with this. I don't think there's much overlap where people do that. And is time something you can work with or is time rigid?

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I think back to when prior to the railroads, there was no such thing as standard time. There were literally hundreds and hundreds of time zones in the United States, and it was the clock in the town center. And that was kind of it. It wasn't synced with anything else.

Dan Sullivan: And it didn't have to be because there was no possibility of accidents.

Jeffrey Madoff: And so what was fascinating is in organizing and systematizing time, the effects that that has had and still has, even to the point that the drone delivery of Amazon, where you can get things within three hours. Now, first of all, I can walk into a store and walk out with it instantaneously. People tend to forget, oh, look how innovative this is. I can walk in and walk out with what I wanted to buy.

Dan Sullivan: New idea, pass it on.

Jeffrey Madoff: And then we could have trucks instead of horses do delivery. I mean, you know, but so much of what the internet has done is the expectation of immediate gratification and speed, neither of which is necessarily better. But it's a business opportunity. So I find that fascinating, but I also find, you know, fascinating the interpersonal aspects that we talked about too, what shapes us, and even the impression, impact, and in the best circumstances, positive inspiration we might have on others that we're totally unaware of.

I mean, I've had people approach me and say, you know, when I heard you speak three years ago, I went, what? You know, because at that time in their life, what they heard, tremendous resonance. Because we're all people. You know, we're all dealing with varying degrees of things. I just find it all so fascinating. And to me, it's like every day learning something. And that observation, as I'm writing this play or writing our book, the new discoveries that are made that lead to other ideas that I want to amplify.

Dan Sullivan: Well, I'll tell you, whatever temptations I've had to start fights in restaurants, the days are over. I've only had that urge when I got the phone. Careful, think badly of me. Don't do that. I mentioned that I thought that, you know, with my grandniece, I thought it's a hard job, but for all of us, it's a full-time job.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right.

Dan Sullivan: Life is a full-time job.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right, that's right.

Jeffrey Madoff: So we were pretty much within the boundaries of anything and everything.

Dan Sullivan: Oh yeah, we didn't wander too much.

Jeffrey Madoff: No. But, you know, you change the A in wander to an O and you've got wonder. And I think we're usually traveling between those two places, which are good. That's a good place to go.

Dan Sullivan: And they're necessary to each other.

Jeffrey Madoff: They are. They are. Thanks for joining us today on our show, Anything and Everything. If you enjoyed it, please share it with a friend. For more about me and my work, visit acreativecareer.com and madoffproductions.com. To learn more about Dan and Strategic Coach, visit strategiccoach.com.

Related Content

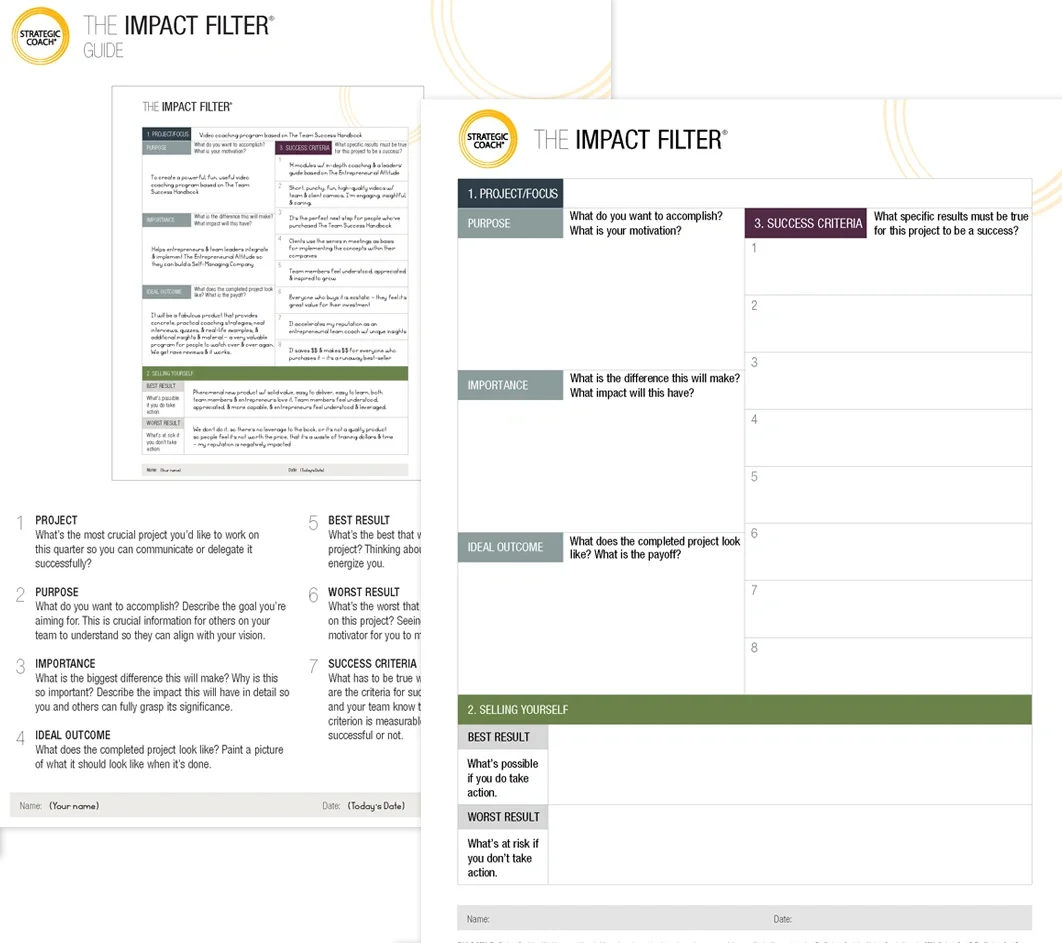

The Impact Filter®

Dan Sullivan’s #1 Thinking Tool

Are you tired of feeling overwhelmed by your goals? The Impact Filter is a powerful planning tool that can help you find clarity and focus. It’s a thinking process that filters out everything except the impact you want to have, and it’s the same tool that Dan Sullivan uses in every meeting.